What IS in a name? Rather a lot, as it happens.

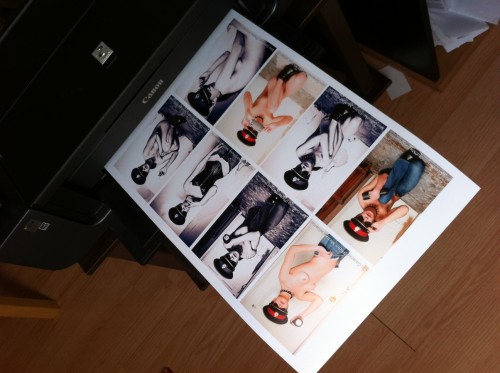

Take the company formerly known as Artisan State. They do great albums and other print-related items. I cannot recommend them highly enough.

Except, that is, for their current name. It is now “Zno“, which every world citizen except an American pronounces as the monosyllabic Russian-sounding “zno”, Vaguely sounding like “snow”.

But the company thinks it should be pronounced as “Zeeno”. Because while the entire world calls the letter Z “zed”, since it is derived from the Greek zeta, Americans, and only Americans, call it “zee”.

And so, apparently, should we.

Except some of us—meaning me—feel rather strongly about language, and while I’ll gladly let Americans pronounce Z as “zee”, or “zoo”, or “za”, or “zeeblebrox”, or anything else they like, I just cannot get myself to do it. Z is zed, not zee.

But of course there is a bigger thing behind this. Namely American exceptionalism and ignorance of the world, and even, if you like, cultural imperialism. Much as I love my American friends, I think they should perhaps educate themselves just a little bit, and realise that the entire world is not America. And something as crucially important as a brand name… why on earth would you choose something that either puzzles or antagonizes the rest of the world? Unless, of course, you only want to sell in America.

So we have problems. Until I live in the USA, I do not want to start pronouncing Z as “zee”, even by stealth, and I do not want to buy from a company that is at the very least either ignorant or culturally insensitive at its senior levels. When I have pointed this out to the company’s support email, all I got was a “we think of it differently”, or some such non sequitur.

So just like I would find it difficult to respect a president who is a racist and a mysogenist (and I am not pointing at Mr Trump here: I suspect he is a lot more intelligent than we think), I also find it difficult to buy from a company that is either ignorant or is trying to push American culture down my throat.

So yes, there is a lot in a name. A name is culture and language, and people care about culture and language.

Am I making a big deal of this? Nah. No big deal. I can buy albums, even good albums, elsewhere. I can recommend other print companies to my students. No skin off my nose.

But I do wonder why a company chooses not to care about antagonizing a great proportion of their market. Are they ignorant, or do they want to push American culture down the world’s throat? I’d say both are equally likely.