What one person finds complicated, another finds simple.

And vice versa. A friend who visited the other night reminded me of this, when I talked about the simple four-flash light setup I was using for a headshot:

And as he said that, I realized that perhaps it’s not simple.

But if you want to take portraits, then it should be. In other words, without knowing how to do a “traditional” portrait setup, it is hard to do creative portraits. No, that does not mean you need to make all portraits traditional – you can do great stuff with one off-camera speedlight and a grid.

But you need to know how a traditional portrait is made. Which is with:

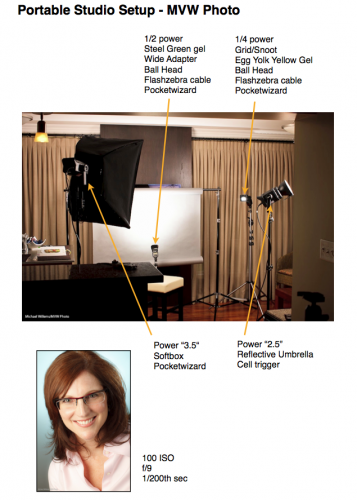

- A backdrop (paper roll, here).

- A main, or “key” light, in this case a Bowens strobe with a softbox.

- A fill light (Bowens strobe with umbrella, in this case).

- A hair light (speedlight with Honl Photo grid and egg yolk yellow gel).

- A background light (speedlight with Honl Photo blue-green gel).

- A way to drive them: Here, I used one strobe and two speedlights fired by pocketwizards; one strobe by the light-sensitive cell.

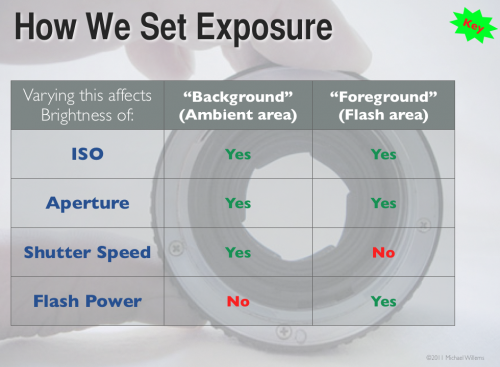

- Metering: I used light meter to arrive at f/9.0 at 100 ISO and 1/200th second.

- Ratios: I set the fill two stops darker than the key. And the hair and background light by trial and error (I got them right first time – done it before).

A note about those gels: colour makes a difference. I love the blue-green gel on the background, to contrast with the red hair – contrast is good. That’s why the butcher uses green plastic between the red meat – to make it look redder. (Oh wait – butcher? We buy meat at the supermarket now, in neat little packages. Dumb me.)

Anyhow – parsing makes things simpler. If you are faced with a complex situation, parse it, i.e. take it apart, one thing at a time. Analyse each layer until you understand it, then go on to the next layer. And before you know it, you will be saying “that’s simple”.

That’s what you learn when I teach you: how to make complex situations simple by understanding the elements, then building on those. Deductive learning, if you will.

And what does the setup above produce? Portraits like this:

(Canon 7D at f/9.0, 1/200th sec, 100 ISO)

A plug, if I may: if you, too, need an updated headshot, and live in the Greater Toronto Area, do call me. For Facebook, your resume, LinkedIn, or your web site: a good headshot helps, and Headshots Specials are on during the month of September!