You know (if only because I have discussed it before) that you can set your flash to manual or TTL. I thought I would revisit this, and show you some shots I took Wednesday.

Manual means you set the power level; TTL means the camera fires a preflash and measures the return, and then sets the power level based on that. TTL (Nikon calls its version i-TTL, Canon calls its version e-TTL) is the default setting (the panel on the back of your flash says something like “TTL”).

An on-camera flash

Unlike David Hobby, I tend to use TTL most of the time, not manual.

TTL is a major revolution in camera technology, because it allows you to shoot varying scenes without having to worry about distance. In particular, you can bounce anywhere you like, off a different wall for every shot, and you can use whatever modifiers you like, and not worry about measuring. And you can use “fast flash” to exceed the camera’s flash sync speed – useful on sunny days.

A sample, shot with TTL on Wednesday:

Bartender at a reception, shot using TTL

Indeed as David points out, TTL has drawbacks: the major one being that it’s not perfect. Its measuring is finicky. If you always aimed your viewfinder at an 18% grey surface you would be fine, but the meter is in evaluative mode, and on top of that it has an undocumented bias toward the focus point. All that means that if I focus on a black area I get grey (too bright), and if I focus on a white area I also get grey (too dark). So I need to use flash exposure compensation. And check the back of the display frequently.

TTL’s pluses, then, are:

- You can use it anywhere, any time.

- You do not need to meter or set anything.

- You can do it when the subject varies.

- You can bounce off varying surfaces, like when you shoot an event and both you and the subjects are constantly moving around.

- You can exceed your camera’s flash sync speed by using “fast flash” (“auto FP flash”in Nikon terms)

- You can use any modifiers you like

And its minuses:

- It can be infuriatingly inconsistent.

- Your subject’s brightness makes a difference.

- Reflections can spoil a picture by underexposing it.

- You’ll need to do more post-production work, as in a fast-moving event, where the setup changes with each shot, quite a few images will be half a stop under or over.

- You’ll even miss a few images.

So TTL is great when things are predictable, but it is also very useful when things are not predictable (like when you, and they, move).

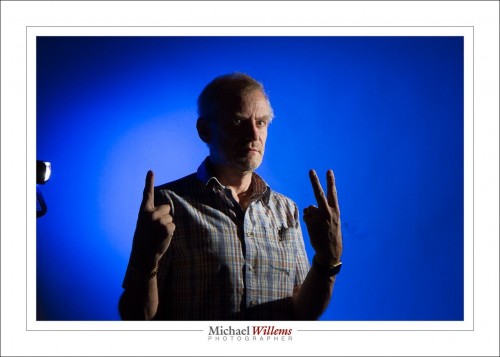

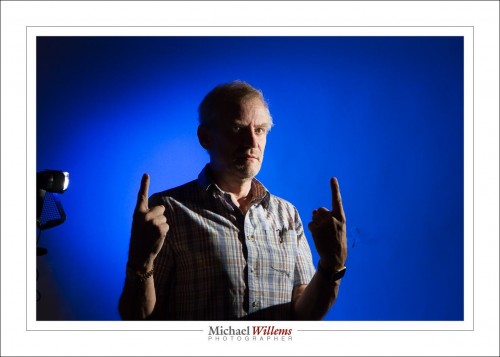

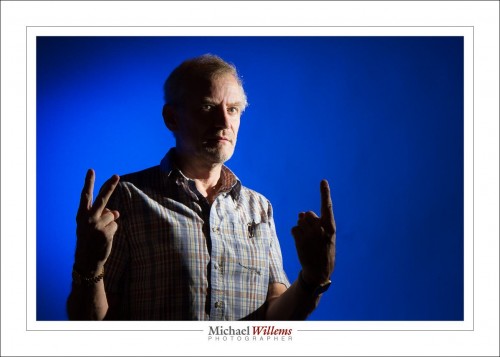

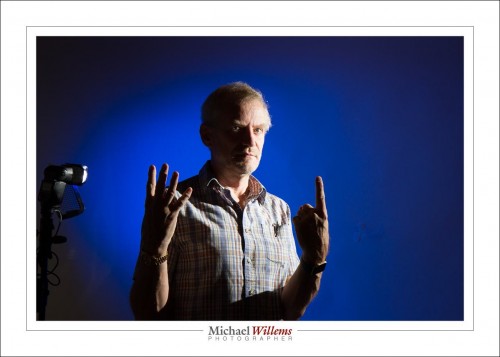

Now let’s move to manual flash. Manual is the opposite to TTL: it is utterly predictable and consistent but you need to do all the work, and it is totally useless when you and the subject move.

So I use manual when:

- I want consistency, and I can ensure that nothing moves (like in studio portraits).

- I have time to meter.

- The flash is just adding light, like an accent, or like fill on a sunny day, when the exact power level is not that important (if the flash were a bit under or over it would not make a material difference to the image)

- I am using Pocketwizards, e.g. for outdoors shots – which will therefore need to be predictable.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the predictability of manual flash firing, not to mention the predictability of the use of Pocketwizards.

So in fact I shoot manual flash if possible, and if not, then TTL.

Do I sound like I am contradicting myself? No. Because I shoot events. And events mean I need to be on my feet in a constantly changing environment. And that is when TTL shines (pun intended). Every shot I am in a different room, and I bounce off different surfaces. So that is why I usually use TTL.

And when using TTL, it is all about knowing how it is going to react, and being able to solve the problems. That is what I teach in my courses (e.g. at Henrys School of Imaging, and in the all-day course coming up on 30 May, and in Las Vegas on July 12+13, and many more times in between). There’s a lot of problem solving, involving tools like:

- Flash lock (FEL/FVL)

- Fast flash

- Flash compensation

- Knowing exactly what it will do

Remember, while a setup shot has to be right, in a fast-moving event, the objective is to get within half a stop to a stop, as long as you shoot RAW. And believe me, this is eminently doable.

Another sample from Wednesday, where bright ambient light necessitated 1/400th second, which meant using Fast Flash:

Oakville's mayor Rob Burton and family

Snacks, also from Wednesday:

Snacks at a high-end reception

Do try to bounce, and use you camera on manual settings (flash is still measured). The following may work, but only if you are lucky:

Photographer using popup flash

I would like to see her shots, but I know they would be better if she used an external flash and bounced it off the ceiling behind her!