In the continuing series on flash and its complexities that I started yesterday, time for the next basic subject. And that is “metering” and “exposure compensation” while not using a flash. (Yes, to understand flash you need to first understand non-flash exposure basics. So bear with me in this series.)

What does your light meter do?

When you press down the button half way while pointing at your subject, you activate the light meter – and the camera now does one of two things:

- If in manual exposure mode (M), it merely shows you a light meter in the viewfinder. You can now adjust aperture, ISO and/or shutter speed, and when you achieve “meter in the middle” this means “well exposed (if the subject is mid-grey)”.

- Or when you are in an automatic mode (P, A/Av or S/Tv), the camera itself sets aperture and/or shutter to make the meter go to the middle. The picture will therefore be well exposed (if the subject is mid-grey).

Let’s look at that qualification: “well exposed (if the subject is mid-grey)”.

- Your light meter – a reflective light meter – is calibrated to give you the “zero” reading when your subject is exposed to look mid-grey, i.e. neither very dark nor very bright. That’s just how it was decided it should work. Because most of the world is like that.

- So as long as what you are shooting is neither dark nor bright, all is well. Aim at zero and shoot, and all well.

So what if you are shooting dark or light subjects?

Let’s start with what happens if you are aimed at a dark subject:

- Setting the meter to zero gives you a light grey subject – not a black subject!

- So you need to somehow make the meter point at minus – say, minus two for a black subject.

- That way the subject will not look grey, but darker.

- Which is good – because since it is darker, it needs to look darker!

And what if you are aimed at a bright subject?

- Setting the meter to zero gives you a light grey subject – not a white subject!

- So you need to somehow make the meter point at plus – say, plus two for a totally white subject.

- That way the subject will not look grey, but lighter.

- Which is good – because since it is lighter, it needs to look lighter!

Your light meter does not know whether you are shooting a coalmine in the dark (total black) or a snow-hill on a bright day (total white). It cannot know. So you will always need to compensate for this.

How do you adjust?

If you are using manual, you adjust aperture or shutter or ISO until the mater moves to the desired setting. If in an automatic mode like P, Tv/S, or Av/A, you use exposure compensation (“the plus-minus button”) and set that to minus or plus – the camera now adjusts aperture, shutter or ISO. So the adjustment

Real-life example 1:

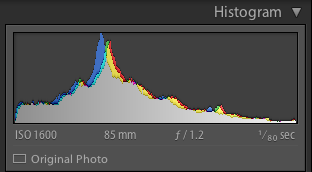

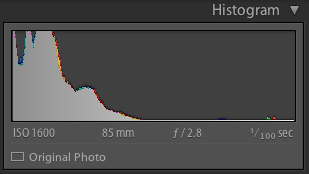

Here, a viewfinder-filling black bag with the camera on “P” (or on “M” where we make the meter go to “zero”):

And here, the same viewfinder-filling black bag with the camera on “P” with exposure compensation (the +/- button) set to minus two (or on “M” where we make the meter point at -2):

“But making the exposure go to minus two will make the subject all black, Michael”.

Yeah. And that is what we want, since it is black!

Real-life example 2:

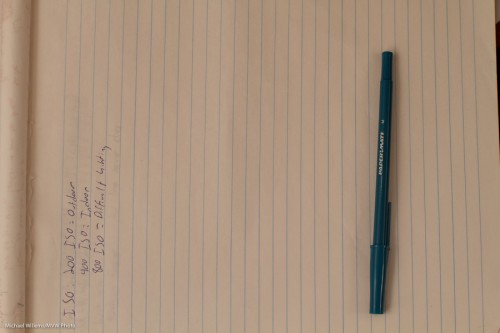

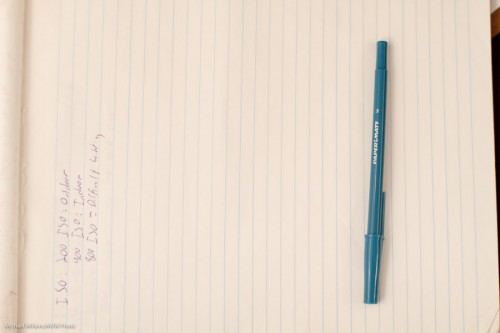

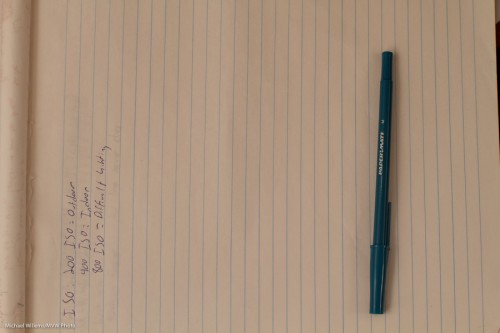

Here, a viewfinder-filling white sheet of paper with the camera on “P” (or on “M” where we make the meter go to “zero”):

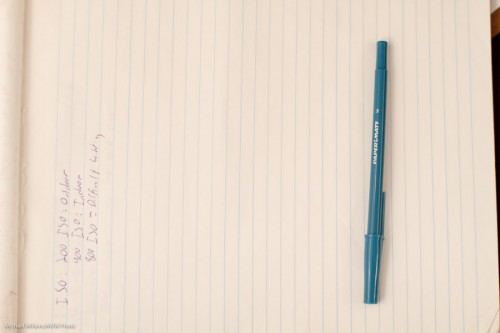

And here, the same viewfinder-filling white sheet of paper with the camera on “P” with exposure compensation (the +/- button) set to plus one (or on “M” where we make the meter point at +1):

“But making the exposure go to plus one will make the subject all bright, Michael”.

Yeah. And that is what we want, since it is bright!

Conclusions:

So, no magic. Just logic. Simple:

- If a subject is lighter than average I need to make sure it shows as lighter than average, and if a subject is darker than average I need to make sure it shows as darker than average.

- I can make these adjustments in manual mode by changing aperture/shutter so that the meter does not point at zero.

- Or I can make these adjustments in automatic modes by using exposure compensation (and now the camera does exactly the same: it adjusts aperture and/or shutter).

In the next while, more – but first, start by understanding this. A good way is to use manual mode for the entire day tomorrow, and only available light.

Have fun!