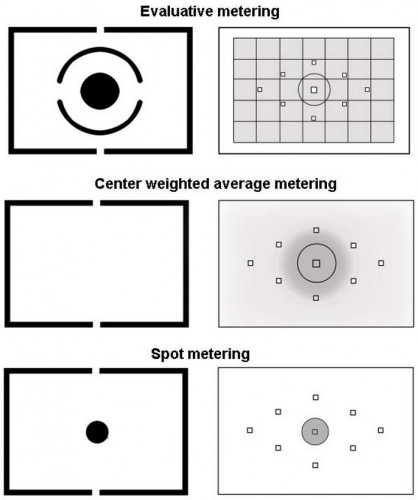

Your camera behaves in one of several possible ways when spot metering; and it behaves in one of several ways when using evaluative metering.

When spot metering (at the bottom in the graphic):

- The camera only meters what is happening at the centre spot

- OR the camera only meters what is happening at the focus spot you have selected.

It is easy to determine what it is on your camera. Shoot a scene with dark and light areas. Taking care not to move the camera at all between shots, shoot with the spot aimed at a light part of the shot; then shoot with the spot aimed at a dark part of the shot. If the exposure varies, your camera meters at the focus spot; if not, it meters at the centre spot.

When doing evaluative/matrix metering (a the top):

- The camera evaluates the entire picture, and chooses the best exposure to suit the entire photo.

- OR the camera evaluates the entire picture, and chooses the best exposure to suit the entire photo, biased to the selected focus point.

Again, it is easy enough to determine which one it is, using the same test.

My Canon 7D, for example, does the first option (centre point only) when spot metering, and the second option (bias to chosen AF point) when set to evaluative metering; while my 1Dx can be set to do either (using a custom function named “Spot meter. linked to AF pt”). The 7D, therefore, might seem to only do spot metering when it is not set to spot metering. Can you see how this can be confusing?

Did you know which it is, on your camera, before testing? If not, this will explain a lot of the “incorrect exposures” you have been seeing over the years. Yes, you need to know this stuff!

I remember a hardcover book. Pastel coloured pictures. “See Dick. See Jane. See Spot Run. Run Spot Run”. My memory is visual.