I regularly mention that the lens is the most important part of your equipment. Great lenses especially add to your photo-taking capabilities. Now let’s look at one aspect of that greatness again: the “speed” of a lens.

Speed is of course a misnomer. When we say “a fast lens” we simply mean “a lens with a large aperture (low “f-number”). This large aperture lets in a lot of light, which makes it possible to shoot at faster shutter speeds at the same ISO, hence the word “fast”. So a low f-number means you can obtain faster shutter speeds under the same conditions.

Like the 50mm f/1.2 lens I am selling (sadly; but I bought the 85 f/1.2 and I cannot financially justify keeping both these lenses; and for wedding portraits, the 85 will be more useful).

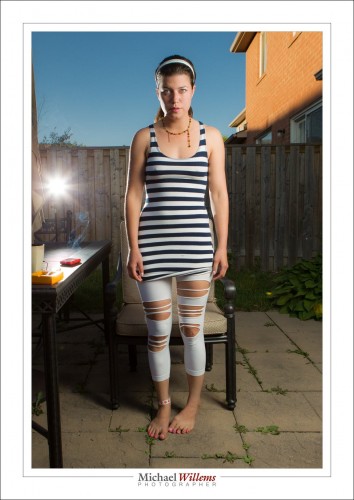

Here’s student Becky with the 50 f/1.2L mounted on her Canon 6D last night:

I was able, by using the large aperture of my own f/1.2 lens, to take that picture at a fast shutter speed, handheld. And I get a blurry foreground and background at the same time, which helps me to emphasize the subject.

How fast? Let’s look at a real example from last night.

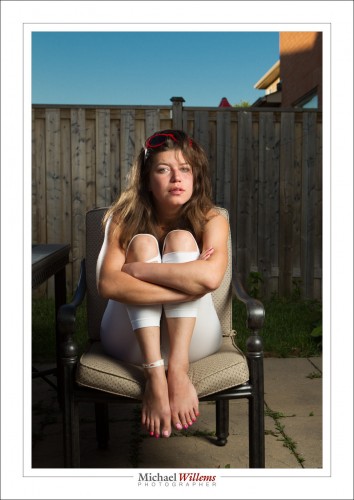

A shot of a glass of wine. That is what I focused on, so that is, of course, sharp:

I shot that at f/4.5, which is typical of the kind of lowest “f-number” that a kit lens would allow you to use. At 1600 ISO, that necessitated a shutter speed of 1/30th second. That is at the limit of what I can hope to do handheld; in fact it is beyond that “rule of thumb” limit, with an 85mm lens. So I am lucky that the shot is sharp. Also, I am lucky that nothing in the photo moved, because pretty much any motion would show, at that slow a shutter speed. And yes, the background and foreground are blurry – but they could be blurrier.

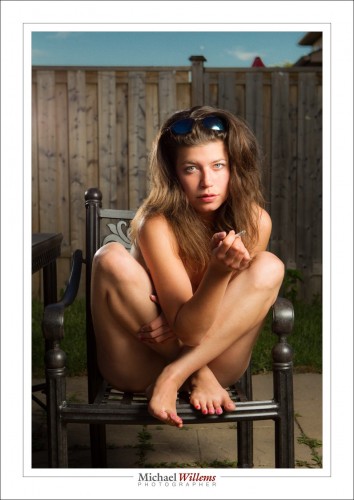

Now the f/1.2 lens, this time wide open at f/1.2:

The “f/1.2” means that:

- At the same ISO value, I now needed only 1/320th second shutter speed. I.e. a much faster shutter speed (i.e. less time; shorter time period; all these mean the same thing). That means I can easily hand-hold, and also I need not be afraid of motion.

- The lower f-number also allows me to through both Becky and the chips in the foreground way out of focus. The glass is still sharp (I am, after all, focusing on it!), but the depth of field at this low f-number is extremely shallow; meaning that foreground and background are very blurry indeed.

Now, I do not of course always want shallow depth of field; but the point is, that with a fast lens, I can. And that expands my picture abilities; in a dark evening setting I can shoot handheld without flash, and if I want, I can get extremely blurry backgrounds. And that is one of the reasons that I use an SLR in the first place. And any SLR would do this – it’s the lens, not the camera, that determines these things.

Which is why I am happy to spend on lenses. What’s not to love?

And a good lens lasts decades, both in technical terms and in value. So if you are going to spend, and why not; then spend mainly on lenses.