A student told me today that she had issues with shooting in manual mode. Especially, she says, in difficult circumstances.

Well, here is my answer. Yes, it is tough. “Less than ideal circumstances” is as much of a problem for me and everyone else as it is for my student. That is why we buy expensive lenses (low F-numbers let in more light; expensive cameras allow very high ISO values, and so on). Perhaps my student found it tough because it is impossible with her equipment.

But the principle of exposing right in manual mode is still simple. If it is too dark in your photo, you can do exactly three things (apart, of course, from turning on more lights). Same for my student as it is for you and for me.

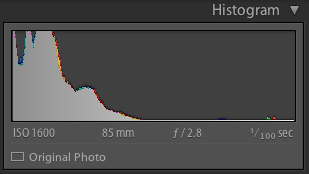

1. Increase the ISO

Drawback: more grainy pictures

Limit: your camera only goes so high

What the pros do: buy an expensive camera that works well at high values

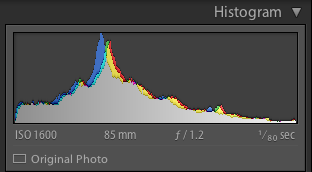

2. Lower the F-number

Drawback: you get less depth of field, which sometimes you want.

Limit: your lens only goes so low.

What the pros do: spend lots of lenses with low f-numbers

3. Slow down the shutter

Drawback: you get motion blur in your photos.

Limit: anything slower than, say, 1/60 sec will give you motion blur.

What the pros do: not go too slow. Or use a tripod..

So if your picture is too dark, you just have not gone high enough (iso) or you just have not gone low enough (f-number) or you just have not gone slow enough (shutter). Not difficult.

And you can use a trick! Let’s start with that trick.

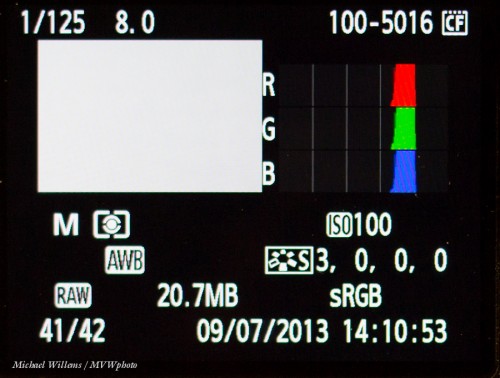

- Go to PROGRAM Mode (P)

- Press the shutter slightly so you see the chosen aperture, shutter speed, and ISO

- Write those down.

- Go to MANUAL mode (M)

- Enter those values for ISO, aperture, and shutter.

- Now start varying from there. See what happens when you vary each of the parameters.

It really is as simple as that to get a good starting point. And you can also get good starting points for the variables. Like ISO: 200 outdoors, 400 indoors, 800 in tough light. Or shutter: keep above 1/60. Or aperture: open up indoors (low “F”), and stop down outdoors (high “F”).