One reason we bounce our flash off the ceiling (behind us) is to avoid those nasty drop shadows, especially the side shadows.

But what if we can’t? If there is no ceiling, perhaps. Or that ceiling is bright red. Or it does not reflect enough light, because it is pitch black. or it is a very high ceiling. What then?

Then we can use many other means, like reflectors. Or off camera flash, with modifiers. Or a ring flash. Or we simply ask the subject to move to where it is possible (d’oh!).

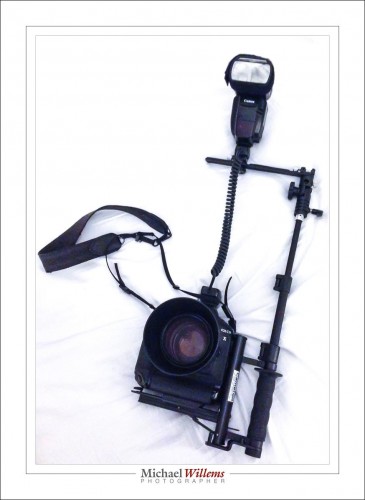

There is one more option, one I have not discussed before: we use a bracket to move the flash away from the camera and keep it above. Like this Cameron V-H Flip bracket (marketed under various names):

It has some pretty good features:

- It moves the flashes away from the camera, see the extending pole. Up to 28″ above, and this means that there will be less shadow and no red-eye.

- It keeps the flash(es) directly above the lens, so any remaining shadows will not be side shadows.

- It can fit two or even three flashes.

- It swivels, to keep the flash where it is while the camera turns 90 degrees (but note, it turns the wrong way, which is awkward. I would not want to use this bracket for a lot of vertical shots).

- And unexpectedly, this bracket can use a small umbrella. You’ll look funny, but oh boy, the light you will get!

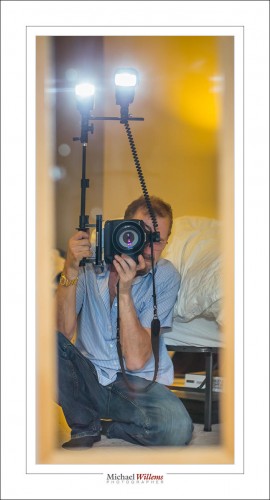

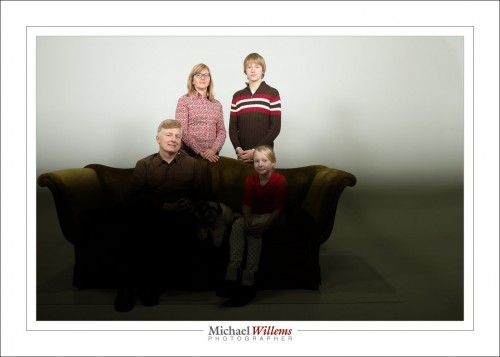

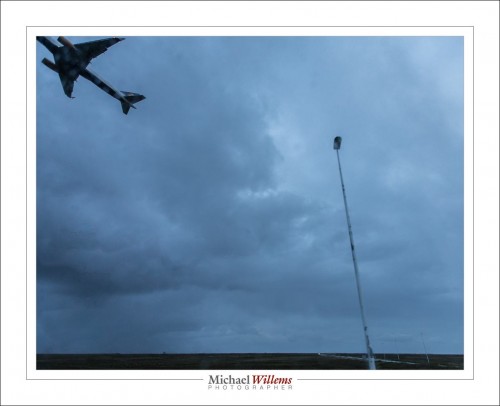

While bouncing, or off-camera flash with modifiers, is generally still better, this solution can work well:

Best of all, it can hold two (or even three) flashes:

Now we get extra light, plus the light from one flash can almost eliminate the shadow from the other.

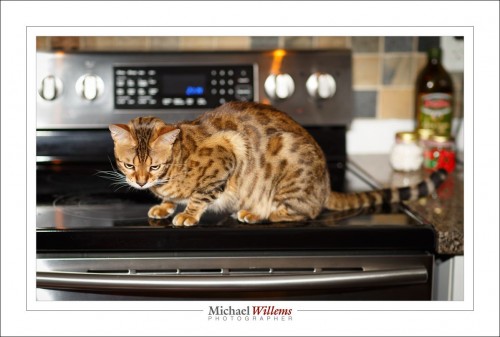

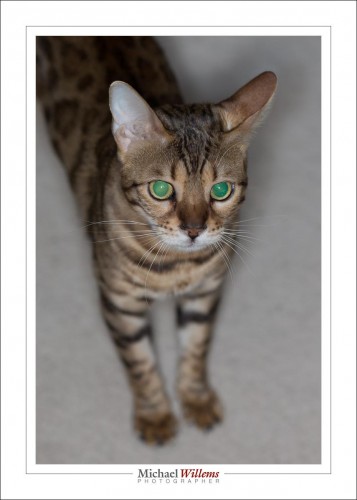

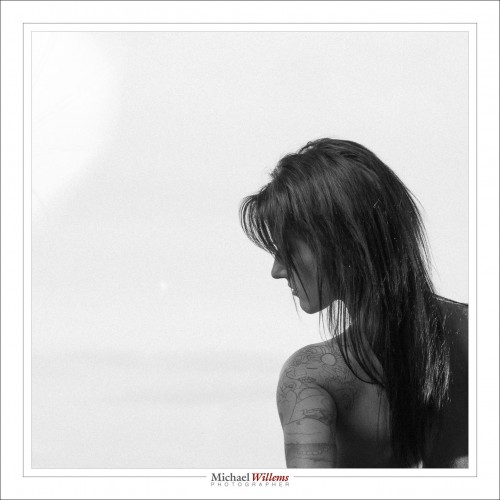

That doesn’t look like a “direct flash:” photo, does it? And beauty pictures, with a small modifier, seem another obvious candidate (“butterfly lighting”).

The moral of today’s post: There are many ways to use flash, and there are many ways to use it well. A bracket is one of those ways. Not the be-all and end-all of flash; just one more cool tool that can sometimes lead to fabulous pictures.

___

Footnote: Have you considered really learning flash? Worth every hour—and dollar—that you invest in it. See learning.photography for a good option. And don’t forget to order the flash manual now. You’ll know the secrets the great pros know; and more importantly, you’ll be able to use them.