A friend pointed out something that you should know, and that I did not point out again in my recent point about ND filters. Namely this: OK, so you need them for waterfalls. What else do you need them for?

The other reason you need them is to get blurry backgrounds outdoors, particularly if you are using flash.

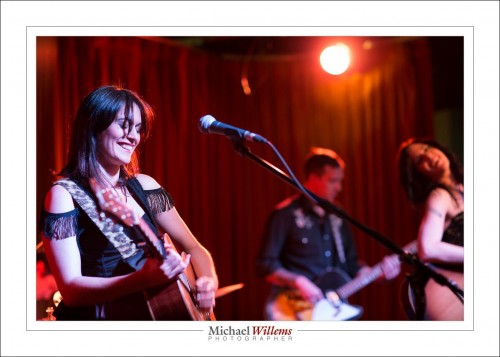

Let me explain. Take a shot like this:

That was 1/4000 sec at 400 ISO at f/2.8.

- It has the blurry background I wanted.

- Which I achieved with the large aperture (low f-number).

- That large aperture necessitates a fast shutter speed.

But – uh oh. When I use a flash (which I might well want, in a picture like this), I cannot go faster than my flash sync speed, namely 1/250 second (if you want to know why, buy the Mastering Flash e-book). So then I’d have to slow the shutter to 1/250th, and the picture would be overexposed.

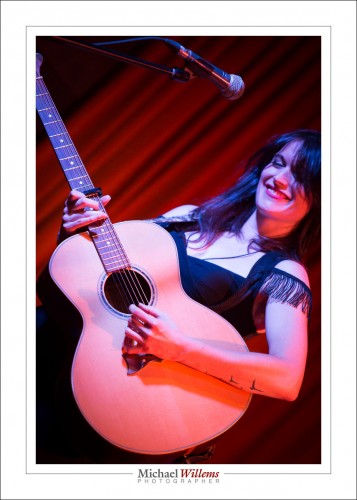

To prevent that, we can use not f/2.8 but f/11:

(400 ISIO, 1/250 sec, f/11).

Fine. But—uh oh—now the background is not blurry enough. See:

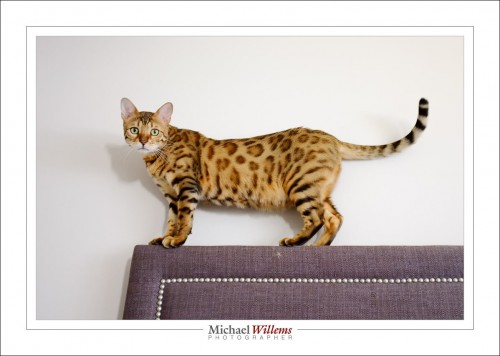

So here comes the ND filter to the rescue:

- If the ND filter cuts one stop of light, you need f/8 instead fo 11.

- If it cuts two stops, you need f/5.6.

- Three stops, f/4.

- And finally, if it cuts four stops, you need f/2.8. And my filter cuts four stops of light.

So that gives us:

(400 ISO, 1/250th sec, f/2.8)

And that is exactly what we want. Identical picture to the first one, but with a slower shutter speed, 1/250 sec instead of 1/4000 sec.

In simple words: an ND filter allows you to use a lower f-number without having to increase the shutter speed to a faster value (which you do not want to do because of flash).

(Do note this, however: the flash now also has to punch through that ND filter’s darkness. I.e. my aperture may be f/2.8, but as far as my flash’s amount of light is concerned, it looks like f/11. Meaning I may not have enough power to bounce, etc.)

___

Go get all five of my e-books now: Special deal. Go to http://learning.photography and before the last click, enter discount code “Speedlighter” for another 10% discount on top.