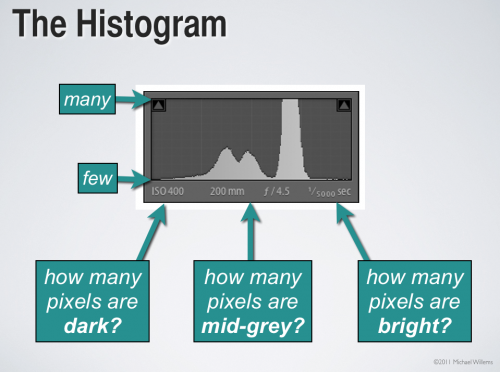

What is the graph you see on the back of your camera when you press the “DISP”, “INFO”, or “up” or “down” buttons on the back of your camera?

It is called the Histogram. It should really be called the “Exposure Histogram”.

It tells you about your exposure in much more detail than a light meter does. In a way, it is like 256 little light meters in one.

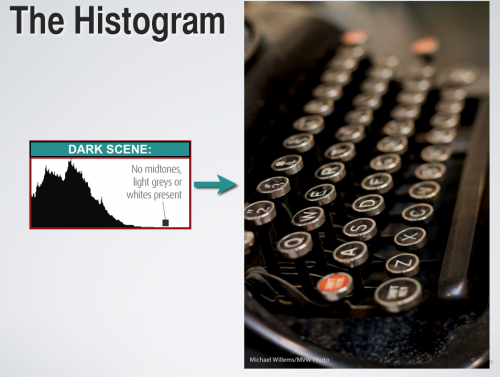

A histogram of a correctly exposed dark image would look like this (unless you are shooting RAW and “exposing to the right”, which is a good technique – but more about that again some other day):

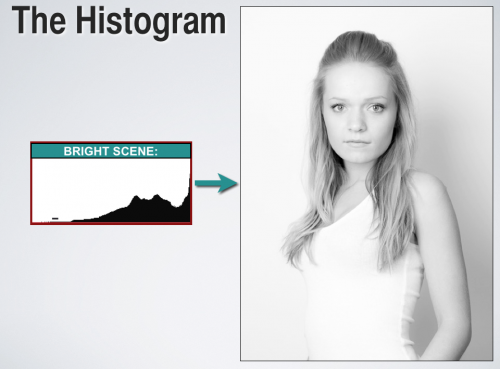

And a histogram of a correctly exposed overwhelmingly bright image might look like this instead:

The words “correctly exposed” are key. If you expose either of the images above incorrectly, you would see a different histogram than the ones above. And that is the power of the histogram: it helps you expose correctly.

Try it now: go shoot a black bag or coat or wall. Fill the entire viewfinder with that bag or coat. Now check the image – and the histogram. Then do it again, using exposure compensation to get a correct histogram.