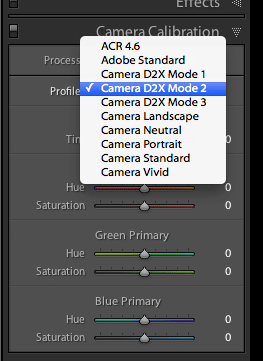

Lightroom 6 is the latest and greatest in the version history of Lightroom, the best thing since sliced bread. Asset management, editing, and production all rolled into one.

LR 6 is a worthwhile upgrade; as I mentioned in an earlier post, it has lots of new stuff. For me, the main features for me are:

- Face recognition. You can now recognize faces, so that all photos that feature uncle Bob can be quickly found. Remarkably accurate

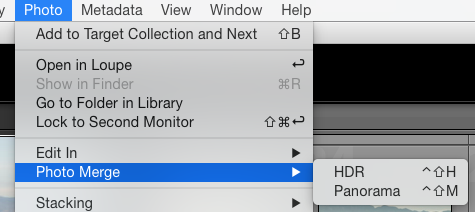

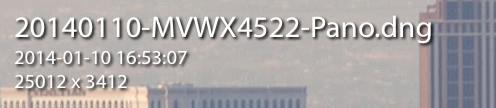

- Panoramas. Stick together 2, 3, 4, or more overlapping photos that you have shot.

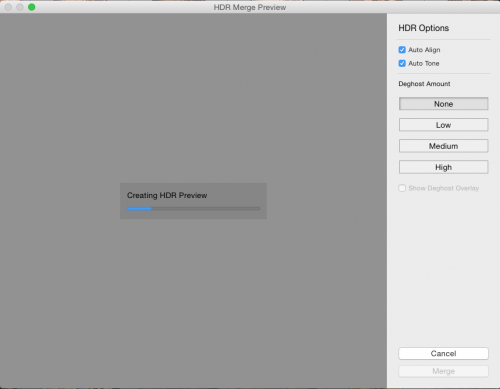

- HDR. Stake one normal shot, and one more more darker and one or more lighter, and pull them together to get either artistic “paint” effects, or just more dynamic range (i..e. the detail in the dark areas will be visible, as well as detail in the light areas).

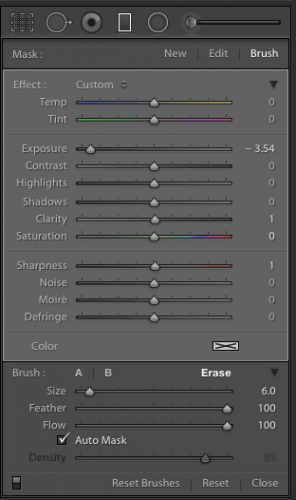

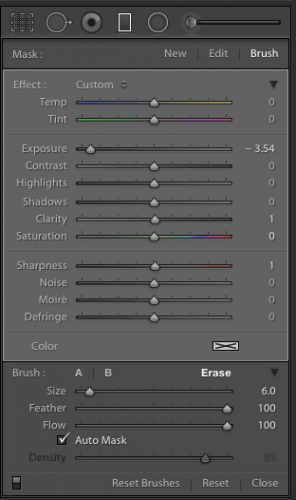

- Brush in filters: you can now use a graduated filter and remove it (or add it) in specific, brushed areas:

(The graduated filter here has the new BRUSH activated in ERASE mode, so I can delete part of the filter)

There’s more, especially the Mobile functions and the reputed speed increase, but I cannot comment on that since I have not observed or used them.

So, how to go about upgrading?

First, make sure that you have backups. And I mean good, verified backups. You never know. Don’t ever lose all your work… make backups and store them off site. Backups of both the photo originals and the work you have done on the (the catalog file, named <something>.LRCAT).

Then, the upgrade. Under “Help” select “check for upgrades”. Make sure that if you have the app, you keep getting the app, and not the “creative cloud”. Adobe really, really wants you to get the Cloud version, which works out much more expensive even in year one if all you use is Lightroom; and after year one the price will go up. You will have to search the Adobe site; look for “All products”, and look for the price of around $80 for the upgrade. Not the $3-10 per month Cloud price. (Think about it: if the next upgrade is two years away, and I only use Lightroom, I pay $80 for those two years. Cloud users would pay significantly more: 24 times something is something big.)

Before you start, you will need to log in to Adobe, and under “My products”, find the serial numbers for previous versions. You will need the previous version’s serial number to qualify for the upgrade.

When, armed with the login and the serial number, you perform the upgrade, your catalog file will be converted. This takes time. On my catalog, with around 200,000 photos it took most of the overnight that I let it run.

At the end, when you can use Lightroom, you will have a new catalog. But your old catalog will also still exist. Just in case. I advise you keep that around for a little while. Just in case. You never know.

Also, make sure that when you want to use Lightroom you start the new app, not the old one. The new one is called “Adobe Lightroom” and lives in your app folder, inside a folder called Adobe Lightroom.

After the upgrade you will see that Lightroom works as it did before. But new functions have been added. Under “Photo” you can now, after selecting two or more photos, select Panorama or HDR (high dynamic range). Try!

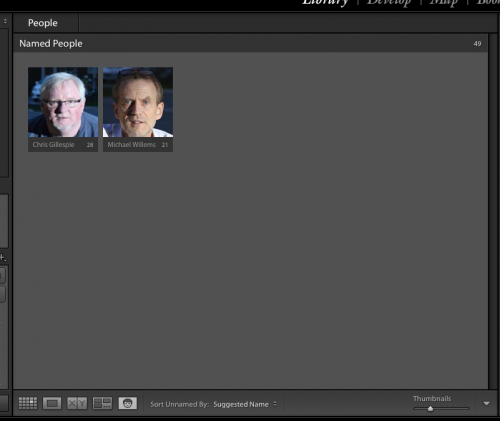

And more importantly, in the grid view you see a new face symbol as one of the following views. Bottom right:

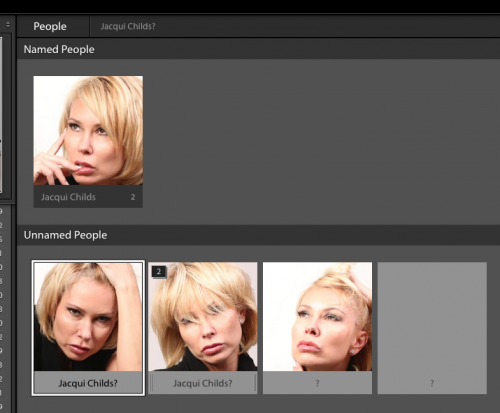

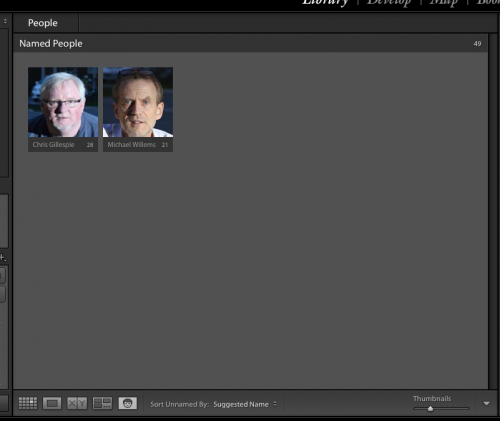

When you click that, you will see the faces Lightroom recognizes. Give them names. Over time, Lightroom gets better and better at naming faces. After you name them, you see:

Initially, of course, all faces are unnamed.

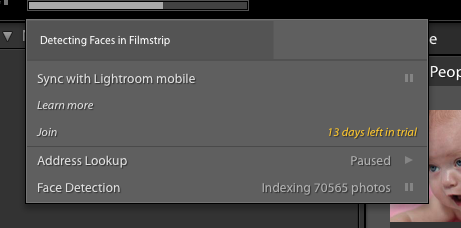

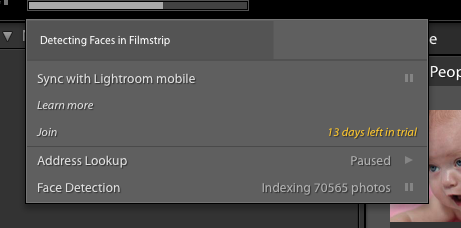

You can turn face recognition indexing off (paused) or on by clicking on the Lightroom Logo on the very top left of your screen. You see:

During this time, the application may be slow, not just when you are looking at the grid view, but also when exporting a picture, printing one, and so on. Allow plenty of time for the indexing to finish, and you can pause the indexing when you need speed. You can index per shoot, or per year, or all at once (though I would not recommend that when you have a large catalog, like mine).

I am still discovering new things, so there will be more blog posts about Lightroom 6. For now, though: recommended!

___

I also coach privately: bring me your laptop and I will not just teach you, but we will set up your own Lightroom installation in the optimal way. See http://learning.photography.