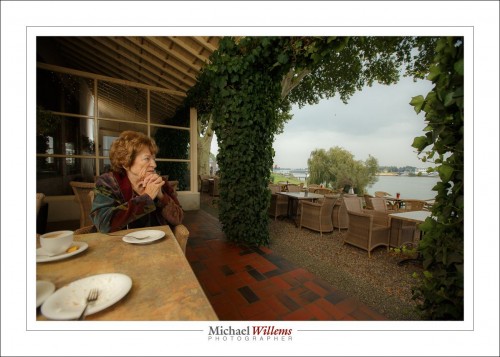

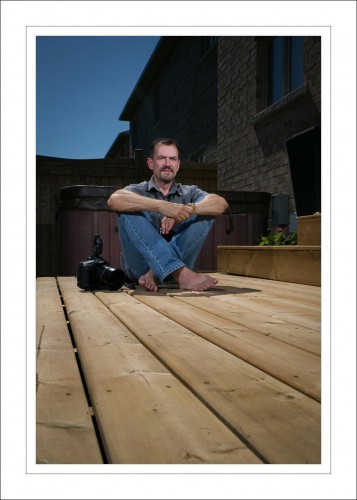

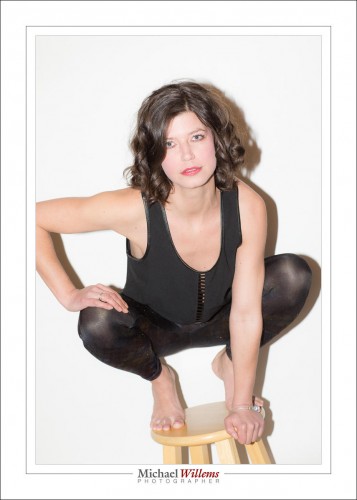

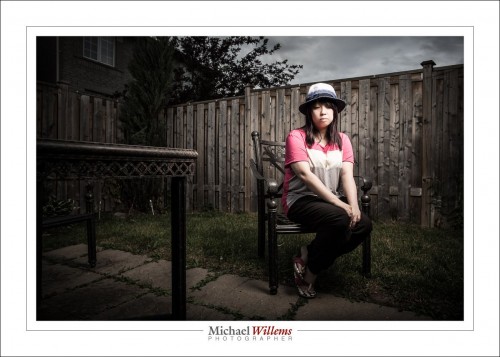

More and more, I think of how to best convey my knowledge. Everyone can learn photography, and preserving moments in one’s life is so important that everyone should. My mission is to help you learn. And if you are a working pro, my mission is to fill gaps and to teach you modern techniques like flash, video on your DSLR, studio lighting, and so on.

I do this blog, and its daily posts, for you for free, so perhaps you will forgive me for once for going all commercial on you. After all, it is to help you by facilitating learning.

So—how?

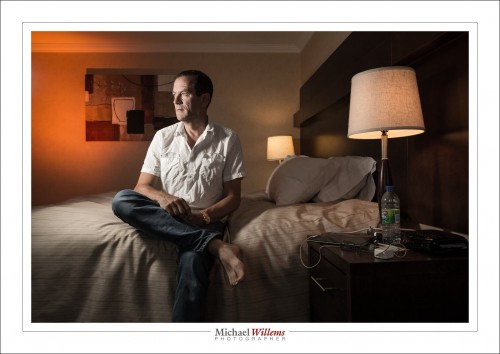

First, there are the e-books, of course (http://learning.photography/collections/books). I am proud of them: they condense 10 years of teaching into five books (book 6 is on its way, and it is the largest one yet).

These are, if I say so, very well thought out, well written and well illustrated, long (all over 100 pages, some much more), and easy to use (simple PDFs which you can put on all your devices without hindrance, or even print: a license for that is included).

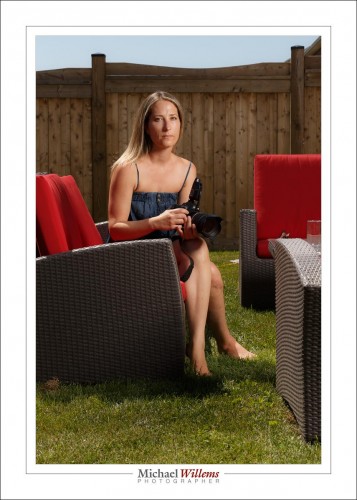

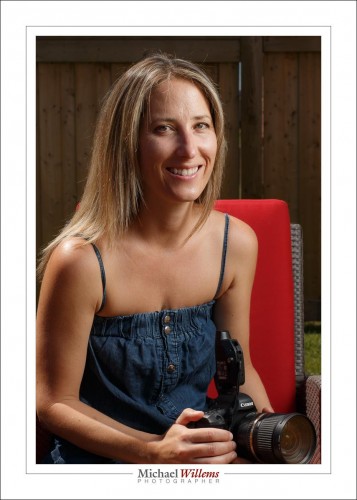

But learning is best done by adding personal training. You can do that at Vistek, where I am due to teach some more courses next month, and at Sheridan College, where I teach regular evening courses. But best of all, you can do it as private or semi-private courses. See http://learning.photography/collections/training — and those are starting points; in fact if you come to me we will fine-tune the course to your exact needs. From one two-hour session to a full multi-0week course with assignments and review.

So here’s a few suggestions:

- Before the festive season, learn to do it properly. Reserve your photography courses now: there is limited space and prices will increase before November. If you book now, you will get the old price, regardless of when you take the course.

- Better still: reserve your course before November, and receive an e-book of your choice free of charge.

Also, think of others around you who want to learn photography:

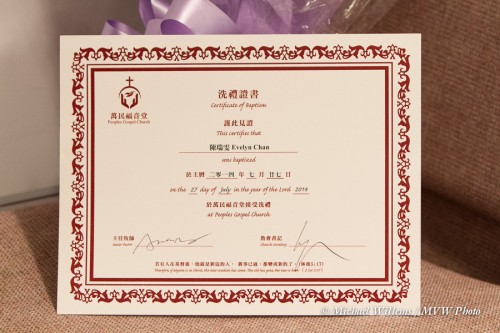

- Buy a Gift Certificate for one or more courses. These are NOW available! They look good, and again, if you buy the certificate now you can take the course any time in the future. Click here to see/order your certificate.

- Gift the e-books. Nothing better to go with camera gifts than e-books that explain how they work and how best to use them. Books are available as a download link on a certificate, or on a DVD for immediate reading.

So as you see, there’s plenty of options for you and your loves ones to learn.

Have needs that are not met by the above? Then call me (+1 416-875-8770), email me (michael@michaelwillems.ca) or contact me any other way you like, and let’s discuss.