…or “to the light”.

But contrary to that Latin phrase, a little tip today for when you don’t want light. Like when you want to hide something.

Hide something? Example, please?

OK. Say you have a roll of paper in your studio. and you want to shoot a full length portrait. Normally you would pull the roll all the way forward so the subject stands on it. No transition can be seen at their feet because there is no transition.

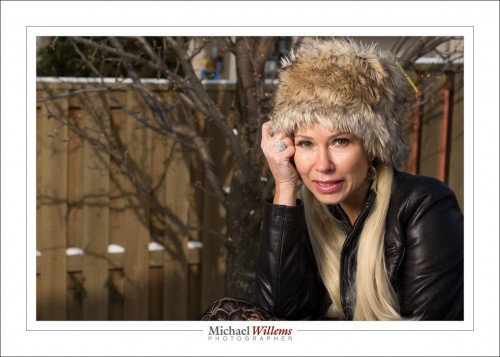

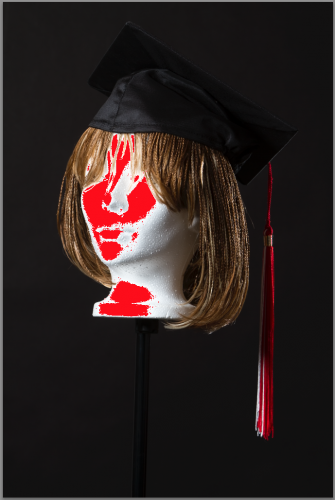

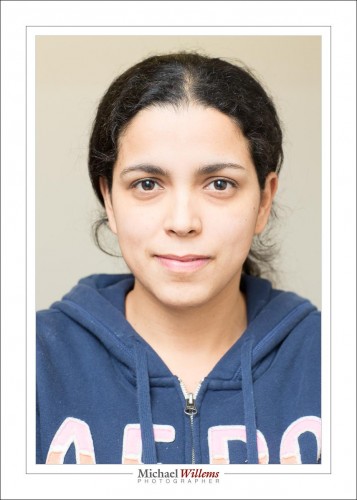

But if the roll is too short? Then you will see a clear (and ugly) transition from “floor” to “roll”:

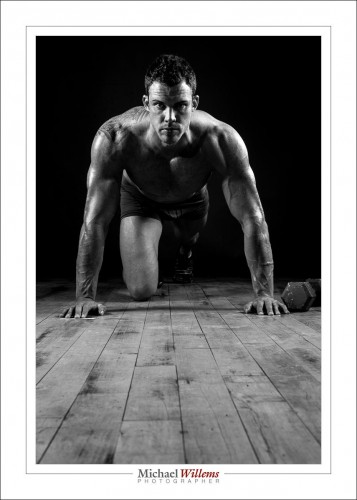

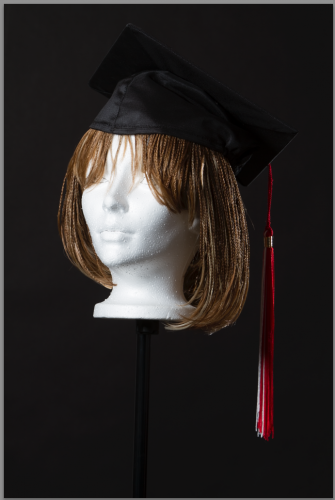

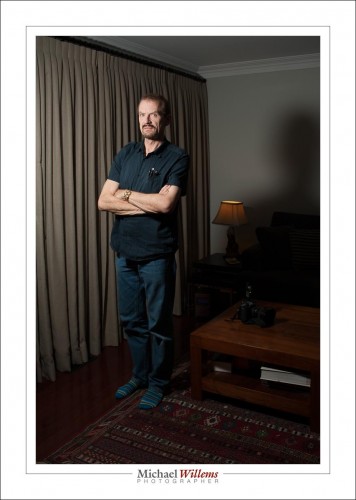

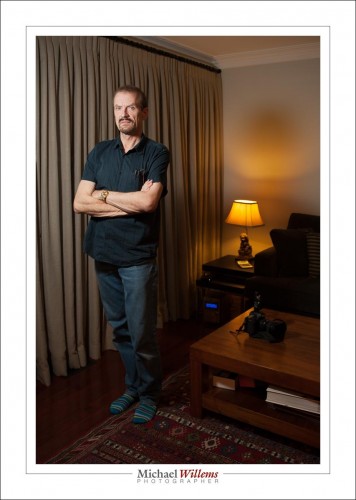

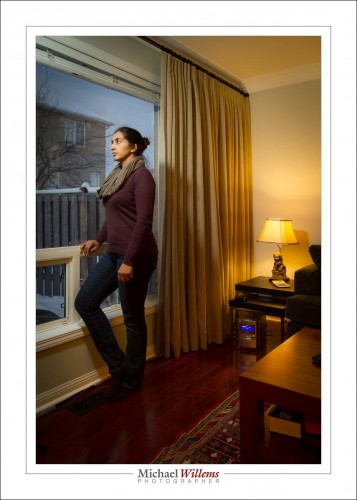

But this is solvable. It is in fact simple: keep the transition in the dark. Then you will not see it. Like this:

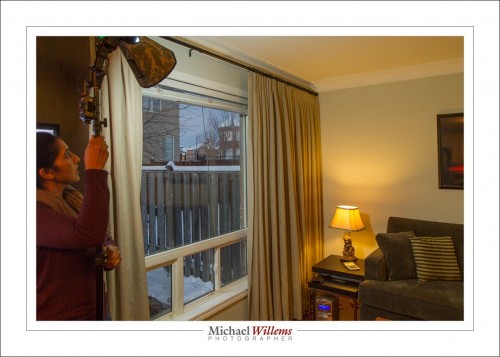

To keep it in the dark, you must do two things:

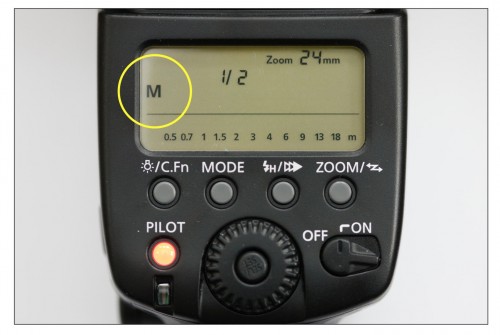

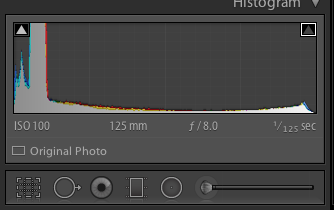

- Set the camera so that ambient light plays no role (i.e. without flash, the picture is all dark), Standard settings like 1/125 sec, 100 ISO, f/8 will take care of that. This means all light in the photo will be from your flashes.

- Ensure your flash light does not reach the transition. By definition, that will result in the area being dark. So you need to point away from the area and have enoughdistance from the background.

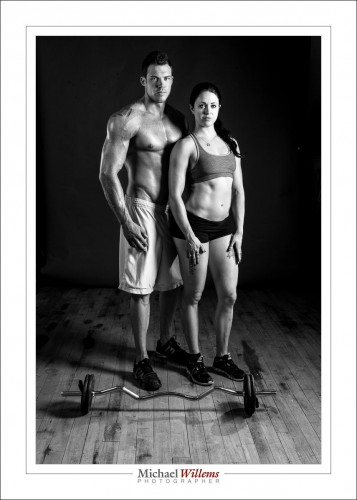

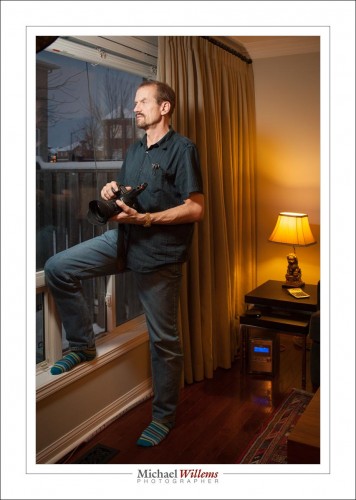

That is it. So if I use two softboxes as above, and feather them away from the background, I will not throw any light on the background. That means it will be dark. And since the floor is light when you are, it will be a gradual darkening.

Simple. Two softboxes and a too-short-really paper roll, and that’s the result. Things do not always need to be complicated.