In 2010, I wrote this:

I shot an event yesterday that prompts me to give you some TTL management strategies. This is a long post – one that you may want to bookmark or even print and carry in your bag.

TTL Management Strategies? Huh?

Yup. TTL (Through The Lens) flash metering is great, but it can have its challenges. Unpredictability, or perhaps better variability, being the main one.

So why use TTL at all? Well, for all its issues, it is the way to do it since you are shooting in different light for every shot, and you have no time for metering. Metering and setting things manually (or keeping distances identical) in an “event”-environment, especially when bouncing flash, is usually impossible. So TTL (automatic flash metering by the camera and flash, using a quick pre-flash) it is.

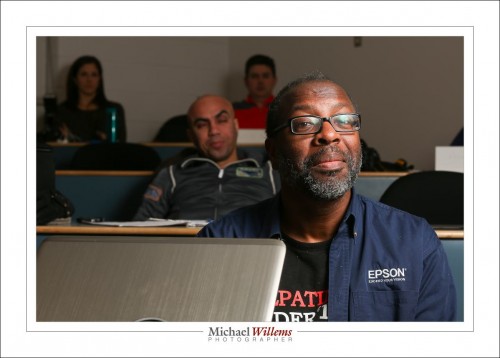

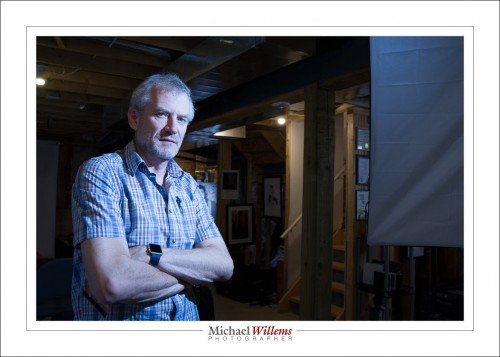

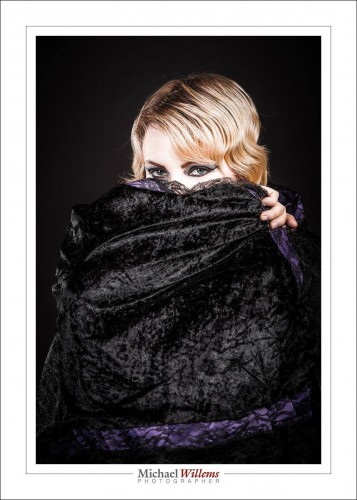

- Cheers! (a Michael Willems signature shot)

Yesterday’s event was in a restaurant that had been closed to the public for the night. Challenges for me were:

- Light. It was dark. Very dark, meaning achieving focus was tough and settings needed to be wide open and slow.

- Consistency. The venue was unevenly lit: parts were light, parts even more dark. Meaning that achieving “one setting” is difficult.

- Space. Space was limited: hardly enough space in a small venue to walk around, let alone to compose shots.

- Bounceability. Walls were all sorts of colour, mainly dark brown, making bouncing a challenge.

- Colour. This also created coloured shots. Orange wall = orange shot.

- Predictability. Long lens? Very wide? Fast lens? Every shot seems to need another lens – which is impractical.

- Reflections. There is a good change reflections of glass or jewellery will upset your shots, causing them to become underexposed.

- Motion. People kept moving (uh yes, especially when the chair dances started).

- Technology. Batteries run out. Flashes stop working. Cards get corrupted. Nightmare scenarios we all know.

- Time. People were not there for me – it was of course the other way around. So my ability to ask people to pose and to move was limited. They are there for a party, not for the photographer.

So then you shoot and you notice that shots are too dark. or too bright. Or faces are too bright while backgrounds are too dark. But this is all in a day’s work for The Speedlighter… that is what I do for a living!

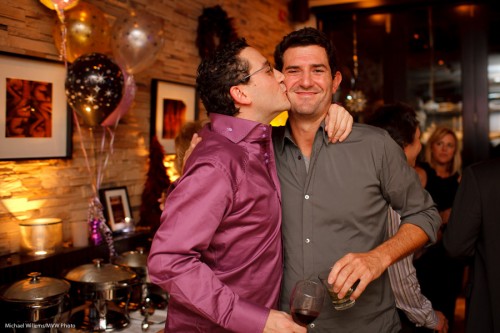

- Mazel Tov!

I am sure everyone who has ever shot events is familiar with these issues. To solve them and come up with solutions, I have developed a number of strategies. So let me share some of them with you here.

(Click to continue and read the solutions…)

First, and this is not what this post is about:

Know your camera intimately and use the standard settings. Like a safe start setting of:

- “Manual, 400 ISO, f/4.0 at 1/30th second”.

- Aim the flash 45 degree up behind you.

Your objective with this is to get soft flash light onto your subject and warm ambient light into the background. Try to get the meter to “minus two stops indicated” when you aim at an average part of the room.

To learn all about this, read this blog and take one of my courses, a one-on-one, or a Mono course, or do the Flash course with me at Henry’s School of Imaging.

This post, however, is about the next step, which I also teach in my upcoming “Event Photography” course, namely: how to reduce the variability and get consistently great results.

My strategies to achieve this include (and you’d better sit down for this one: there are 20):

- Choose lenses for success. A 35mm fast prime (or 24 on a crop camera) is a good start, and this is what I used most of last night, but wider (like a 16-35, or 10-20 on a crop camera) is sometimes easier in tough light and is often necessary when space is tight. Sometimes you’ll want a long lens. I carry two cameras an no more than three lenses at any events.

- Give yourself time. Do not allow yourself to panic: I see beginning photographers do this. Instead, take your time, and shoot many test shots; find your happy spot. For me last night it was 800 ISO, f/3.2, 1/30th second. It took me a good while to arrive at this! Shoot, regularly check the shot, and when you see a pattern emerge of good shots at a particular setting, use that setting.

- Focus carefully. This is crucial: it is very tough and can be slow in low light. The trick: aim your single focus spot at brighter, contrasty areas (like faces, contrasty clothing), then focus, then hold that and recompose. And watch your distance: focus on something the same distance as your subject. Otherwise you get blurry pictures – also, TTL is sensitive to distance!

- Meter off mid grey. When you do this focusing, you are also metering (unless you have separated focus and metering, which in an event shoot is not an obvious choice). So be careful. If you focus and meter on a dark area, the flash will overexpose. On a bright area? Then it will underexpose. Most cameras meter with considerable bias towards your chosen focus point. So try to focus on something that is neither very bright nor very dark.

- Avoid hot spot reflections. TTL metering (especially on Canon cameras) is sensitive to this. Result: your entire shot in underexposed. On some cameras you can set your TTL metering to “centre weighted average” instead of “Evaluative” or “3D Color Matrix” metering: some photographers choose to do this. In any case, be aware of windows, mirrors, anything that can cause this issue.

- Use Flash Exposure Compensation (FEC). If you know you are metering off a bright white area, turn the flash up a stop. Conversely, if your subject is small with a big background (a person against the room), that subject may be overexposed. In that case, turn FEC down a stop. You will be using FEC a lot in many shoots. During the evening, you will see where you need plus, and where you need minus.

- Use your histogram. Avoid judging your shots solely by the preview on the LCD. Use the histogram by checking every now and then. It is OK to “expose to the right” (search for that on this blog, if you do not know what it means).

- Do not obsess about previews. Take a look often, but do not obsess. Images will be better on your computer than on the LCD, in all likelihood. You are there to shoot, not to edit.

- Find good bounce areas. For every shot, try to find a bounce area behind and above that is bright-ish, and that when reflecting flash, throws light onto the front of your subject’s faces.

- Go to a higher ISO. In a dark environment, where you bounce off walls and ceilings that “eat”most of your light, you will want to use a high ISO, like 800. Sometimes even higher: I shoot in clubs at 1600 ISO quite often.

- Use rechargeable NiMH batteries in your flash. These charge your flash more quickly. Essential in a fast-moving event situation, so do not use ordinary alkalines.

- Change those batteries often. You will be shooting at high power, and soon your batteries will get hot and will stop working. Happened to me last night – so I changed batteries a few times. Do not worry about “but they are not done yet”. Change them while the going is good. Batteries never fail at a convenient time. Take charge!

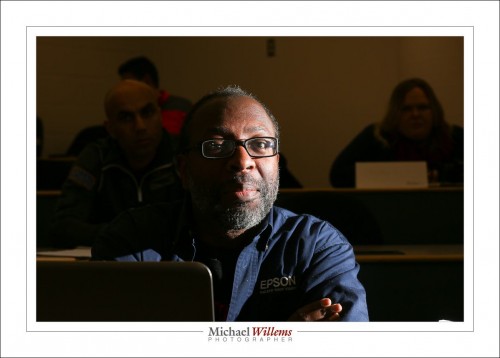

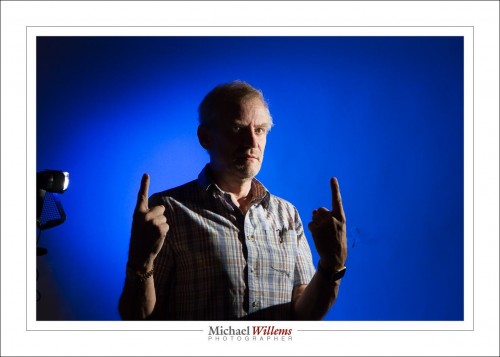

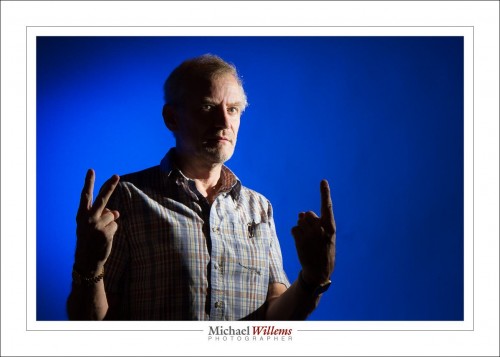

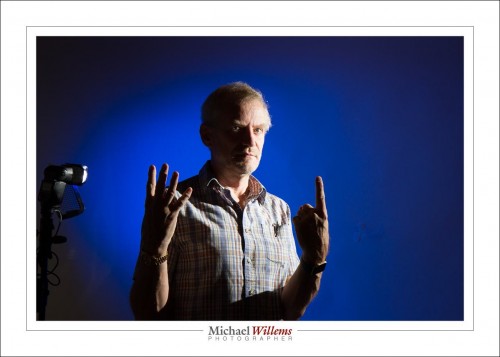

- Do safe shots. You will develop your style and this should include some safe shots. My signature safe shot is the “hold out your drink at arm’s length” shot I started this post with, above. Another safe shot is the food, shot at wide angle. Develop your own safe shots and always get some of those.

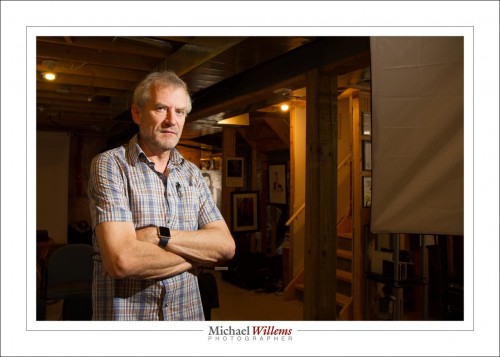

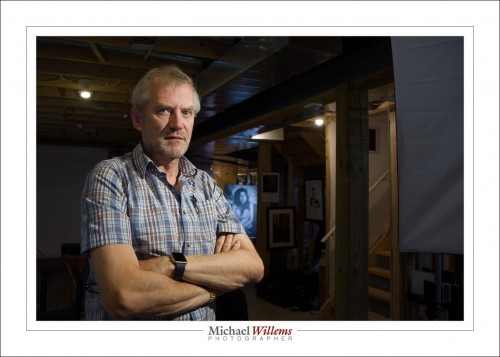

- Find good places. In an event location, there will be some shots (“in front of that great lit-up brick wall”) that work well for you. In that case, once you discover them, hang around those areas, even try to get people into those locations if you possibly can. The more of those you get, the more your ratio of great versus OK will go up.!

- Shoot ratios! This is a crucial point to understand. You are not in a studio environment. Not every shot will work. A failed shot or two is no issue. You are aiming for a good ratio between good and bad. I am delighted if 75% of my shots at an event are good enough to be shown. At a pinch, I will settle for half, if I must. This approach takes pressure off you. A bad shot does not mean you are a bad photographer.

- Shoot a lot. The ratio-approach I mention above means that event shooting is possible regardless of your expertise level: just shoot more. Tough light? Shoot even more. I do that too, and for for shots that I must get (mother with son, the happy couple, the main speech – that sort of thing), I always shoot two or three, even if I think the first one is good. So – shoot a lot.

- Do not delete bad shots in the camera. This takes time and wastes battery. You should be shooting, Also, you want to be able to tell your ratio of good vs bad – if you delete bad you will never know and you will never see the improvement.

- Shoot RAW- and try to get within a stop. Crucially, you do not need to get every shot right. If you are within about a stop either way of perfect you are just fine and the rest can be done in post. Events need much more post-production than studio work. Many shots will need adjustments: exposure, white balance, crop. Vignette, sharpening, skin adjustments.

- Do not worry about white balance. Set it to “Flash” and adjust later. That is why you shoot RAW.

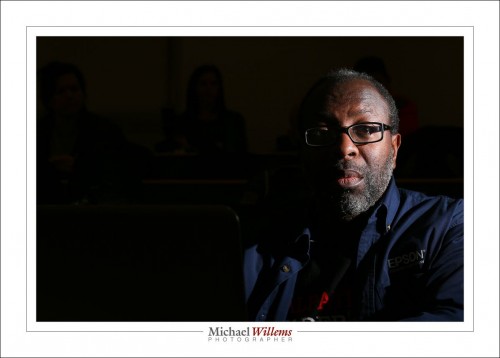

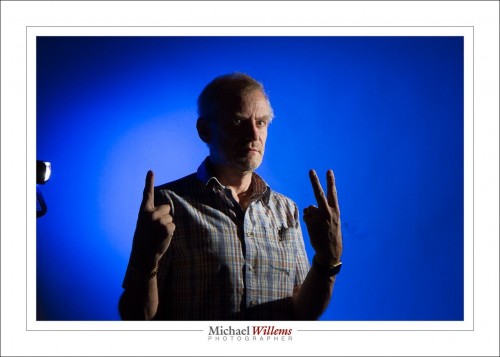

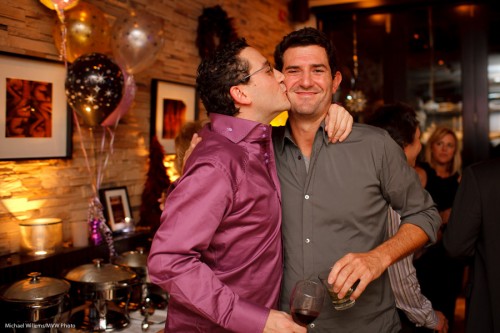

- Catch the moment. Often, this is more important than the quality! Choose the decisive moment. “If it smiles, shoot it”. Look for moments and “damn the torpedoes” – shoot! The chair dance shot above is a good example: yes, more light and no “exit” sign and a tighter crop would have been even better, but the moment beats all that.

Whew. A lot of strategies. Do not forget to have fun. Be a people person. Smile. Whatever you shoot, it will be OK, it will be better than if you do not shoot. get on with people, smile, laugh, eat and drink a bit if you are invited to. Enjoy!

- Kiss kiss! The decisive moment.

To learn the strategies, I recommend that you now read this post again, print it, and then start implementing the ideas one by one.

Practice makes perfect, you know what “they” say… and New Years’ Eve will be a great time for you all to practice.

And all that still holds today, of course!