High Speed Flash. Also known as High Speed Sync, or HSS, or “Auto FP” flash. Your camera/speedlight combination probably has it. Let me explain what it is, why it’s good, and why it’s nevertheless seldom useful.

First, the term “High Speed” is a misnomer, since it is actually slow speed flash. Let me explain.

Normally, a flash lasts 1/1000 sec or less. At 1/32 power, it’s only about 1/30,000 second. Very, very fast.

But there’s a problem: the shutter cannot keep up. You see, the shutter needs to be fully open for that quick flash to be able to illuminate the whole sensor, but at speeds above 1/250 second, the camera makers use a trick to get faster shutter speeds: instead of opening fully, an ever narrowing slit of light travels down the sensor, so the shutter is never actually fully open.If you try to use flash, only part of your picture will be illuminated.

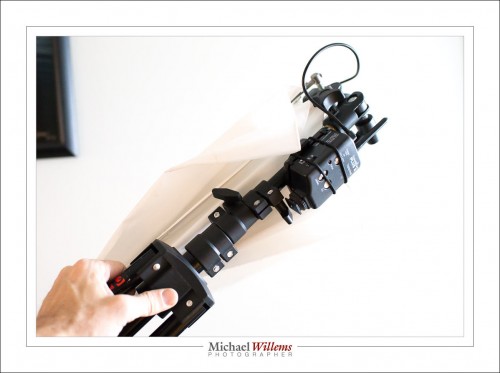

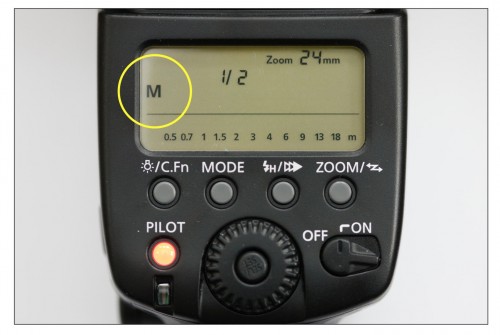

But there is a trick: HSS, or “Auto FP” flash. When using HSS, instead of flashing once, the flash goes FlashFlashFlashFlashFlashFlashFlashFlash very rapidly (at a rate of 30,000 times a second). This makes it into what is effectively a continuous light. As the narrow shutter slit travels down, the FlashFlashFlash keeps going on and hence the flash illuminates the sensor gradually.

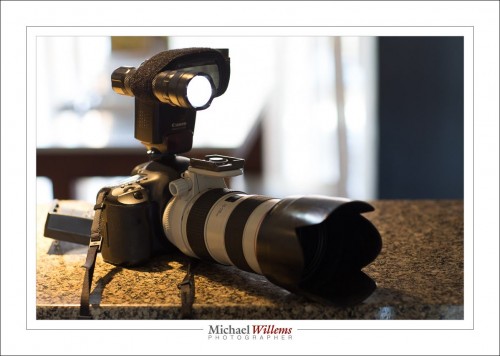

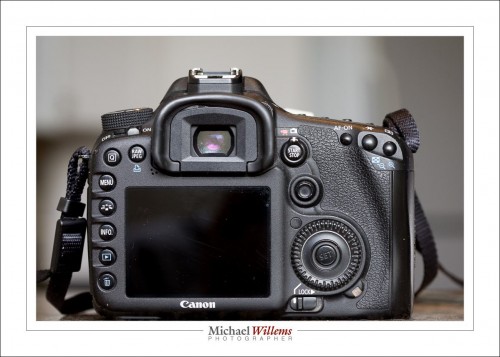

So, set your camera (Nikon: camera menu, select “Auto FP” flash sync) or flash (Canon: set flash to HSS symbol) to high speed and you are set to go. You can now use any shutter speed, up to whatever. 1/4000? Sure. Go for it.

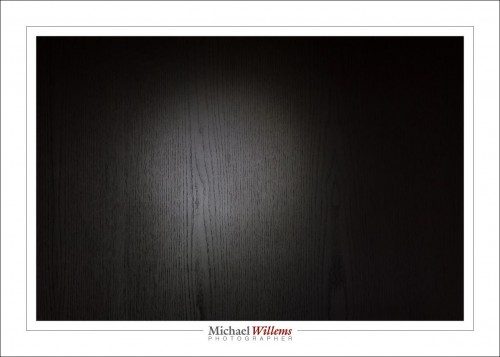

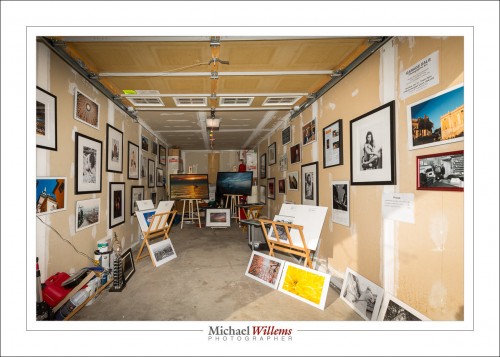

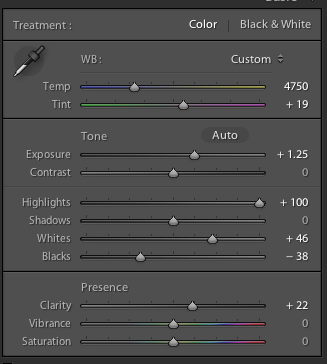

The problem? HSS loses most of your power (you are illuminating the closed part of the shutter, after all), so your flash range is reduced. At 400 ISO and f/8, my flash has the following maximum range:

- 1/30 sec: 9m

- 1/60 sec: 9m

- 1/125 sec: 9m

- 1/250 sec: 9m

- 1/500 sec: 3m

- 1/1000 sec: 2m

- 1/2000 sec: 1.5m

- 1/4000 sec: 1m

- 1/8000 sec: 0.7

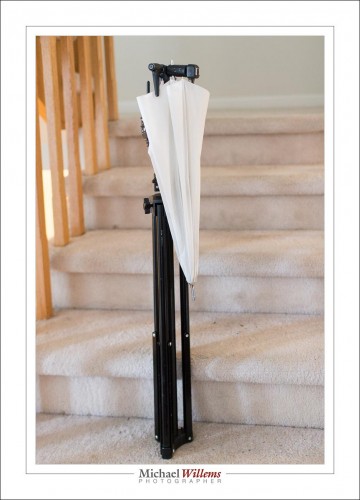

So up to 1/250, varying the shutter speed, as you would expect, has no effect. But then HSS kicks in, and the range starts to drop dramatically. At 1/8000 sec, my flash, at full power, only reaches 70cm (about 2 ft). And if you are using a modifier, like an umbrella, forget that: you would be lucky to get a few inches.

So while HSS is a great idea, it is not very useful in most practical situations. Because you are most likely to need to need it when it is bright outside, but that’s also when you need most power and cannot afford to lose any. Catch-22, since HSS steals from Peter to pay Paul. Now you know.

Math buff note: can you see any math logic in the numbers above? Yes, every stop faster shutter speed loses you the square root of 2 (roughly 1.4) in available range. So, two stops faster shutter means half the range.