Can you ever use a flash aimed directly at the subject? I mean.. the victim?

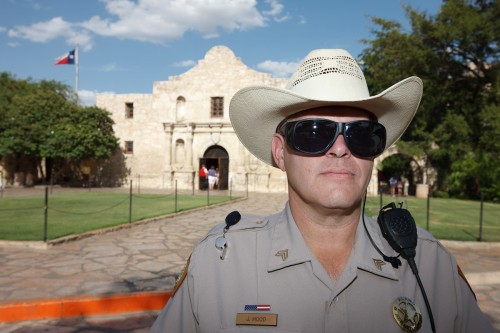

Yes. Outdoors, you can do this. Look at this shot from a recent softball shot:

To do an outdoors shot like this on a summer day (it is the first day of summer on the northern hemisphere, after all):

- Ensure the subject is not in direct light – sun behind them if possible.

- Go to the maximum shutter speed when using flash (1/250th sec on most cameras). If the light is fairly constant, I am assuming you are using manual mode, as a pro or someone who wants to shoot like the pros.

- Find a nice background.

- Now set the aperture for the correct background (around -1 stop on the meter perhaps). This was around f/5.6 at 100 ISO in the shot above.

- Then turn on the flash and shoot – with the flash aimed directly at the subject of you cannot bounce.

- Use flash compensation if you need (if the subject is too bright or too dark).

The awful “direct flash” effects are minimised by the available ambient light filling in the shadows: your flash is now the “key light” and the ambient light is the “fill light”, which fills in the shadows left by your flash.

Result: an OK picture even though you are not using modifiers like umbrellas. Yes, these would be even better but you can’t always use them.