Here’s another opportunity to learn from me. If the five-day workshop at The Niagara School of Imaging at Brock University in August is too long for you, or if you want to learn basics or need a refreshes on both simpler and more advanced subjects, then attend my series of three hour seminars at Pro store Vistek in Mississauga!

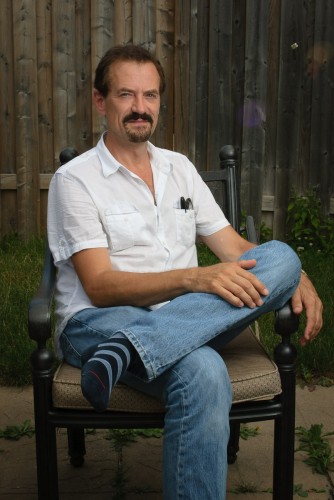

To give you an idea of the kind of skills you can gain, here is an image taken of me yesterday by my Sheridan College student George Kartken – great job.

Want to learn how to do this type of thing? Join me in my courses. Starting within a couple of weeks, these are a great opportunity to learn a lot in a very short time. Space is limited: see the list, and sign up, here.