HDR, or “High Dynamic Range” is a digital technique that squeezes together two or more images that were taken with different exposure settings, and then take, if you will, “the best from each one” and combine those.

At issue is the dynamic range in an image, which can exceed what your camera can handle. “Dynamic Range” means the difference in stops between the darkest and the brightest areas. On a sunny day with dark shadows and bright sunlight this simply cannot be handled by your camera: either the darkest areas are exposed properly, or the brightest areas, but not both.

HDR solves that: you take one image with the darkest areas well exposed, one with the lightest areas well exposed, and perhaps one or more in between, and then magically combine them, using software like Adobe Photoshop, which has HDR functions built in, or market leader Photomatix.

Problem solved: the entire image is now well exposed, dark areas as well as bright areas. In essence, the software reduces the dynamic range; we call this tone mapping.

“Artistic” HDR—More than using HDR to solve dynamic range problems, you can use it to give pictures a strange, hyper-real, otherworldly look. This is very popular.

It is also very risky, I think, for several reasons.

One is that the novelty wears off very quickly. Initially, the first time you see such an HDR, you think “WOW!” in capitals. But a little while later, you shrug, and say “oh, yet another HDR image, yawn”. In the future, we will say “oh, HDR special effects… that’s so early 21st century”.

The second reason is that when you do this kind of HDR, you are not really a photographer, but rather, a graphic artist. That is fine, but do realize that this is what is happening: you are getting praise for something you did not do (great photography), and for something that wasn’t actually there (unless you were taking LSD). Nature simply does not look the way that “obvious HDR” makes it look.

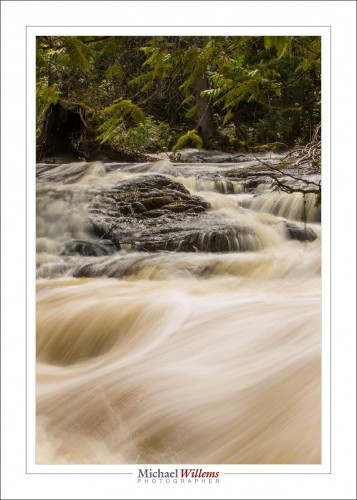

But that is my personal opinion. By all means play with art effect HDR (I have, too), and by all means produce some works of art this way. Just don’t do it for every image you produce forthwith. Now, an example of that kind of HDR. Deliberately overdone and bad:

Ouch!