Following up from the “printing” post, I want to give you a little perspective on print pricing. Both for the buyers (companies and individuals) and for the sellers (the photographers and artists).

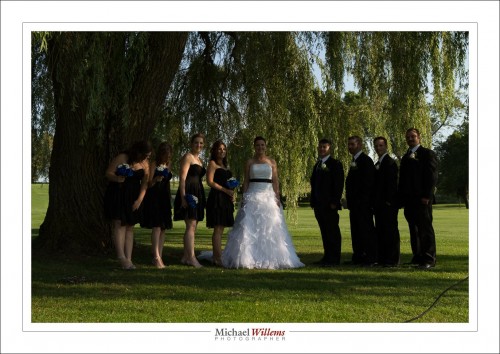

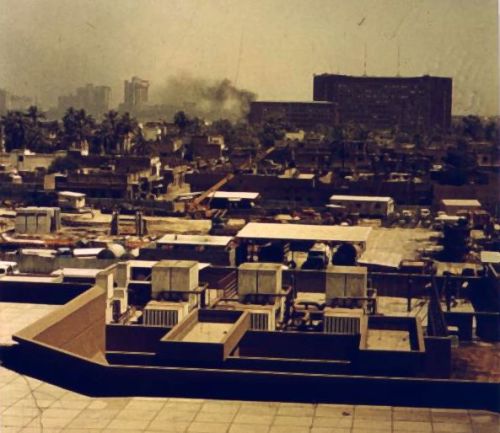

Professional art prints cost money. To give you an idea, a professionally made image printed on 13×19” paper, ready to frame, will cost $249. A 13×19” print framed ia $536 (you see two in the picture below). And a 40”x24” (approx.) metallic print, framed: $1435. (that’s the one on the left).

“Why? I can make a print for $20, surely?”, is an objection I have heard many times.

Well, no – that is not the way to look at this. And there are three ways to understand this. I thought it might be useful to go over those, today.

One way is by analogy. Sure, the print may not cost the sale price. But that is like saying “I went to the law office and I got my will done. I’ve got it here: it’s a piece of paper made by an HP printer, typed by a secretary. The paper and the typist time are no more than $15, so why should I pay more?”. Or perhaps it is like saying “Rembrandt’s brushes, canvas and paints cost him 2 florins, so that is what I’ll pay for that Rembrandt painting over there”. You see the silliness of those ways of looking at it, presumably. Printed photographs are the same. They are, in a term I have heard recently, “high-end wall furniture”. Any furniture designed for you and sold in limited numbers (“we’ll only make 20 of these couches”) will be worth money. And more than the cost of wood and cloth, of course, if we stay with the analogies.

The other way to understand is by looking what goes into a print. A framed art photograph for your wall contains, of course, a lot more than the paper and ink (just as the will contains more than just the paper and ink):

First, it contains, if you will, “intellectual property”:

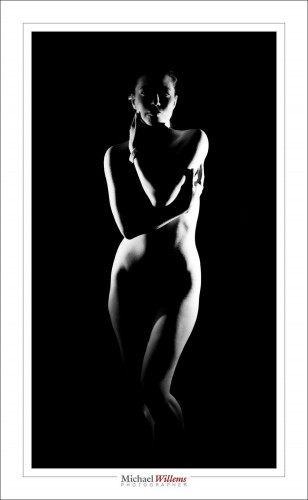

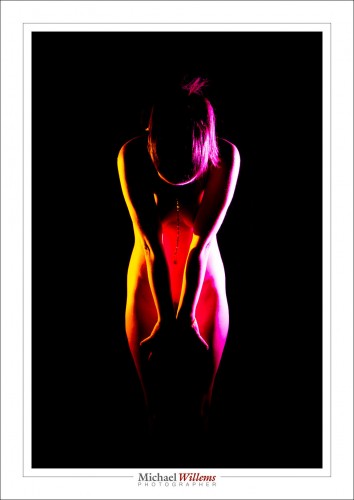

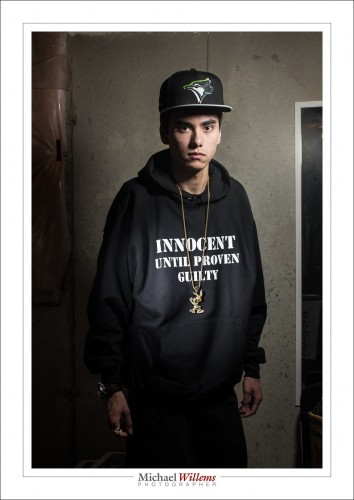

- Most importantly, the artistic taste, vision and ability that led to the image.

- The photographic expertise. It takes 10,000 hours to become an expert at anything, and that is certainly true for artistic photography. You pay the lawyer for his experience and ability to deliver; same for the artist.

- The printing expertise. Any idea how long it takes to become good at printing with the right colours, contracts, and so on, and to create prints on the right kind of paper, and prints that last?

A story, probably apocryphal, has it that Pablo Picasso was sketching in the park when a woman approached him. “It’s you — Picasso, the great artist! Oh, you must sketch my portrait! I insist.” So Picasso agreed to sketch her. After studying her for a moment, he used a single pencil stroke to create her portrait. He handed the woman his work of art. “It’s perfect!” she gushed. “You managed to capture my essence with one stroke, in one moment. Thank you! How much do I owe you?” “Five thousand dollars,” the artist replied. “But, what?” the woman sputtered. “How could you want so much money for this picture? It only took you a second to draw it!” To which Picasso responded, “Madame, it took me my entire life.”

Second, the photograph contains “real cost”. That is, of course, not your problem if you are buying, but it is nevertheless perhaps illuminating to see that there’s a lot that goes into a wall photo:

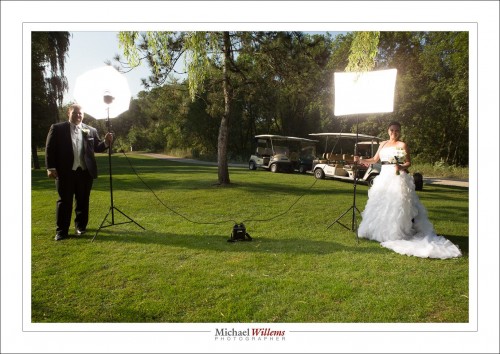

- Proper photographic equipment – at last $20,000 is needed to have a proper photographic setup. And that’s really just the cameras and lenses. Yes, proper equipment is important. When you blow up that image, imperfections due to cheap cameras and lenses will be noticed.

- Printer and computer equipment. Again, this is not cheap. You cannot expect permanent prints from a cheap inkjet printer or from a Costco machine. Proper printers have ten inks, not just one or two; and they are pigments, not dyes. The computer equipment, software, disk space, etc also cost money, and proper high-end calibrated screens are essential.

- Supplies. Proper art paper and pigment inks are not cheap. My printer has 10 cartridges for the different colours, and it seems that every three minutes one of them is out. And they cost $22 each. And the paper: $50 will buy you a small box – and again, they’re constantly out.

- Time. The time to make the photo in the first place. But also, the time to finish that photo. And then the time to print. It takes two minutes to even feed a sheet of paper into a pro printer, and that’s without the printing having started yet!

- The frame. Handmade frames and custom-cut mats are a real cost. Go to an art supply store and ask to have something framed and you will see.

- Time to put it all together. By the time you see a work of wall art, the artist has made the photo, set up the equipment, finished the photo, made the print, driven back and forth to buy inks and paper, driven back and forth to have the photo framed or wrapped, and so on.

So buyer: while it may not be your problem that a lot of real cost goes into wall art, I think it may be enlightening to realize exactly how much. Your artist is not getting rich over your back. And seller: when you do the math, on a simple spreadsheet, you see it is not viable to sell for less than “standard pricing”, unless you want to work for less than minimum wage, of course. Importantly, both buyer and seller should realize there is real, true, value in a piece of wall art.

And finally, the third way to understand print pricing: a product’s value is defined by its scarcity. This is, presumably, interesting to any buyer! And this is why we tend to print in limited editions. You can go pick up a piece of wall art at Ikea, but apart from the cheap printing and eventual fading, more importantly, approximately 8 million other homes or offices will have the exact same print. And that’s just in your town.

So yeah, you want the same Amsterdam canal pic that families from Toronto to Trondheim, from Stockholm to Singapore, from Israel to India have in their living room? Go ahead, here it is:

But if you want something unique, that not everyone else has, that is handmade, autographed, and produced in limited editions, then you may want to come to me and other wall art makers. That’s real value added to your environment.

What’s more: I can produce this image at any size you like, on any paper you like, with any frame you like. To fit you, instead of you having to fit the print.

So – head on over to www.michaelsmuse.com and similar sites, or go visit a gallery, and buy your own unique wall art. Now you know it’s worth it!