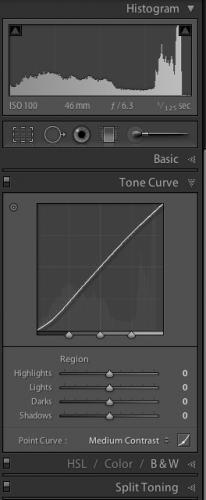

In Adobe Lightroom, the organizing/editing app of choice for most pros, you can use (and hence, see) a lot of panes full of functions to the left or to the right of the image or images you are looking at. In Develop module, these panes include Basic, Tone Curve, HSL, Detail, and so on; each pane with its own set of functions.

All those panes can result in a long list of functions: one that can be impossible to get a quick overview of.

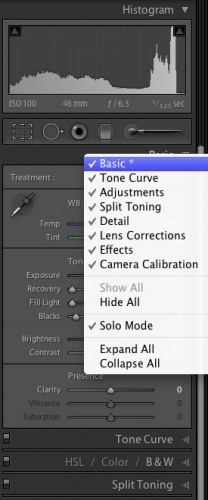

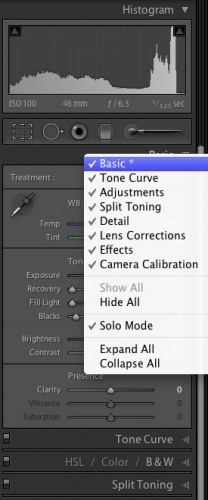

And that is why we have “Solo” mode. Right click on any pane’s name, as for instance I am doing here on the “BASIC” pane in the DEVELOP module:

And as you see, there is an option called “Solo Mode”. Turn that on, and from now on only one pane opens at a time in that module.

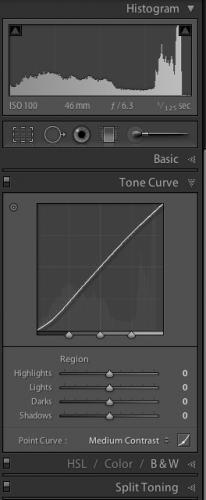

So if for instance I click on the “Tone Curve” pane, the Basic pane and any other panes that are open, instantly close.

This makes Lightroom much easier to use.

Note, you only need to turn this on once, but you need to to it on each side (left and right) in each module (Library, Develop, Print, etc).

There are of course many more shortcuts and nice-to-knows: Michael does photographer coaching, both remotely and in person on location: contact me if you are interested.