If you are shooting with a digital camera, your camera may give you the option to shoot in JPG format or in RAW format. All SLRs have this option; many compact camera do, too. Check the menu.

Why shoot RAW? It has drawbacks!

- A RAW file is three times larger than a JPG, so fewer images will save on your card, and it will take longer to download them. And you will need more hard disk space.

- A RAW file is in a camera-maker’s proprietary format and you may need extra software installed to read it. You cannot take it into the camera store for a print unless you first convert it to JPG.

Yes, true.

But it also has advantages, which greatly outweigh the drawbacks.

First, a RAW file contains much more information about light than the JPG that you will eventually make from it. That is a key part of your understanding: eventually, a JPG file will be generated. If doing this in camera, this means that the image is processed a certain way by your camera. While if you do it later, on your computer, then if you have under- or over-exposed a RAW image, for instance, you can “fix” it before you make that JPG.

And second: When a JPG is made, many settings are applied. Settings like:

- Should it be a colour or black and white image?

- How much sharpening should be applied?

- How much extra saturation should be applied?

- How much extra contrast should be applied?

- What white balance should be applied?

- What colour space should the JPG be encoded in, sRGB or AdobeRGB?

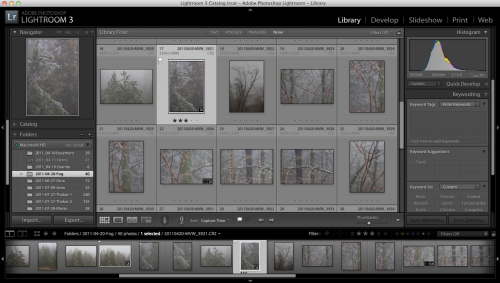

Believe it or not, you have settings in your camera for all of the above, so whether you are aware of it or not, whenever you take a picture, you are always making all these decisions. And if you are making a JPG in the camera, all these settings are applied to the image. So they are final. While a RAW file also contains your settings, but only as suggestions, and all the original data is part of the file. So if you want to change your mind: no problem. One click in Lightroom, Aperture, Photoshop, or whatever software your camera maker gave you, and you can change any of these settings, without any loss of quality.

So if you set your camera to black and white and you create a JPG, not all the king’s horses, or all the king’s men can bring the colours together again. But if instaed you shot RAW, one click and bingo, colour is back.

That is why I only shoot RAW images, ever.

“But it’s extra work, Michael!”

No it isn’t! IF your exposure and all the above settings were all correct in the camera, your software will follow them and create the right JPG for you – correct first time. No extra work.

It’s only extra work if you choose to not set it all while shooting. I often don’t worry about white balance while shooting, for instance, since it saves me time while shooting – one click later at home will set the white balance. So in choose to not spend time worrying unduly about white balance while shooting, so I can concentrate on composing. That’s a choice!

SO if you are not yet shooting RAW images: you should be. Unless all your camera settings are all correct whenever you shoot. In that case, hats off to you, and carry on with JPGs!