As you make more and more photos, backups become more and more important. And of course you make them. Right?

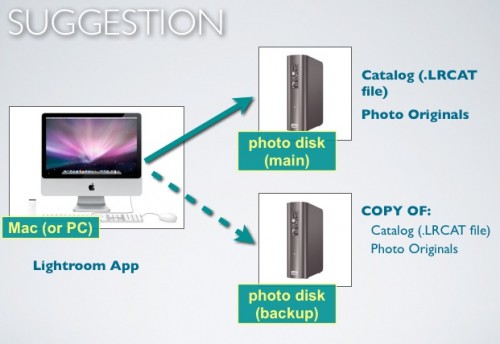

This is what I do:

Details:

- My photos live on a 3 TB external drive. When I add photos from a camera, they go there immediately, not to my Mac. Straight onto the external drive!

- My Lightroom catalog also lives on that external drive – that way, I can take that drive to anyone with Lightroom installed and I have all my work right there!

- When I am happy that the pictures and catalog are good, and ONLY then, I “intelligently” copy the new stuff to a second 3TB drive. I do that only once I am convinced it is good – no sense writing bad data. The script for that intelligent copy is here (link). Intelligent means the script checks all files on both disks, and copies over the differences (anything new gets added to the backup disk; anything deleted gets deleted from the backup disk also).

- I do not reformat the memory card until after this is done and verified!

- I also back up my regular Mac, using standard backup software – but since I keep little data on that mac, it’s not critical.

OK, so I am pretty well backed up.

Except I am not. All my data lives on the two drives attached to my iMac. That is very dangerous – many things can go wrong. Things like:

- Lightning

- Flooding

- Fires

- Burglary (you think the burglar would take only external disk 1 and leave the backup drive behind?)

- …and more, too much to imagine.

To solve this, there’s a few things not to do:

- I could back up to DVD drives, but that is very expensive, very slow, and very unreliable. Ditto for CDs.

- Cloud backup – too early to be practical (making a full backup at today’s Internet network speeds would take months – literally).

- Keep memory cards – way too expensive.

- Drobo – this is a possibility (RADI drive), but the Drobo uses its own proprietary encryption.

So here’s the solution:

- Instead of more local backup, I use a third 3TB drive, and once a week everything gets copied to that third drive (again, using an “intelligent” script).

- And the key: this third drive lives off-site, not at my home studio! So come earthquakes, lightning, or floods, I’m OK.

- Finally, I have one more set of off-site drives, per year, which I make a full copy to at the end of each year.

A lot of work. But worth it, because I can sleep. Are your memories (or your business) worth less? I didn’t think so – so come up with an off-site storage strategy today!