Well, not in 8 years. Here’s a technical note in the form of a post from October 2009 that is still valid…:

A reminder to all flash photographers: you need your shutter speed to be below the camera’s flash synch speed.

What does this mean? Let me explain.

The flash fires for the briefest period, of course. Like 1/2000th of a second. That is why we call it a flash.

So when it fires, if the light is to reach the entire film or sensor, the shutter needs to be totally open at that point.

That much is obvious. But what is not obvious is that there is an engineering limitation in your shutter. Beyond a certain shutter speed, the camera’s synch speed, the shutter never totally opens. Instead, a small (increasingly narrow) slit travels across the shutter to give each pixel a brief exposure time.That’s cool – the shutter does not have to be super-fast and expensive and you get a fast shutter speed.

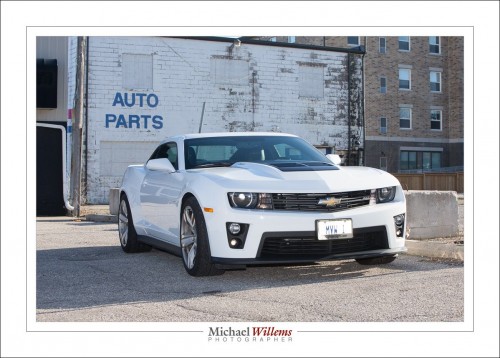

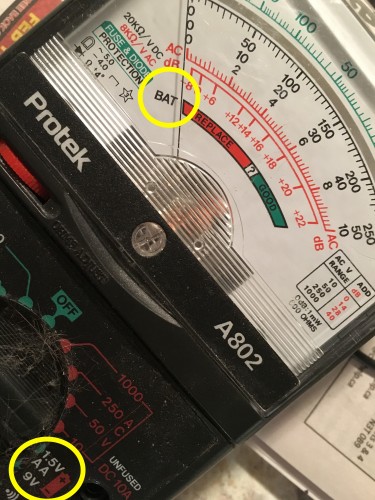

But this gets in the way when you are using flash. When you fire during those short exposure times (on most modern cameras, faster than about 1/200th second), the light does not reach the entire sensor. Look at this example I shot to illustrate this, at speeds from 1/200th to 1/1000th sec:

You can see that as I exceed the sync speed, the light only reaches part of the shutter.

You should also note that especially when using external flashes with Pocketwizards or similar, flash takes time to set up. My 1Ds MKIII has a synch speed f 1/25oth second but as you see, at that speed it is already beginning to cut off. Best stay a bit below your synch speed (I typically set my shutter, when I am using studio flash, to 1/125th second).

(There is a way to overcome that: fast flash, which some high end flash units offer. This continuously, all the time that the shutter travels, pulses the flash at a very rapid rate, so that the slit, as it travels across the sensor, has light coming in throughout its travel time. It works great – do use it when taking flash images outside – but it uses a lot of energy, and hence decreases the range of your flash.)

(Advanced tip: I know of at least one photographer who uses this effect to introduce an electronic version of a neutral density filter or a barn door: he sets his camera to 1/320th second while using flash, and turns the camera upside down. That makes the top part of the image dark, at least as far as the flash part of the light is concerned!)