Once again, military technology is at the basis of what we do with technology. It is incredible what humans will do in order to more efficiently fight other humans.

In the early 20th century an Austrian army captain named Scheimpflug worked out how to handle perspective in aerial photographs (this would come in handy in WWI, no doubt). Hauptmann Scheimpflug is famous for explaining what we know as the Scheimpflug principle. If you like math, look it up on Wikipedia. I warn you, it took me a while to get my head around all those formulas.

What do they do for us? They tell us how to use tilt-shift lenses (or view cameras) to change the plane of focus.

And I will give you a simplified version of its implications here today (yes, it’s simplified: no need to start pointing that out). I am talking about tilting here today, not about shifting. But even simplified, this is an advanced article that assumes you already know at least the basics of what tilt-shift lenses do.

I wrote this because I usually see people with tilt-shift lenses just wildly change every adjustment randomly: and that is not at all a way to guarantee results. Knowing stuff is always better.

WHAT TILT-SHIFT LENSES CAN DO

A tilt-shift lens (its tilting, specifically) allows you to shift the plane of focus so that you can make sharp not “stuff parallel to the sensor” (like the wall in front of you), but “stuff at an angle to the sensor” (like the floor below you).

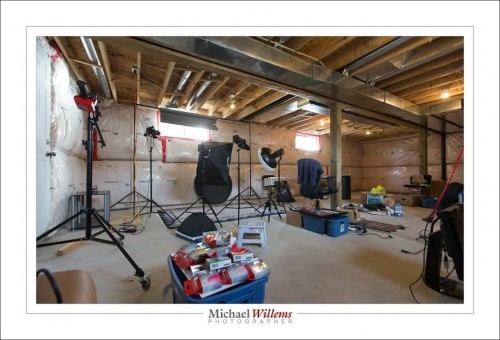

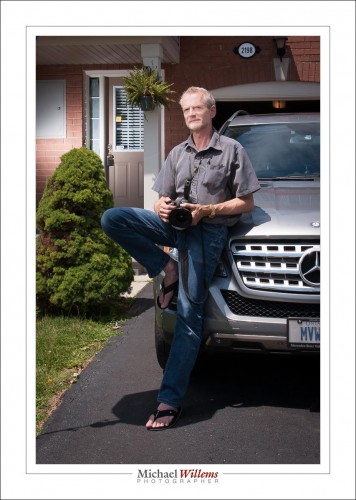

Consider this, the normal situation. With my 45mm lens set to f/2.8, I focus on the door, so it is in focus (but the stuff close to me is not):

Or I focus on the stuff closest to me, so it is sharp (but the door is not):

And if I want both in focus, well, I would have to go to a very small aperture (maybe f/16 or even smaller) to get them both sharp. Or to a wider angle lens, or I would have to move way back. None of which may be practical, or even possible.

Enter the tilt-shift lens. If I…

- tilt the lens down by the the right angle; and

- hold my camera at the right angle; and

- am at the right distance from the floor; and

- focus at the right distance…

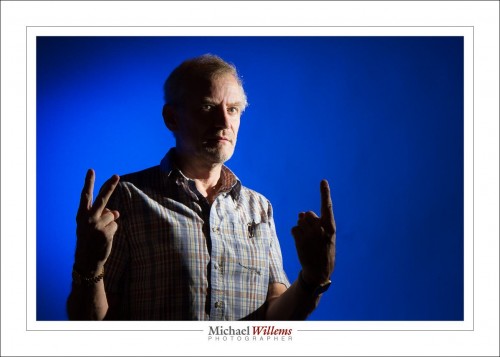

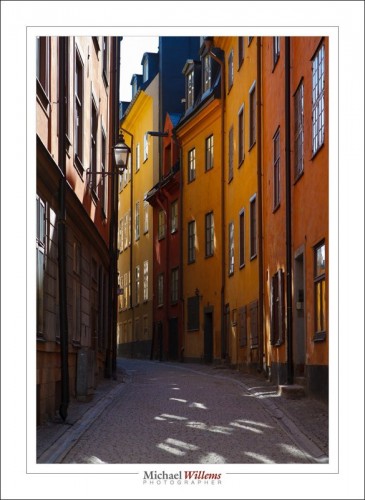

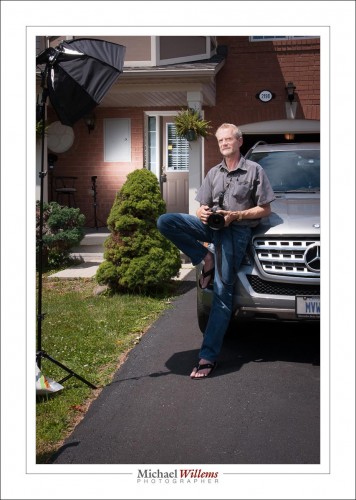

(I told you this was complex), then I can do anything I like. Like this:

The floor is in focus, from close to far. And yet I am still just at f/2.8!

So far, so good. The question is: once you have a tilt-shift lens, how do you focus it where you want? With the number of variables I just mentioned, there’s just about infinite possibilities, and very few of those actually work for you.

LET’S SIMPLIFY!

I like simplifying. So let’s start with taking variables out. Let’s hold the camera parallel to the floor (i.e. aiming straight ahead, not up or down) and set the focus to infinity. Then the focal plane (“where it’s sharp”) will be perpendicular to the sensor, and since we are holding the camera straight, that means it will be the floor – provided we get the height of the camera above the floor and the angle of tilt down right. Just two things!

And the relationship between them is given by a simple relationship:

J = f/sin θ

Where:

- J is the distance to the focal plane (“the floor”)

- f is the focal length of the lens (45mm in my case)

- θ (theta) is the angle at which you tilt the lens down (down, because the floor is below you).

My 45mm lens can shift down up to 8 degrees. So the relationship between angle and “how high you have to be above the floor if you want the floor to be in focus” is:

45mm T/S LENS

TILT ANGLE (deg) – DISTANCE (mm)

- 1° 2,578 (=2.57m)

- 2° 1,289 (=1.29m)

- 3° 860 (=86cm)

- 4° 645 (=65cm)

- 5° 516 (=52cm)

- 6° 431 (=43cm)

- 7° 369 (=37cm)

- 8° 323 (=32cm)

Remember, this is with the camera pointed straight ahead, and the focus set to infinity. (Why this is so is easily derived from the formulas in the Wikipedia articles and basic knowledge, but I will spare you the math, except to mention that that the tangent of 90 degrees is infinity).

So in my last image, I was about 85cm above the floor, with the lens angled down by 3 degrees. Bingo.

(A tilt-shift pens is hard to adjust very finely: the adjustments are very precise. Patience is needed.)

An alternate way to use this simple rule is to start with what you want. I.e. “if I am x distance away from the floor (and pointing straight ahead with my focus set to infinity), what should my angle be?)

The formula is simply the same as above, so it becomes:

θ = sin-1 (f/J)

So if I want my camera to be, say, 1.7m above the ground, I would have to angle down by sin-1 (a.k.a. arcsin) (45/1700), which my calculator says is 1.52 degrees. Yes, a scientific calculator is handy. Or you could work these out once and carry a little table with you, like this:

45mm T/S lens

DISTANCE (m) – TILT ANGLE (deg)

- 5m 0.5°

- 4m 0.7°

- 3m 0.9°

- 2m 1.3°

- 1.5m 1.7°

- 1m 2.6°

- 0.5m 5.2°

NOW WE GET A LITTLE MORE COMPLEX

Now let’s let go of the assumptions, namely that you focus on infinity and point straight ahead.

When you alter the focus setting of your lens (i.e. you do not focus on infinity), the focal plane swings up and down. It still starts below your camera at a distance given by the formula at the top, but now it is not parallel to the horizon. As you focus closer, it swings up (or you swing the camera down, whichever you prefer):

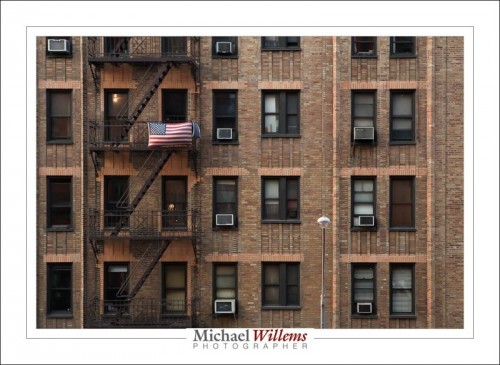

Scheimpflug Intersection (Source: Wikimedia)

By how much? I.e. what focus setting will give you what angle?

Aha, glad you asked. Another formula!

From Wikipedia:

ψ = tan-1 ( (u’/f) sin θ)

Where:

- ψ (psi) = the angle that the focal plane angles up by;

- u’ = the distance along the line of sight from the centre of the lens to the PoF (i.e. the distance to the focal plane; i.e. the focus setting, since you will be focusing on your plane of focus);

- f = your lens’s focal length;

- θ = the angle you have tilted the lens down by.

So that means that while at infinity focus the plane is perpendicular to the sensor, as you focus closer, the plane tilts up.

IN PRACTICE

So now.. knowing all this, in practice, this is what you would do if you want a particular focal plane to be sharp:

- Determine how far away from the intended focal plane you will be. E.g. if the intended focal plane is the ground, say in a landscape shot, then you may say “the sensor will be 1 metre above the ground”.

- Put the camera on a tripod at that distance from the ground.

- Aim it straight ahead (the sensor is vertical).

- Set the focus to infinity.

- Now, using the tilt-shift mechanism, tilt the lens toward the intended focal plane (e.g. down, in this example) by the angle given by θ = sin-1 (f/J) above, so in our example, with a 45mm lens and 1m distance above the floor, that means angle down by 2.6 degrees.

Alternately:

- Aim the camera straight ahead (the sensor is vertical).

- Set the focus to infinity.

- Now, using the tilt-shift mechanism, tilt the lens toward the intended focal plane until you see it sharp.

Both these ways to get to the same result give you a sharp ground (if that is what you are intending). The first method is less error-prone, of course; calculating angles rather than trial and error is always recommended if you can.

Not perpendicular?

And if the focal plane should not be perpendicular to your sensor, e.g. because the landscape slopes up, or because you wish to aim down at an angle, then start as in the first method above; then (after aiming down if need be*) and simply adjust focus closer than infinity until the plane tilts up to where you want it.

(*) If you aim the camera down, of course the actual distance between it and the intended focal plane increases, so you will have to lessen the tilt angle.

Did I mention this was a little complicated?

Disclaimers: Any errors here are mine. And as said, of course I am simplifying a little here. If we were to be totally accurate, we would take into account the different distances between lens and focal plane on the one hand (hinge rule) and sensor and focal plane on the other hand (Scheimpflug rule); and the fact that a T/S lens on an SLR does not rotate around its axis, but instead, rotates up or down in its entirety; and the fact that a lens is not a simple single-element idealized lens (lens plane versus lens front focal plane). But what I discuss in this article will do entirely well enough in practice.

___

American friends: why am I using metric instead of feet etc, you may ask? Read what The Oatmeal says, and no more words necessary.