As you all know, the inverse square law states that light gets weaker in proportion to the square of the distance.

So at twice the distance I get one fourth of the light. At three times the distance, one ninth of the light. And so on.

Good. So if I aim a flash at an object at one metre and get good exposure at f/5.6, then at two metres distance I expect two stops less light, i.e. f/2.8, two stops more open (i.e. 4x more light).

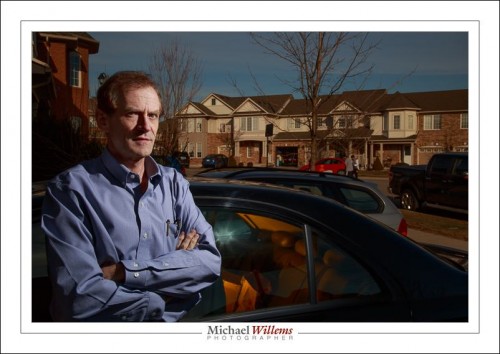

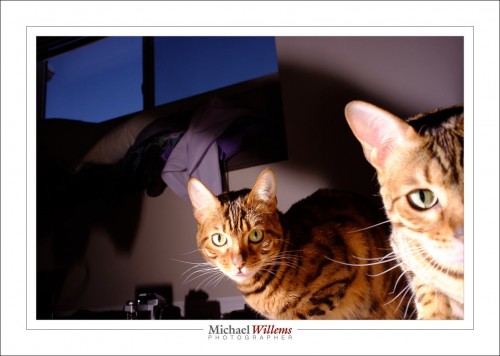

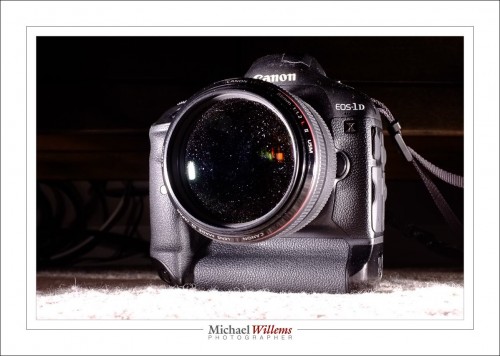

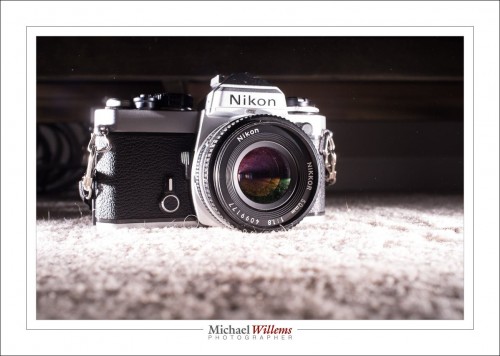

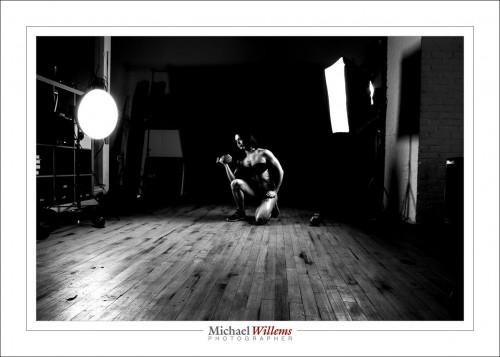

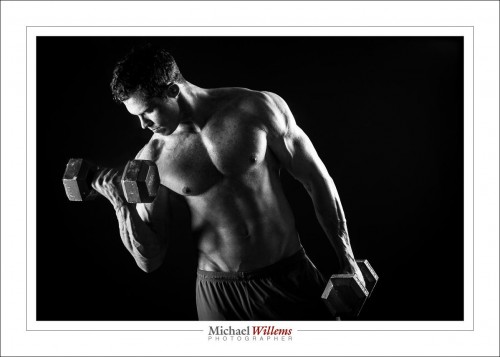

Let’s see. First, let’s use an LED flash light. At f/5.6:

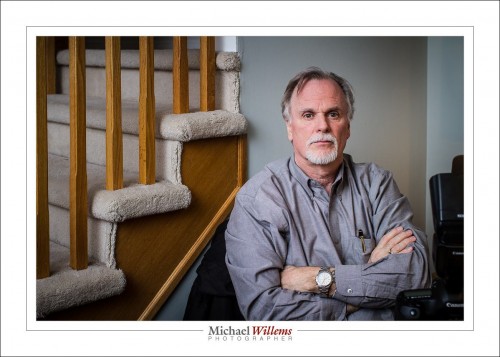

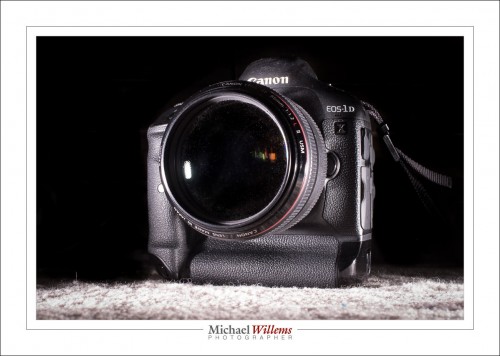

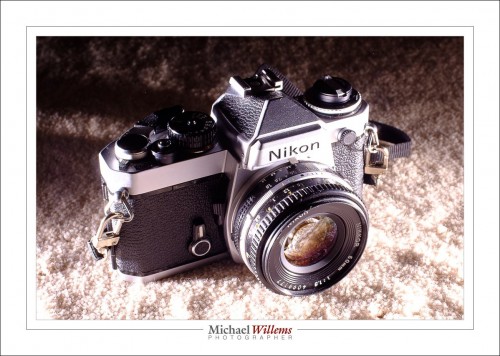

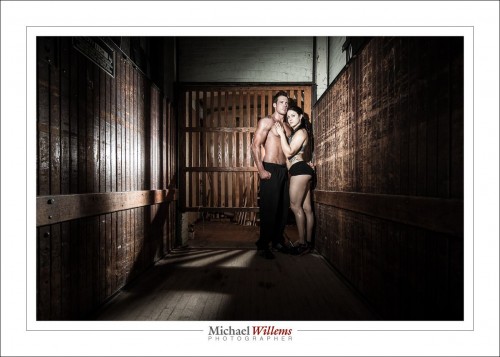

Now when I move from 1m to 2m and make the aperture f/2.8, it should be equally bright:

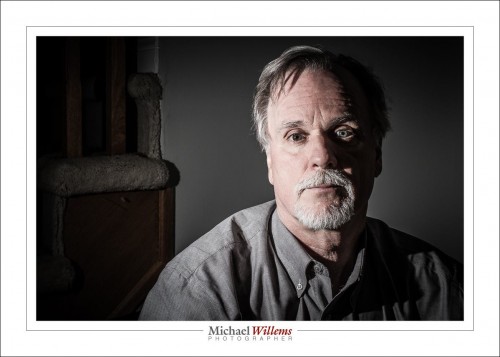

What gives? It’s brighter! Only by reducing the exposure 0.5 stops do I get to the same brightness (as verified with the histogram, and looking only at the lit part):

So it seems that the inverse square law does not hold!

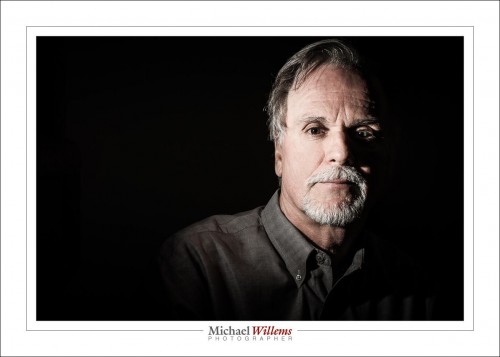

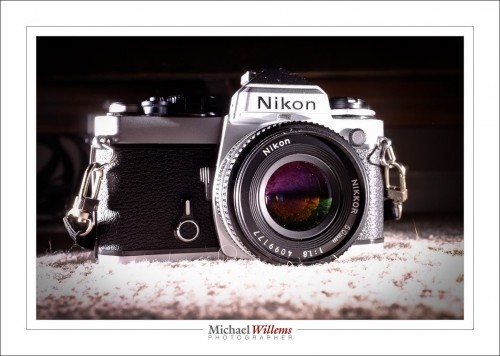

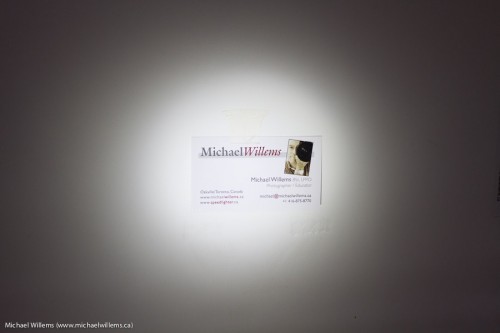

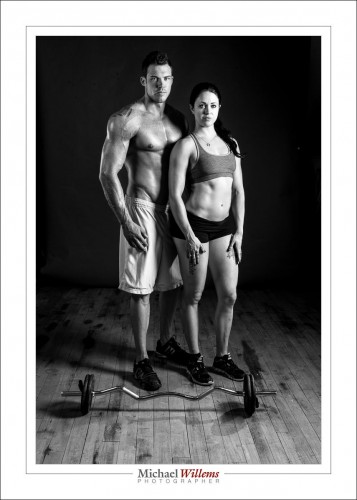

Here’s another example. I will shoot at 1m, 1.4m, and 2m. If the first shot is at f/8, the second one should be at f/5.6 (half the light, because 1.4 squared is 2), and the third f/4 (a quarter of the light, because 2 squared is 4). When I do that, I get:

Hard to see here, but they get brighter each time, while theory says they should stay the same.

Only by reducing the second picture by 0.25 stops, and the third picture by 0.5 stops, do I get the same exposure. So my flash apparently needs to be corrected by -0.25 stops per stop.

Wait. Is this crazy Mr Willems saying the Inverse Square Law is incorrect?

Yes. Yes, he is. I am. I am saying exactly that. The Inverse Square Law does not apply. Not to concentrated beams. The Inverse Square Law applies only to point sources of light that radiate that light evenly in all directions. When we move the light away from the subject, the angle loses us photons, but the moment we “catch” some of these lost photons and send them to the object we are lighting anyway—and that is exactly what we are doing with a concentrated beam—that moment, the law no longer holds. Yes, the light gets weaker, but by a smaller amount. That smaller amount, the “escaping photon recapture rate”, or “EPR rate” if you like silly acronyms, is +0.25 stop per stop lost, in the case of my Canon flash.

So what would affect the numbers?

Clearly, at the extreme end, with a laser beam, the correction is virtually +1 stop per stop lost (think about it: how else could we do moonbounce, where we bounce a laser off the surface of the moon). Meaning, the light does not go down at all with distance. With a flash light, it is, as you see, a little less extreme: there is dropoff; just a little less than you would expect. With a large softbox that radiates in all directions, you will get something closer to the inverse Square Law. With an umbrella, you get closer to it still.

But this is not a theoretical discussion, of interest only to geeks. This is important in practice to us photographers. If I move a snooted hair light twice as far away from the subjects it is lighting I should get two stops less light (2 squared = 4). But the light reduces less than that. So instead of going, say, from f/8 to f/4, I might need to go from f/8 to, say, f/5.

My advice: Learn how the light sources you use (straight flash, bounced flash, umbrella, softbox, etc) behave when you double the distance. Do this in the dark, so ambient light plays no role. Easy enough, and then you have an idea that will be valuable in real-life practice.

Check out my e-books on http://learning.photography/collections/books and learn everything I know. Taught in a logical fashion, these extensive e-books (PDFs with 100-200 pages each) will help you get up to scratch quickly with all the latest techniques. And when combined with a few hours’ private coaching, in person or via Google Hangouts, you have no idea of the places you’ll go. You’ll be a pro!