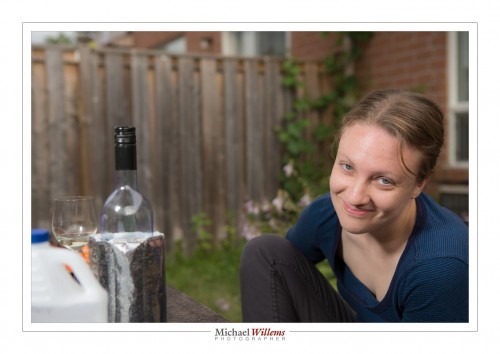

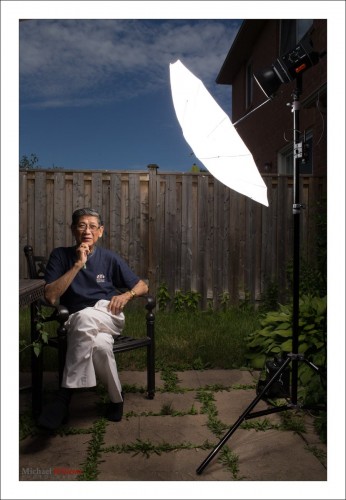

You can take nice pictures in the back yard. Like this one of yesterday:

To do this, you need:

- An SLR camera with manual mode.

- Off-camera flash: e.g. a remote flash in TTL mode fired by your camera’s pop-up, for many cameras, or by a 580EX/600EX/SB-900/etc on the camera; or a remote flash in manual mode fired with Pocketwizards.

- Perhaps a modifier, like an umbrella or a small softbox.

- A light stand and bracket to mount all the above.

So the equipment is relatively simple. And the use? Not so difficult either. Let me repeat how you do this.

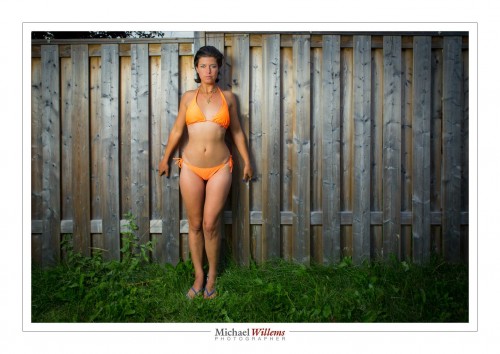

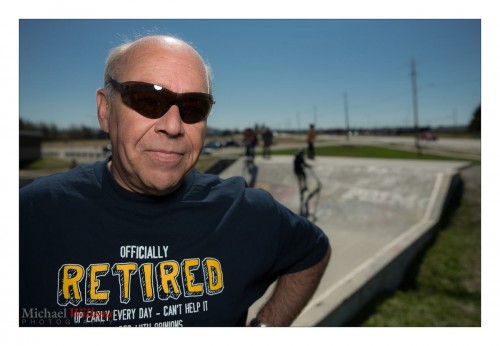

First we set the exposure of ambient part of the image (the “background”):

- Camera on MANUAL mode

- ISO: Set to 100 ISO

- Shutter: Set to 1/250th sec

- Aperture: Start at f/5.6 if it is overcast. Or if it is brighter, go up to f/8, f/11, even f/16. Trial and error can work: you simply go as high as you need to get a darker background (for instance, on a sunny day, f/5.6 or f./8 will give you a way too bright background). For me, a “darker” background is -2 stops. If you like less drama, -1 stop is OK.

That’s the background done.

What about the foreground?

If the aperture you need to get to a darker background is f/8 or a smaller number, and your flash is close to the subject, you can probably use an umbrella or softbox. If it is f/11 or higher number, you will possibly need to use direct flash, unmodified, since a modifier loses power.

All I did was add a little vignetting and some minor tweaking.

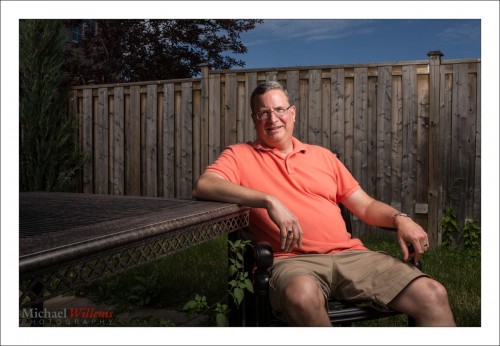

Easy once you get the hang of this. And I can help in many ways. One of those ways: Aug 18-22 you get the chance to learn from me in a very intensive 5-day workshop at the annual Niagara School of Imaging, held at Brock University. There are still a few spots open: book now if you dig flash as much as I do.