When you determine exposure for a photo, the principle is simple: only three things make a photo brighter, assuming everything else remains the same (which is the case when you are in manual mode, so this is how you should learn):

- Higher ISO

- Larger aperture

- Slower shutter

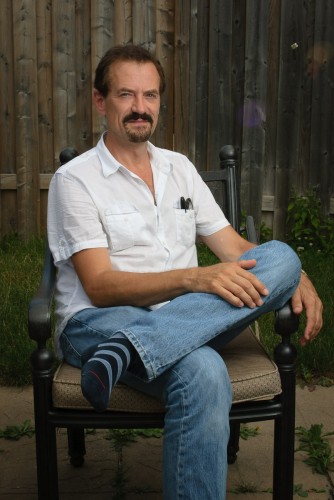

So it should be simple to get a beautiful darker background like this one here, in a recent picture – taken two weeks ago of one of my Sheridan College students:

It is simple – once you realize a few things.

Darker or Lighter? It may not be obvious to you whether you want the background lighter or darker. In fact darker brings out (saturates) the colour, but you may think brighter is better. Your great advantage is that you have a digital camera, and each click costs $0, so the best thing I can advise you: practice.

What About The Foreground? You may need different light for the foreground. Here, I used an off-camera flash into an umbrella. My advice is: worry about the background (the ambient light) first, as above; then worry about where you may have to add light. One thing at a time!

But where do I start? You will soon get a feeling of what settings are in the “acceptable range”. One thing you could do, as a sort of training wheels, is set your camera to P (Program mode); see what ISO/Aperture/shutter settings the camera would suggest, and then use those as starting points in your manual settings. But soon, you will get to know what you want:

- for motion (blurring or freezing), shutter is your first thought

- for depth of field, aperture is your first thought

- for quality, ISO is your first thought

And you will then have only two other variables to worry about. Combine that with ISO starting points (200 outdoors, 400 indoors, 800 in difficult light) and you have only one to worry about.

Learn The Limits. Learn what aperture will give you too-shallow DOF (e.g. f/1.4 when you are 2 inches away), What aperture will give you fuzziness (eg f/45). What shutter speed will give you motion blur (slower then 1 divided by the lens length). And so on!

Put all those together, and exposure becomes much easier. The key: reduce everything to the above very simple principles.

Exercise: this week, shoot only in manual mode. Both inside and outside, so you have big changes to deal with, This is the best way to handle learning exposure, and once you know exposure, photography becomes much easier.