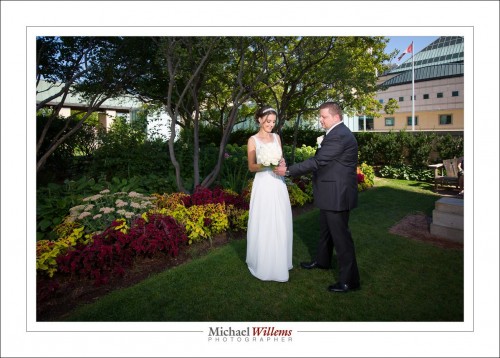

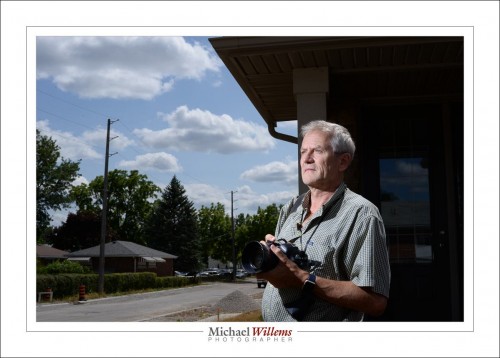

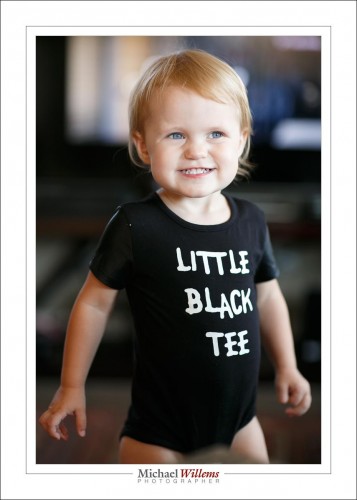

..In real life, you only have so much time when shooting an event. So you need to be quick, and you need to really master a bunch of little things.

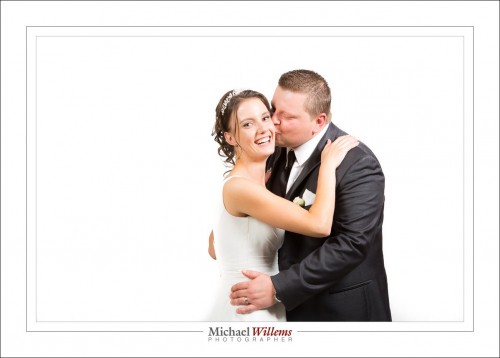

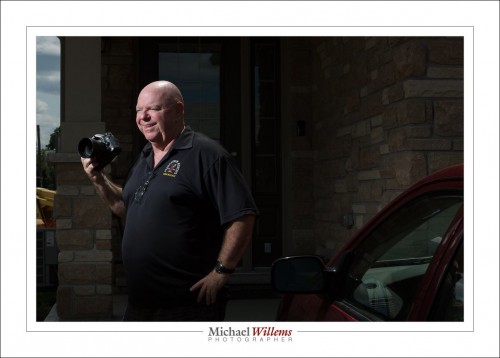

Take this picture, taken with a wide angle 16-35mm lens at 800 ISO, 1/40 sec, f/4, with bounce flash aimed behind me. . Attentive readers may recognize the Willems 400/40/4 formula in that, modified slightly (800 ISO instead of 400) because it was so non-reflective.

Nice, but why are the verticals tilted inwards toward each other at the top?

Because the photographer was aiming the camera upward! That results in this tilt.

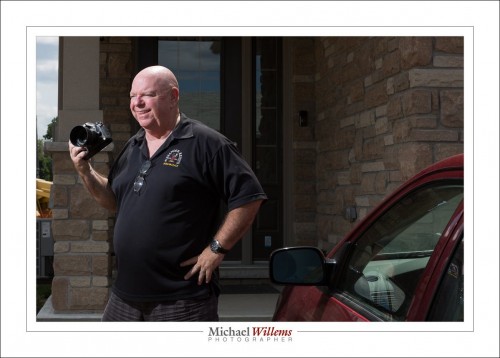

If the camera had been pointing downward, you would have seen this instead:

And it is only if the photographer aims the camera straight ahead, parallel to the horizon, that we get the proper picture:

And now a little secret: that one, the third, was in fact the actual photo taken by the photographer, Because the photographer, and that was me, knows to hold the camera parallel to the horizon. Check the verticals before you click!

So how did I create the other versions? Simple, by using TRANSFORM in Lightroom. And just like I can make a good picture bad, I can make a bad picture good.

So why not just shoot as you like and fix them all later? Mainly because this takes that most valuable of all commodities, time.

So. Last question. Flash you say. Really? How do I know this isn’t just ambient light?

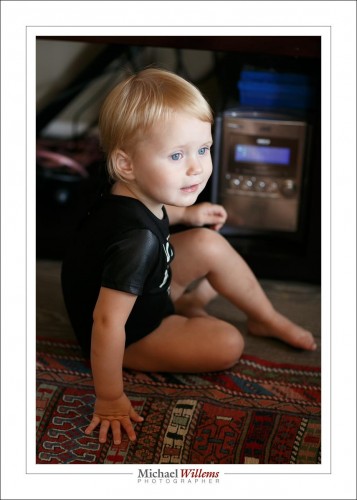

Well, let’s take one with the flash OFF. Here we go:

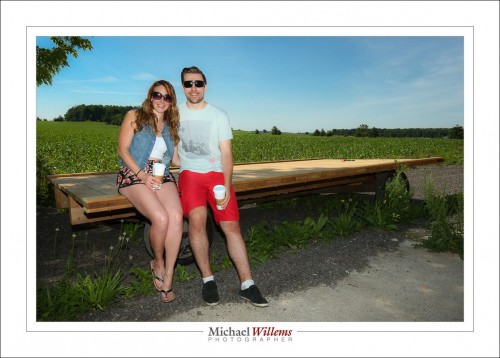

Now, we could have used ambient like this but just increase the exposure by three stops. That is true (higher ISO, lower f-number, and/or slower shutter). But then two things would happen: a) you would notice the drawbacks of those actions (e.g. more motion blur, less depth of field, more grain), and b) the picture would lose its magic. You would get this:

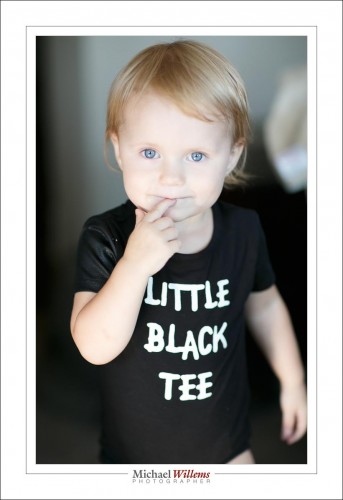

Well, de gustibus non est disputandum, but I prefer mine:

Isn’t this “creative” stuff fun?

Want to learn from me in person? 5 hours in Brantford, Ontario, on Sunday Oct 2. With a maximum of 5 students. Sign up tonight and save big: