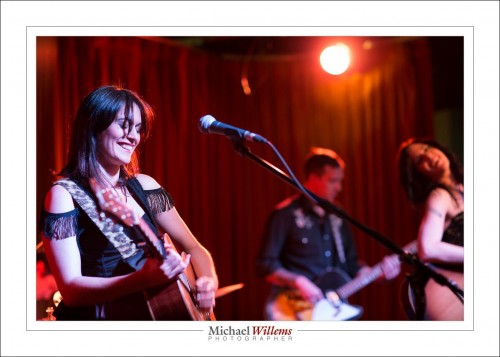

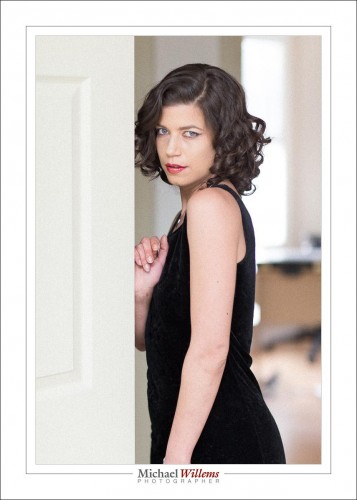

Last week I shot Scarlett Jane at a gig they did in Toronto:

That shot prompts me to say a few things.

First, the moment. “If it smiles, shoot it”: the mood is captured well by this moment. Moments are important. Look for them, wait for them, grab them!

Then the light. It was pretty light at the venue, but that is relative. Light is not really light: I used an 85mm f/1.2 lens set to 1/80 sec at f/2.0, ISO 3200. Fortunately, my camera, a 1Dx, allows that.

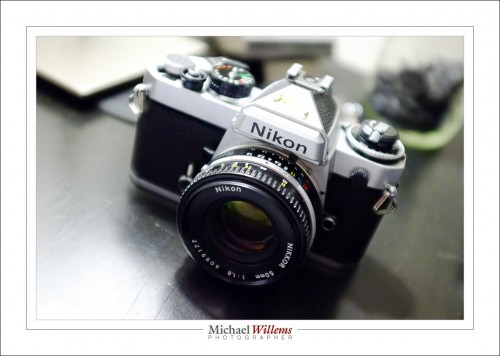

But I found the primes almost impossible to focus. Most shots were way out., whether I focused using one AF point, or manually. My experience is that focus on digital cameras is tough in the dark. So I shot most of the rest with f/2.8 zoom lenses like the 70-200.

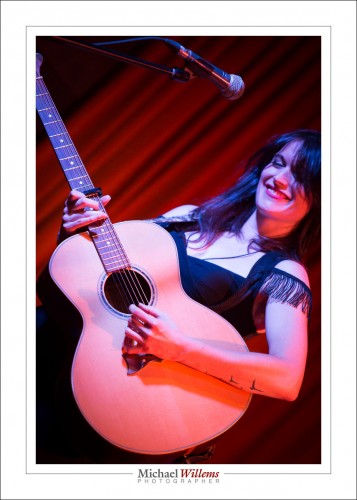

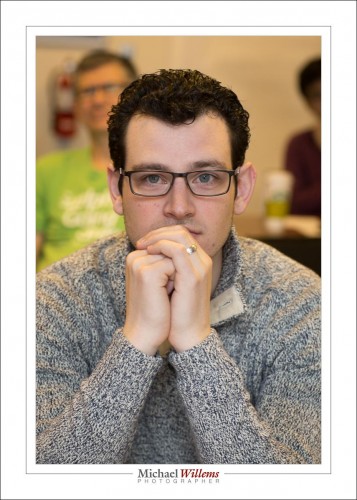

Here, a couple more:

..and again, as you see, the quality is good (here it’s 1/60th at f/2.8, ISO3200), but the moment, the mood, is most important. And these ladies had fun!

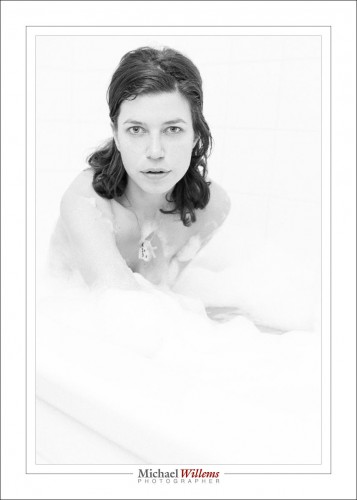

OK… one more to prove the point.