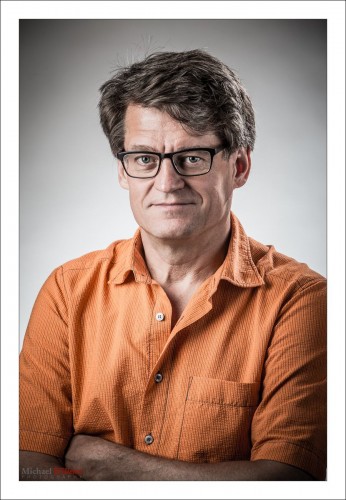

Food.. food… food. Few pleasures in life as good, and blogger Rhonda of professional Toronto-area food blog http://oliveandruby.com/ knows this well, and makes it her mission to share her food insights, knowledge and recipes with the world. If you like food, this is a recommended blog.

But Rhonda is not only a food expert: she is a wonderful person, and she is very intelligent to boot. It all shows in her blog.

And in her photos. This year, Rhonda has been spending some time with me to hone her skills in food photography. How else to convey the quality of food but by great photos?

It’s not just necessary – it is also fun. Food photography is fun because it includes all of the following:

- Composition insight.

- Technical camera skills.

- Technical flash skills.

- Knowledge of flash modifiers.

- Light skills.

- Storytelling.

- Post-production skills.

- Planning.

- Improvising.

- Studio photography.

So while it seems simple (“prime lens… aim… click”), it is far from that. It’s pretty much “if you can shoot food, you are a pro”… and not even all pros can shoot food.

But Rhonda can. Look at the excellent work she produced today, under my guidance and with my feedback. First, a pro photo of her Jerk chicken:

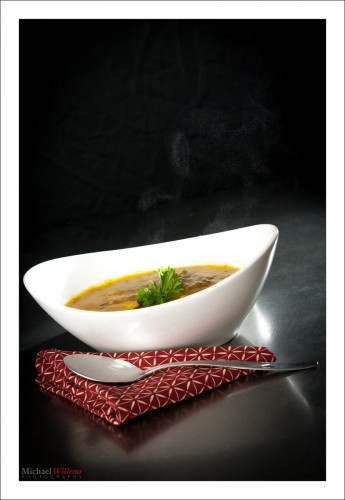

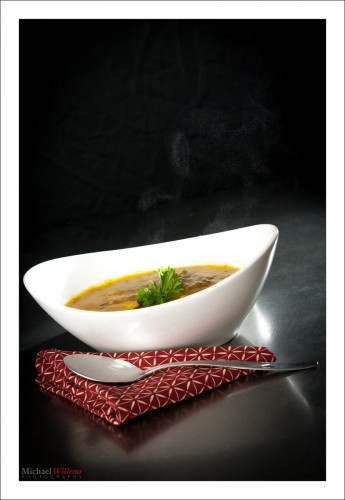

…and then, a pro photo of her excellent soup. Look carefully, you will see that even some of the steam is included:

These compositions did not come out of nowhere. First, of course, Rhonda spent forever (that’s my careful estimate) cooking the food.

And then the compositions. They started with, first, a full discussion of the work she had done to date. Photo critique (not criticism: critique!) is a fantastic way to learn, which is why I like to take an hour or so as part of these types of lessons to do just that. People know their own answers if they ask their own questions. Questions like: “how could I have made this even better?”, and “is every element of this image supporting the story?”.

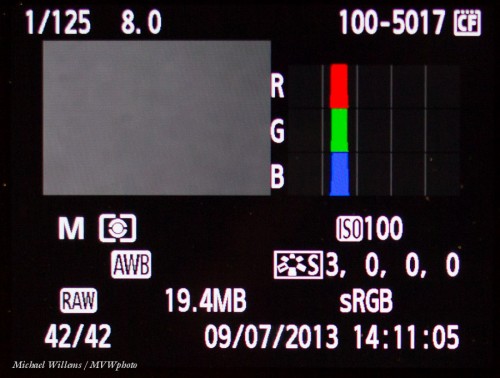

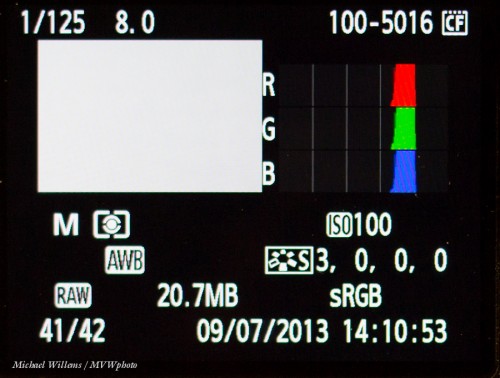

Critiquing and shooting in one session together is also a great way to learn because you discuss, and often debate, every decision made. Why is that flash there, not here? Why is that flash at quarter power, not half? Why aim forward, not backward? What do we do to see the steam? Why f/4 one time, and f/16 the next time? How does a light meter work?

These decisions involve some complex thinking, and there are many decisions to be made – in food photography, nothing is accidental. It is good to discuss these points at length, and private coaching is a great way to do this.

My top ten tips for food photography are:

- Keep it simple. Ask “is every element in the picture needed?”.

- Think colour!

- Think light!

- Get close and fill the frame

- Decide what should be in sharp focus, and what need not be.

- Crop carefully: put a lot of thought into this.

- Keep it simple.

- Keep it simple.

- Keep it simple.

- Keep it simple!

The equipment? That was simple too, today. A Nikon D90 with a 60mm micro lens (a macro lens, to non-Nikonians) and two simple flashes; one bounced off a white ceiling, and one as a “slave cell” follower. And a tripod. A Honlphoto 12″ snoot. And Adobe Lightroom.

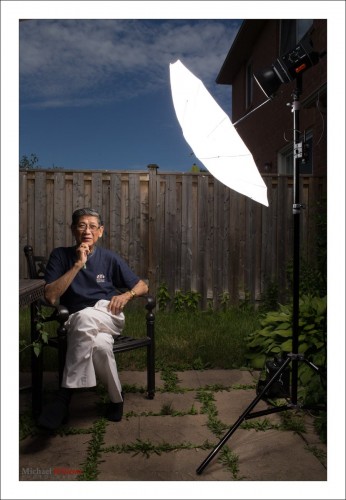

One of our setups

But it’s not just what you use – it’s how you use it. If you learn how to improvise, you can handle those pesky issues that will always, inevitably, crop up!

Like that steam. After the soup did not produce enough, we used two little cups of boiling water placed right behind the soup bowl. That, and a flash with a snoot behind the food aimed forward toward us, and a black background (as you see, a simple black reflector on a stand), and a setting that nixed all ambient light, and manual for all settings, camera as well as flash. Easy once you know.

Finally… from my perspective, the best part of food photography?

I get to eat the food.