There is a hidden world in water’s surface tension. A world like this:

Is that difficult to photograph? Depends on how much patience you have.

Here’s how I just took this picture:

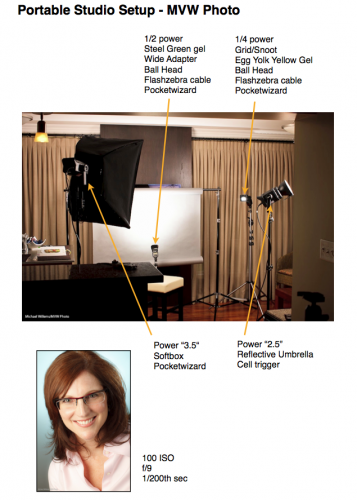

- Camera on a tripod, equipped with a suitable lens – I used a 100mm macro lens but a 50mm or a telephoto lens may also do.

- I set the camera to 320 ISO, f/11, 1/250th second.

- A black background, lit up with a gelled flash – or just a coloured background.

- A tray with water – also preferably black. I used a wok since I had nothing else, plus a wok is round, so you get circular waves.

- A plastic bag with water. I hung it from my microwave. Poke a very small hole in it with a pin.

- A for the background – I used a 430EX with a Pocketwizard driving it. The flash set to manual 1/4 power and equipped with a Rust gel from Honlphoto.

- Another flash aimed at the drops from the side. Also driven by a Pocketwizard, this flash was equipped with a Honl snoot. Also set to manual 1/4 power.

This looked like this:

See the ziplock stuck in my microwave door? And see the tripod on the right?

And given enough patience you will get pictures like the one above. Yes, patience is required – I just shot 500 pictures to get 10 great ones.

Gotchas to watch out for:

- Too big a hole will give you streams of water – not flattering. You want slow-moving, large drops. Small pin hole achieves this (else, wait until the pressure lessens).

- Like in any macro photo, you may need to clean up your picture to remove the dust you lit up with the flash.

- You will also want to crop the image.

- Watch for reflections of the waves in the bottom of the pan – shoot as horizontal as you can.

- Watch for reflections elsewhere too – I got a reflection in the side of the pan; some of this I had to remove in post-production.

- Focus manually; prefocus where the drops fall.

- You want fast flashes – and since a flash’s power is set by its duration, this means not full power, so make sure the flashes are close.

A few more samples: