For most photography, I recommend keeping post work to a minimum. Quick crop, perhaps a small exposure adjustment: done. For some types of photography, like press photography, adjustments of any other type are forbidden.

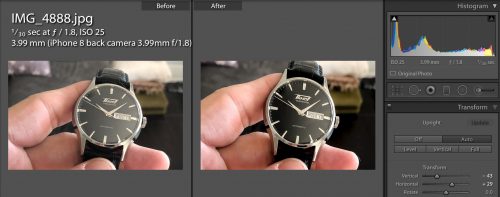

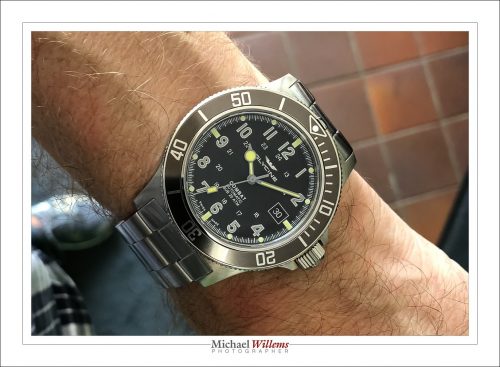

But for some, they’re necessary. Even an iPhone product shot like this, of my Glycine watch, needed some TLC:

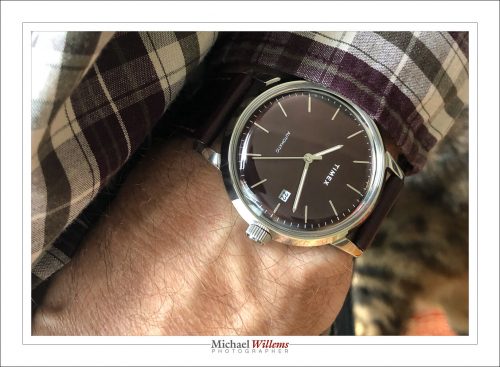

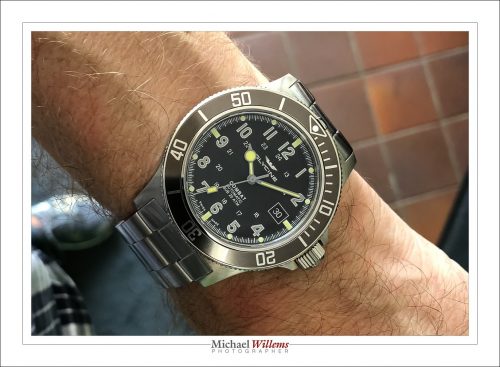

That’s one of my watches. Click on it to see the full version. And notice how perfect it looks. No dust at all, no smears or scratches, great contrast, and so on. All watches always look hyper-perfect in all ads.

And that’s because they’re hyper-edited. Things like focus stacking, and expensive editing.

In mine, above, I removed every speck of dust using the healing tool in Lightroom. Then I increased local clarity and decreased exposure on the watch face. I added a tad of sharpening and then noise reduction. And although small, the effects of these edits are important.

The good news: most of these edits are easily doable in Lightroom. For a commercial advert, you need Photoshop, but for everything else, Lightroom is fine.