“Shutter speed” isn’t all there is to shutter speed.

Uh oh. Michael is The Oracle. What on earth does he mean by that confusing statement?

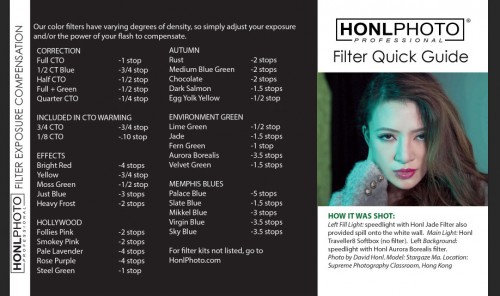

Well, let’s have a look. Let’s set up a couple of gelled and gridded speedlights (using Honlphoto grids and gels) and get a talented life model. Which is exactly what I did in August 2012 at Brock University, during the 5-day flash course I was teaching for the Niagara School of Imaging.

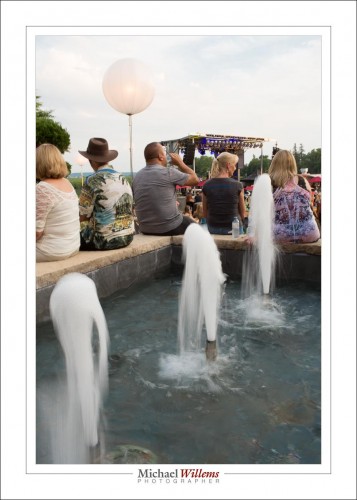

But wait. Because I want to show you the setup, let’s allow in some ambient light. To achieve this we use a really slow shutter speed, of 0.6 sec. More than half a second, in other words. That lets in some ambient. Not a lot, but enough to see the classroom, some of the equipment, and so on.

The picture, showing the setup with the two flashes, below. Look at the two little gelled speedlights, can you spot them? Purple gel on the left and yellow gel on the right:

OK. Great. Blurry as heck, of course: 0.6 seconds is ridiculously slow. Impossible to hold still. Right?

But wait. Lots of blur, yes, all over the picture, but look carefully. Click on the image to see it full size, and now look carefully at the model. What do you see?

She is sharp. No blur on her: she is tack sharp. There’s blur all over, but not much on the actual subject. A little “ghosting”, but she is substantially sharp.

But that’s impossible: the shutter speed was 0.6 seconds. So she must be blurry! Right?

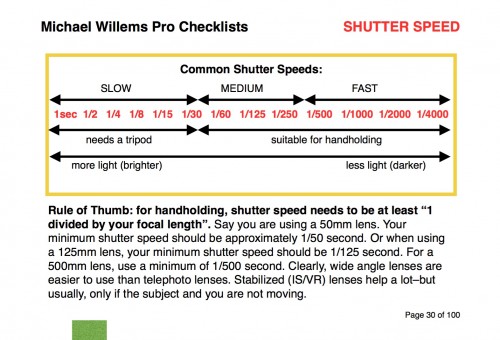

So that’s where I say “‘Shutter speed’ isn’t all there is to shutter speed”. The shutter speed may be 0.6 seconds, but the model is lit primarily (almost exclusively) by the flashes. And the flashes flash at 1/1000 second or faster. At 1/4 power, they flash for just 1/4000 second. So while the shutter speed may be 0.6 seconds, as long as the subject is lit only by the flashes, our effective shutter speed is 1/4000 second!

And that is why you see a sharp model: there is very little ambient light on her, so the effective shutter speed is determined almost exclusively by the flash speed. Which is very rapid.

So now let’s do a normal shutter speed, of 1/125 sec, so the ambient light is cut out. And here is the finished product:

So anyway. This is a studio shot. So I want no ambient light: the second picture, in other words. But when I shoot an event, like a wedding reception, I want to let in some ambient light to avoid those cold, black backgrounds. Instead, I want a nice warm background. To achieve that, I am happy to shoot with shutter speed as slow as 1/15 or 1/30 second. And now you know why I can get away with that.