“We have no budget for photography, but you’ll get credit!”. I have heard this many times, as I am sure all other photographers have, when a client is trying to get free photography.

It seems to me that there are a few problems with this: several reasons, in other words, to never engage in this type of free shoot.Let me explain.

One issue is the lack of perception of value. If, at a reception, say, it is taken for granted that the caterer, the waiters, the printer, the supplier of the flowers, the maker of the curtains, the electricity company, the people who supply the coffee and the barman all get paid but the photographer is expected to work for free, that means that the photographer is not perceived to be doing anything valuable. Would a waiter work “for credit”? No, and most of us would consider it insulting to even ask. If you are asked to do something that confirms the effort you are engaged in as having basically no value, I would argue that it is best not to do that.

Photography is not a thing

One reason for this absence of value perception is that photography is not a thing, and that furthermore there is a perception that the photographer does nothing but push a button. The Kodak perception: “anyone can do it”. Look online and see the advertisements offering to “teach you photography in ten minutes”. A staggering claim, and a sad one. Any photographer knows that ten thousand hours is more like it. But if the perception is that there is no value in pushing a button, and that that is all a photographer does, can you fight it?

No—but what you can do is look for value elsewhere. And that is in tangible objects. People like tangible things. My books on DVD are much easier to sell than my books as a download, for instance. So look for prints, albums, memory keys, possibly web sites, but as much as possible, things beyond just bits. Working ten hours for free is something you may be expected to do, but a large print costs money, and everyone understands this. It’s a thing, and things cost money.

I said several?

I said there were several reasons to not do unpaid work for credit. The second reason is that it simply does not work.

Quick: tell me the photo credit of the last 100 photos you saw.

So how many did you get? I would be surprised if you remembered any. “Photo credit” does not work. You will get nothing out of it.

I have heard many people promise me the world for doing free work. Unfortunately, I have never yet seen an iota of benefit out of all this crediting. So your name appears in a brochure, or under a picture on the newspaper. No-one notices. And if they do, it is because they are already your customer. But in no case will they buy more because of it.

Because building a brand takes time and effort. Name recognition, while a necessary component of a marketing approach, is not enough by itself. And even for that, name recognition, you need repeated mentions of your name, on and on, consistently, throughout multiple campaigns over time (yes, plural). One mention here and there is not going to do anything for you. Sure—there are exceptions to this. But generally speaking, your name being mentioned underneath a photo will do exactly nothing for your bottom line.

Never?

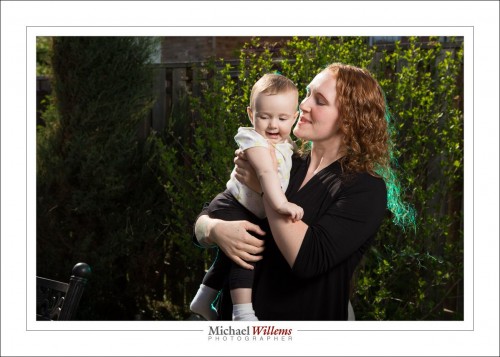

When I said “never”, I did not actually mean never. Of course if it is charity or if it is for a friend, you can do whatever free work you like. But in those cases you are not expecting a few mentions of your name to generate business.

So?

So, do not be afraid to ask for a reasonable fee for your work. I had a washing machine fixed yesterday. For a ten minute visit and a five dollar switch I paid $140 plus tax: $158. So do I need to feel embarrassed to ask for $125 an hour? Not in the least. Bankruptcy is not good for me, but it would not be good for my clients either. A business needs to be sustainable.And free work does not result in that sustainability, unfortunately., So next time you are asked to do work “for credit”, I suggest you respectfully decline.