Some photographers (like me, usually) prefer to use “back button focus”. That means that instead of focusing by pressing the shutter button half way down, they focus by pressing a button on the back of the camera. Usually the “AF-ON” or “*” (asterisk) button top right on a Canon camera like the one below. The shutter button now only operates the light meter (in manual mode) or sets the exposure (in automatic and semi-automatic modes.)

On most Nikon cameras, you can use the AE-L/AF-L button on the back to operate focus.

Why would you want to do this?

You might not, or you might. If you prefer this, it is probably for some of the following reasons:

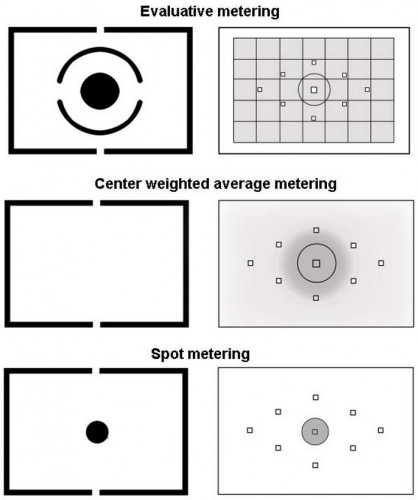

One is that it is easier to separate the process of determining and setting exposure from the process of determining and setting the correct focus distance. These are separate processes that have nothing to do with one another: why combine them into one button? You may well want to focus on the bride’s eyes, while taking an exposure reading off Uncle Fred’s grey suit. This way I set exposure and ignore focus. When I am done and exposure is good, then I go focus where the image should be sharp, and forget exposure (or vice versa). And the two areas do not need to be the same. And usually they are not the same. Unless, of course, your bride has 18% grey eyes.

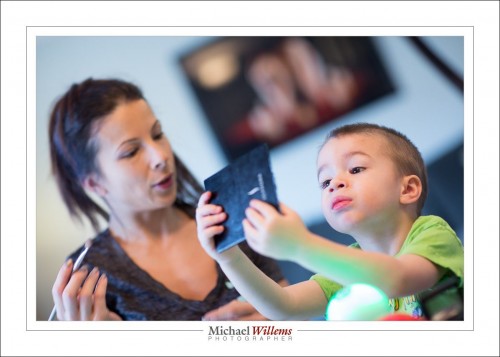

Also, it is easier to “set and forget” one or both. If, for instance, your distance to the subject does not change, why should you have to re-focus for every shot? There are plenty of situations where this is the case. Like portrait headshots. Focus once, then concentrate on expression and pose, not on focus. By using a separate button you make it possible to do this: focus once, and then forget it until you or the subject changes position.

The third advantage of focusing like this is that it is now easier to make manual adjustments. I focus using autofocus, but sometimes I want to adjust manually. No problem. I can do that, If my camera is set up for back button focus. Beep focus, then overrule that with manual focus.

How?

How do you set it? That depends on the camera. A few examples/notes:

- On most Canon cameras it’s a Custom Functions (C.Fn) entry or two. For instance, on the Rebel T3i you use C.Fn 9 (option 1 or 3).

- On the 60D, use C.Fn IV-1 (option 1, 2, 3, or 4)

- On my 5D Mark 3 it is done in the Custom Controls section of the Quick (“Q”) Menu: set Shutter Button Half-Press to “Metering Start”, and set AF ON to “Metering and AF Start”. I usually also set the AEL button (the asterisk) to “Metering and AF Start”. That way I can use either the asterisk or the AF-ON button. Less chance I miss it!

- Exactly the same applies to the Canon 7D.

- On Nikon cameras, set the AF-L/AE-L button to “AF ON”. To do this, go to the pencil menu, find section “controls”, and use “Assign AE-L/AF-L button.” Within this menu, choose “AF-On.”

Q: Michael, didn’t you say “back focus” was to be avoided?

A: Yes. But this is “back button focus”. A very different thing altogether. “Back focus” means the focus is inaccurate. “Back button focus” means that we are using a button on the back of the camera to start the focus process.

Q: So should I start using back button focus?

A: No, unless you understand all this, know your camera, and are happy to benefit from the advantages I outlines—and only if those are important to you. It’s no big deal either way; I go back and forth between using it and not using it. But now at least you know what it is all about.