Full-frame sensors have several advantages over smaller sensors:

- Full frame sensors have lower noise (better quality) than crop sensors with the same number of megapixels. This means they are better at high ISO values, where noise can become a problem, than crop sensors.

- The viewfinder is larger and brighter.

- You can achieve slightly blurrier backgrounds.

- Wide-angle lenses work as wide-angle lenses on a full-frame camera (as opposed to on a crop camera, where each lens works as though it were longer, compared to using the same lens on a full frame camera).

That’s a nice list, and it explains why most pros use full frame cameras, but there are also advantages to using slightly smaller sensors:

- They cost less.

- They are smaller, so cameras with a crop sensor can be slightly smaller.

- They can use special lenses (DX lenses for Nikon, EF-S lenses for Canon, etc) that were made especially for smaller crop sensors; these lenses are therefore smaller too, so they cost less and weigh less.41

- Lenses “appear to be longer” by the crop factor compared to the same lenses used on full frame cameras: this is obviously an advantage if you need a long lens, such as when shooting lions in Africa.

Drawback of these lenses: if you upgrade to full-frame, you need to replace your lenses.

Effect on Apparent Lens Length

As said, crop cameras “appear to lengthen a lens”. That is, a 35mm lens works like a 50mm lens when used on a crop camera; a 50mm lens works like an 80mm lens when used on a crop camera; a 200mm lens works like a 300mm lens when used on a crop camera, and so on.

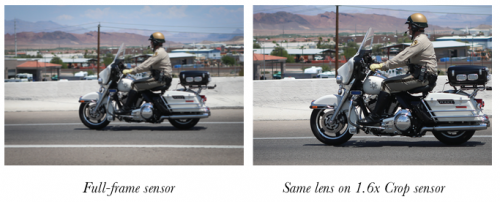

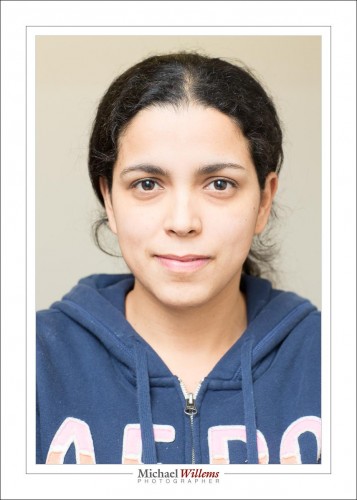

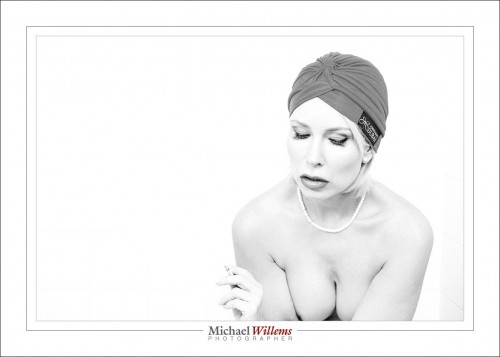

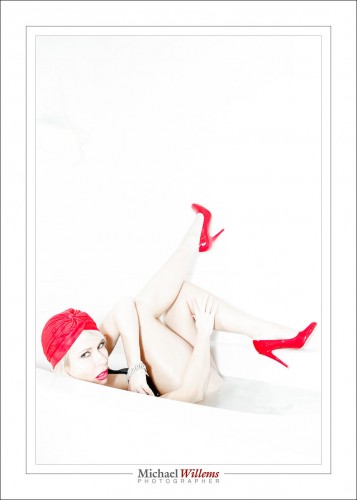

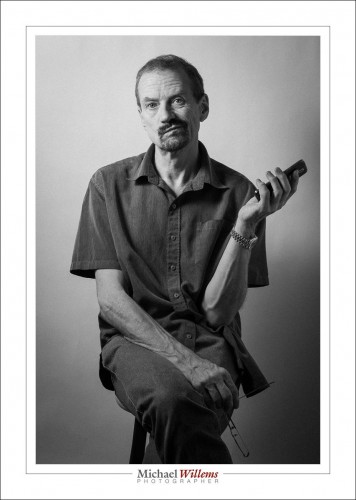

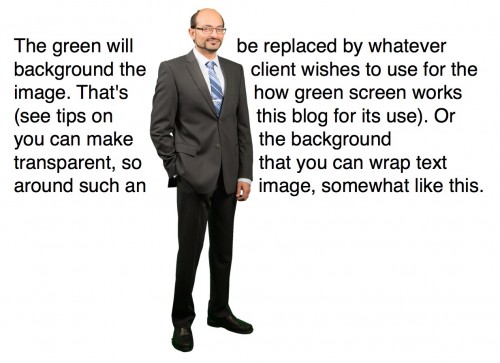

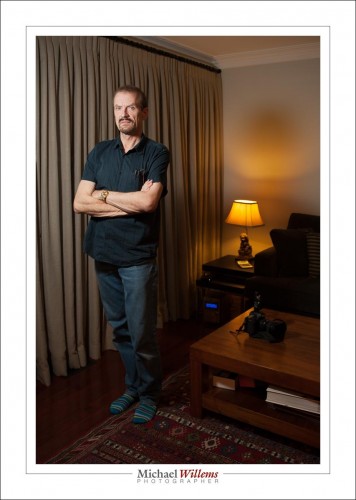

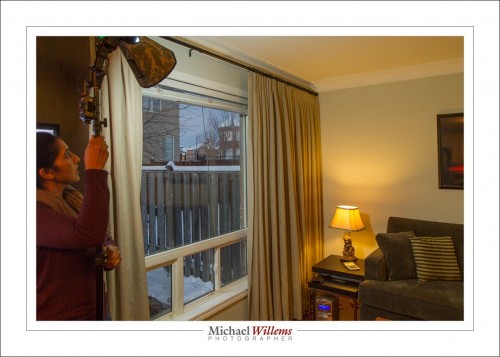

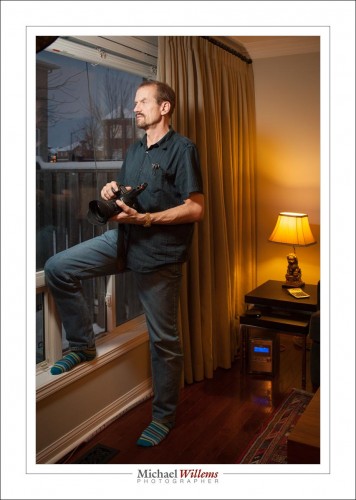

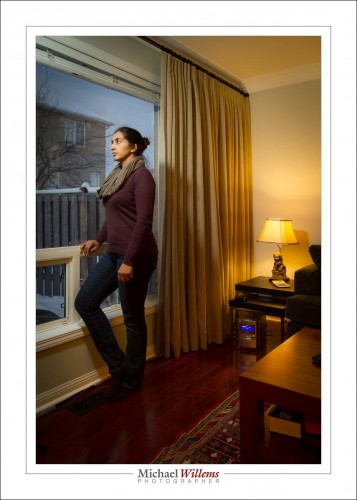

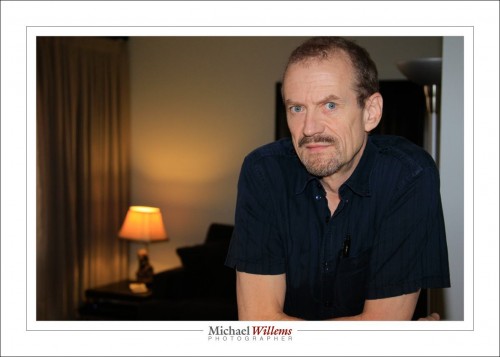

The same lens, for instance, mounted on two cameras with the same number of megapixels, one with a full-frame sensor and one with a crop sensor, might give these two images:

In this example, on the 1.6x crop sensor (the sensor that is 1.6x smaller than full frame), the same objects in the resulting image would be 1.6x larger. An advantage when you want telephoto behaviour; a drawback when you want wide angles.

Let’s Be Clear: Unless otherwise mentioned, in this book, when we discuss lenses and what they do, we use the behaviour when that lens is mounted.

on a full frame camera, i.e. we describe the lens “as it would work on a full- frame camera”. So when I say a 50mm is standard lens, I mean it is a standard lens on a full frame camera (on a crop camera you would use a 35mm lens for the same effect).

“What type of lens should you buy?” The choice is up to you. Both full-frame and crop lenses have advantages and drawbacks. Only you can decide whether quality is most important to you, for instance, or money.

Either way, any modern DSLR will provide quality beyond that of good professional cameras even just a few years ago. This is a great time to be a photographer.

—

The article above is part of Michael’s “Mastering Your Camera” book, obtainable from http://learning.photography. You can get a full chapter preview from here.