In keeping with the “flash” tips, in anticipation of Saturday’s Advanced Flash course in Toronto, with Guest Star David Honl, for those of you who are trying wireless flash for the first time: here’s a beginner’s problem to avoid.

A picture of one of my favourite items (not) lit with an off-camera flash on my left using a Honl Photo Traveller 8 softbox; and a reflector on my left:

Can you see the problem? If you have eyes, you can: that horrible shadow.

You see, even though I used the off-camera flash with the Honl softbox, I failed (for the purposes of this demo, of course!) to disable the on-camera flash.

The on-camera flash (which can be the popup, on a Nikon or on a Canon 60D or 7D, or else an on-camera 580 EX or SB-900) is there to direct the off-camera flashes with “Morse code” pulses that happen before the shutter opens. So you need to make sure that when the actual flash happens, that on-camera flash is silent.

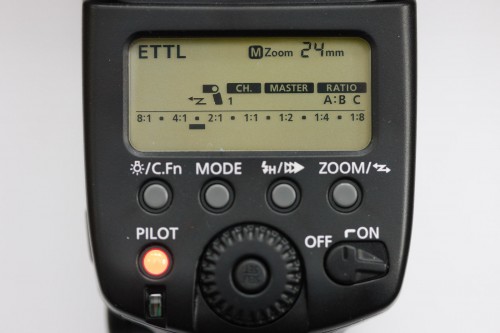

And you do that by setting the on-board flash to off. “–” on a Nikon, in the CLS menu, and just “disable” on a Canon. On the Canon, look, there are no rays coming from the flash head:

So then it still looks to you like it is working, but in fact it only fires its “Morse code” instructions, bu nothing else.

Now we have:

That’s better!

—–

One more recommendation, if I may (you will forgive me): there are spots open for the all-day “The Art of Photographing Nudes, 2 April 2011, Mono, Ontario. We use the same lighting techniques you are learning from me here, and more. Same model as last time, same two pros teaching! Click here to book.