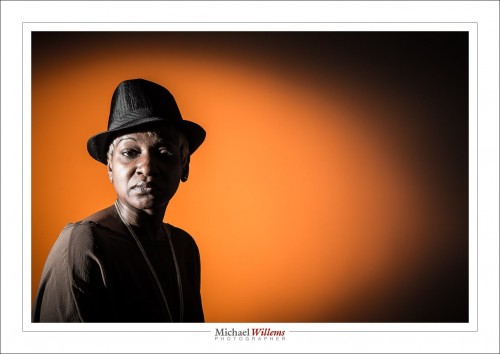

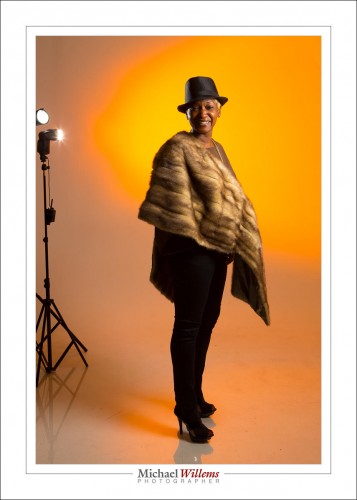

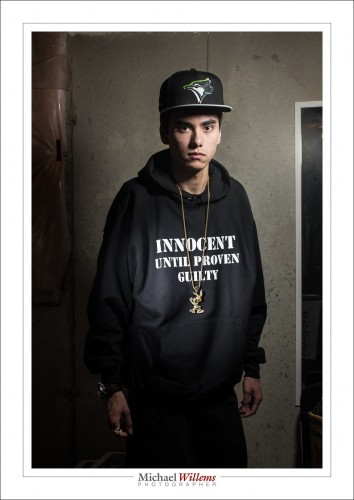

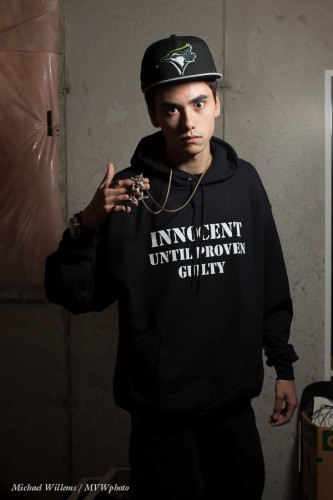

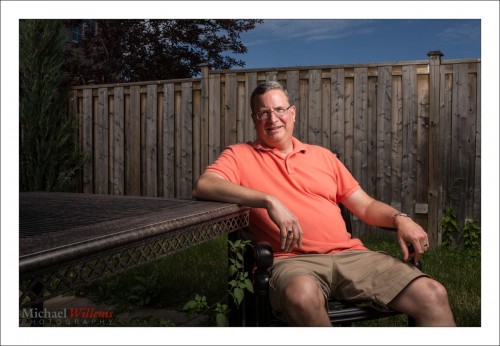

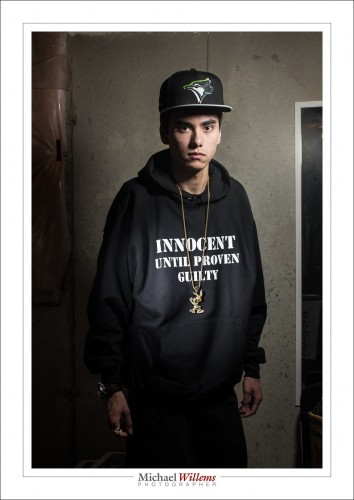

My younger son, who is a rapper, told me tonight, on his birthday, that he needed a new portrait for publicity for his new album. So I obliged, before cooking dinner and while simultaneously doing laundry. Here he is:

That image took maybe twenty minutes, half an hour tops – but a lot of experience and thinking and equipment goes into a portrait like that.

First, what is required? We discussed, and he clearly wanted a serious, dramatic, look. In a grungy setting. The T-shirt text and the bling should be clearly legible and visible, respectively. So OK – the briefing being clear, I used the basement studio, and freed just enough space to do a half body portrait.

Then the light. Speed was of the essence: I was about to make dinner. So I used speedlights. First, I set up a light stand with a 430EX flash set to manual, 1/4 power, and driven by a pocketwizard. I equipped it with a Honl photo 8″ softbox. I feathered the softbox to get the right amount of drama in the light, and to get Loop Lighting, almost Rembrandt Lighting, on his face.

The camera was a 1Dx with a 50mm f/1.2 lens, set to 1/125th sec, f/11, 100 ISO. I knew the 50 was perfect for a half body portrait in a small space.

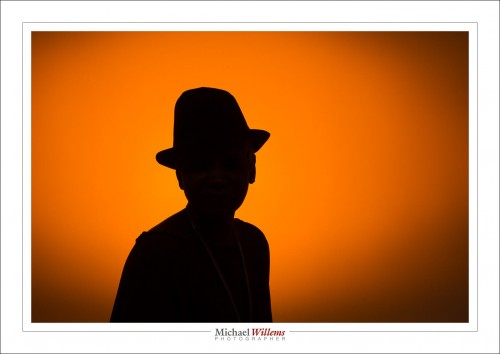

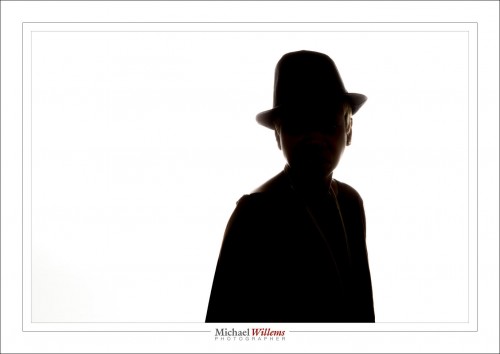

I tried, and the photos were OK:

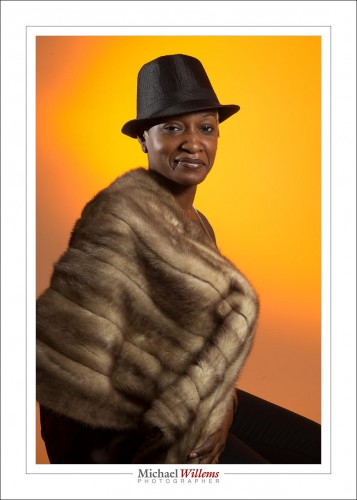

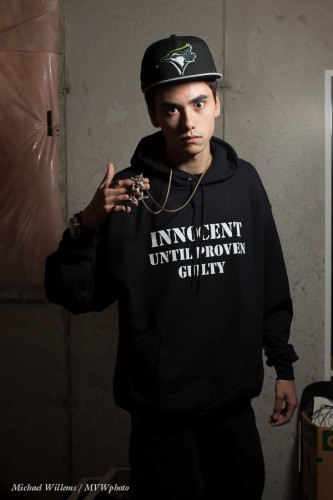

Not too bad, but we wanted a little more emphasis on the writing. And more texture of the shirt. And clearly visible bling. So I added a second speedlight, this time with a 1/8″ grid, for a tight line of light, and aimed that at the shirt. Also equipped with a pocketwizard, and set to lower power (1/16th). Not having had time to prepare, I took my time finding things like cables and a bracket that fit the flash – all part of the fun.

I set the lights to the camera’s desired settings of, if you recall, 1/125th sec, 100 ISO, f/11. I used a light meter to verify that.

And there you have it. A few pictures – I took a total of 30, and we chose his preferred one, the one at the top. I could have done the light thing, the vignetting, in post, but call me crazy: I call that cheating if I could have done it in camera.

As a result, almost nothing needed to be done in post, but that still takes time: selecting, removing the odd bit of dust, any perspective correction, and so on.

Total time taken, as said, less than half an hour including getting things ready, setting up lights, moving stuff, and the entire discussion and post work. But that’s only because I have done this before. Experience is important. The good news: you can gain experience too and it costs very little.

___

If you want to learn, and you live near Oakville, Ontario: evening Flash course on 3 Oct, and 5-evening course with a weekly evening lesson starting 2 Oct. – both these small courses have open places still.