Today, I would like to share another note on prime lenses. An oft-recurring theme here at Speedlighter.ca.

“Prime” lenses, as you know, are what we call non-adjustable lenses, i.e. non-zoom lenses. A zoom lens has varying focal length (e.g. “16-35mm” or “70-200mm”); a prime lens has just one focal length (e.g. “50mm”).

So remind me – why would I want prime lenses, again? Surely zoom is much more convenient?

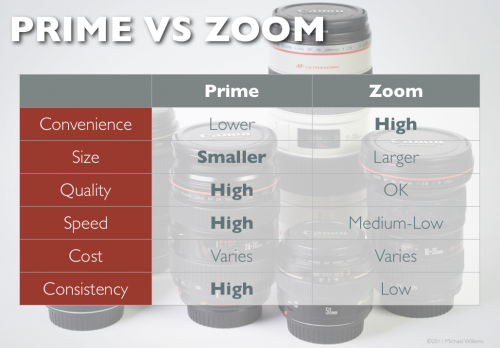

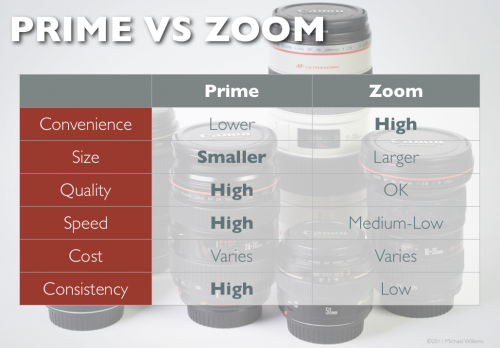

Yes. As I wrote before, a zoom lens is indeed more convenient. But it is not always better. In fact I shoot with primes as often as I can, for good reasons. Some of those reasons here:

A prime lens is often smaller and lighter, and almost always better quality. Primes are usually faster (they can go to a lower f-number, i.e. they have a larger aperture).

But two benefits are often neglected, and yet these are very important.

When you are learning, the prime lens teaches you the relationship between aperture and depth of field very well. You may recall from the post the other day that aperture, lens focal length and distance to subject all affect the depth of field in a picture. With a zoom lens, it is hard to get a handle on this, since you are changing one of those variables with every shot. With a prime, you really come to feel this relationship.

When you are shooting, a prime enforces consistence and discipline. Instead of every shot being different in look and feel from the last one, you get a “style” for the shoot. Your distance to the subject will be more consistent. Your settings for flash compensation and exposure are more consistent and hence, easier to handle.

And that is why I love to shoot with my three primes, whenever I can.

So yesterday, reader Leaman, responding to a previous post on this subject, asked:

Going through some of your older blogs and came across this post hoping to get some advice.

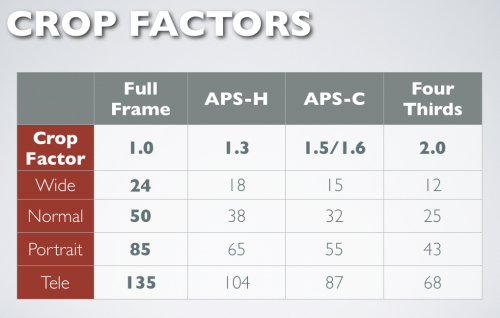

I have been thinking about getting a second lens for my Rebel series camera and am torn between primes and zooms. Specifically, I was looking at the EF-S 17-55 f.28 zoom vs getting both the 24mm f2.8 and 35mm f2.0 primes. I already own the 50mm f1.4.

Assuming that cost is not a factor, could you give me your thoughts? From my readings in your event photography shoots, you typically use a zoom as a walkaround and swap for a faster lens as needed.

Considering the 24 and 35 primes that I’m looking at are no faster/slightly faster than the zoom lens, would it make sense still to get the zoom lens? The only thing I think the zoom has in benefit over the primes is the versatility of less lens swapping. From reading my reviews (maybe you have your own reviews from experience as well) the build and picture quality between the 3 are not that far off from each other.

Well, first off, I would say that a whole stop faster, since you are talking about one f/2.0 lens, is more than just slightly. That stop can make all the difference, especially with side lenses where it can be tough to get selective depth of field. And for the 24mm lens, the other benefits still hold.

When shooting an event, I regularly use a zoom, true; but there are many situations where I do not. Low-light events, for example. And the 35mm prime lens is my favourite, for the reasons outlined above. But at the longer end, zoom is more important – so I often use 35mm prime plus 70-200mm zoom.

So Leaman, while indeed there is not one right or wrong answer, and it depends on what you shoot – but without knowing more, personally I would recommend the primes.