…non est disputandum. You can’t argue over taste.

As regular readers know, I like to shoot “in camera”, and keep post editing to a minimum. For the most part, my photos are basically SOOC: “Straight Out Of Camera”. But sometimes. I make exceptions.

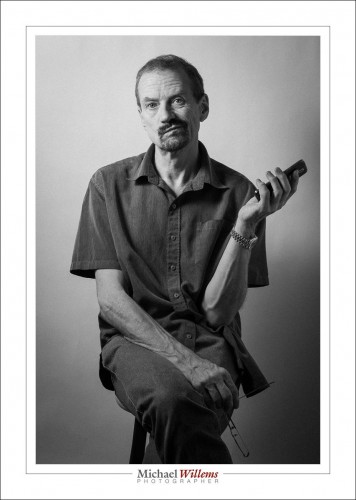

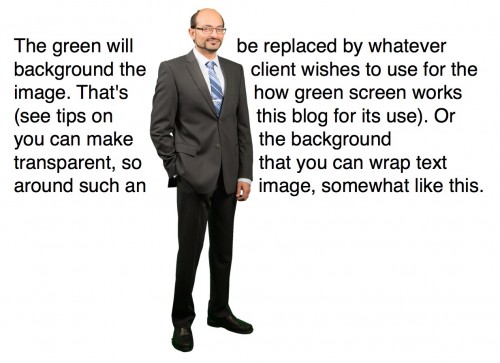

One is this style, a very bright, contrasty, cool, desaturated, sharp style that mostly loses everything into pure white, making eyes and other features stand out dramatically.

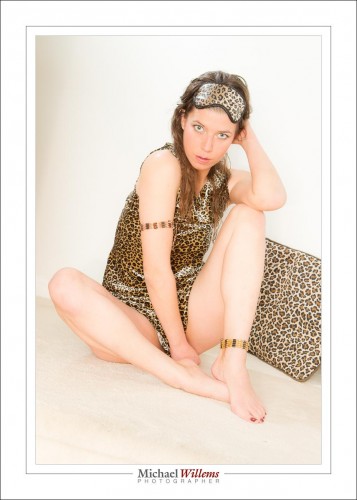

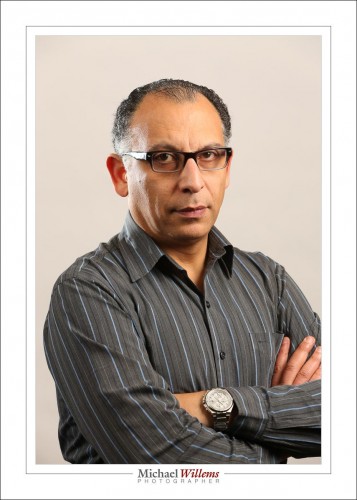

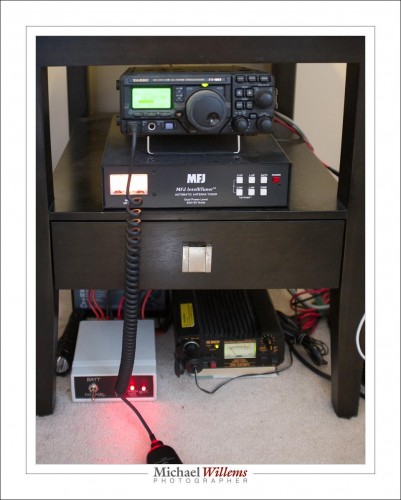

Here’s another example, before and after, so you can see what I did. Here’s the original, before the edit:

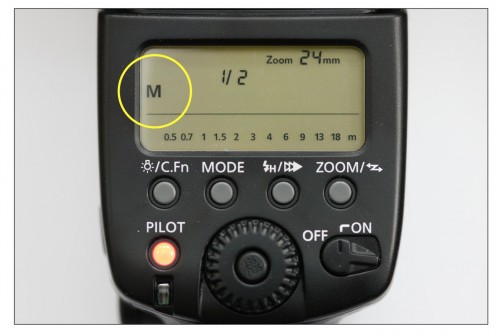

Shot at the following settings (press “i” in Lightroom repeatedly to cycle through the Information options):

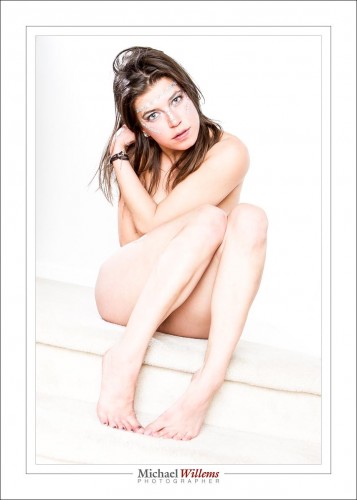

After the enhancement:

Note: the “before” picture was not bad. I strongly believe that you should use techniques like this to enhance, not to fix.

I like this so much that I made it a User Preset. After making your adjustments, click on the “+” in the Develop mode’s preset panel on the left.

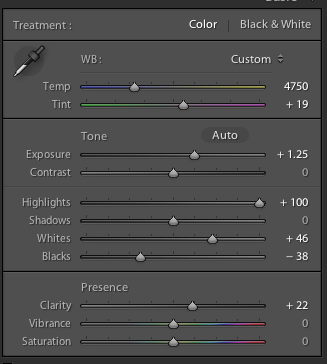

This preset consists of the following adjustments:

…in addition to which, I set “sharpening” (in the DETAIL panel) to +80 and “noise reduction” to +20.

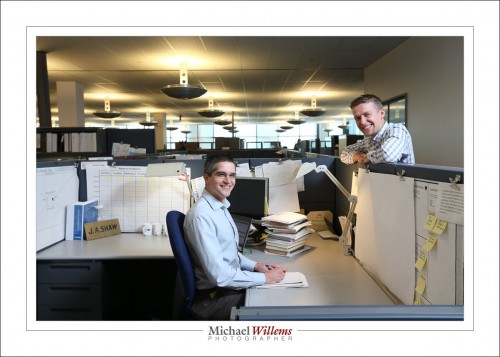

Here’s a side-by-side comparison of an image before and after:

I like that sharp look a lot.

Be careful not to overdo it and apply a particular “look” to all your work. Aim to do it in camera, and apply styles (via presets) only when needed, when they add something. As I believe this one certainly does.

___

BUT MICHAEL, I hear some of you say. “you are giving away your secrets”. Yes, I am. Because adjustments can be found anywhere. What cannot be easily copied is my artistic insight, people skills, $30,000 in equipment, and experience.

Would you like more secrets? Be my guest: have a look at the Christmas Specials on learning.photography: see http://learning.photography/blogs/news right now.