A friend just asked:

Hey Michael, How would you rate JPEG FINE vs RAW or TIFF? I am getting 8 meg JPG FINE file sizes and they are also OK to upload onto face book, go figure… I like the idea of RAW larger file sizes, even though they do require extra processing to use in Photo Shop. Is it worth it in the end?

Good question.

JPG fine and RAW are about the same quality, sure.

But JPG is the end result, while RAW is like a negative. RAW is better because:

- It has more colour bits (11 or 14 per colour, not 8 like the JPG). Meaning, more ability to fix, if you under- or over-expose or if the picture contains a high dynamic range.

- Settings are not yet applied, they are suggestions only. Setting like colour space, white balance, contrast, sharpening. In a JPG, what you see is what you get; in a RAW, you can roll back the settings.

Both reasons are showstoppers in some images.

So you can shoot JPG if you never make a mistake, and if you never need to change your mind on a setting like colour space or white balance. (Get the idea?)

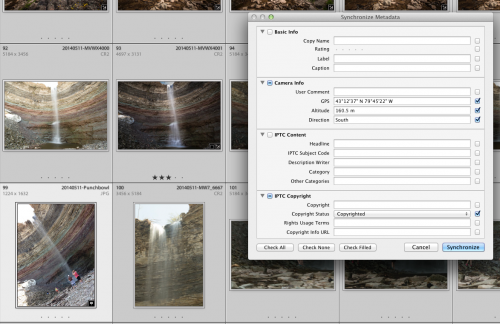

But extra work? In Lightroom, select all, then “save as JPG”. Two clicks of extra work–but you get the chance to edit before you do that, if you like.