Mass hysteria: we see it in humans all the time. Don’t use your cell phone in a gas station (total number of fires or explosions worldwide as a result of cell phones: zero). Don’t use your blackberry in a hospital (a 100 mW blackberry is supposedly a danger, while the doctor’s own blackberry, or the security guard’s 5,000 mW walkie-talkie, apparently represent no danger). Our local hospital has a No WiFi rule—and yet there is a WiFi network all over the hospital, named “staff only”.One presumes staff WiFi is kinder, gentler, somehow. Do not vaccinate (danger of vaccination: negligible. Danger of the diseases prevented by vaccination: immense). And so on. Superstitions are dumb, and I mean that: dumb because they knowingly do not look at evidence, just at emotional “I read it on the Internet” inputs.

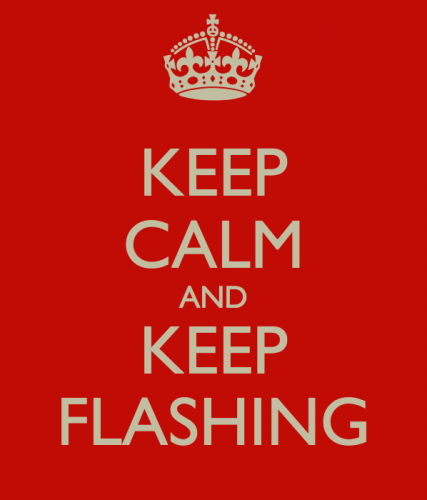

One particularly insidious one is the uniquely British “This Report Contains Flash Photography” warning, with an exclamation mark, no less:

Every news item in the UK that has a photographer flashing is preceded by this warning. Even news web sites carry it. Newsreaders say it. Enough to make you really, really fear flash photography. And as you may have guessed, The Speedlighter cannot let that go unchallenged. It is insidious because it leads to a general fear of flash.

The British justification is that there are some epileptics sensitive to flashes. Which is true, and we should not trivialize the seriousness of epilepsy. I would not: I myself have a brain that is very sensitive to light flashes at certain frequency, and EEGs have shown me to be very close to this type of photosensitive epilepsy: my brain displays distinct epileptiform EEG patterns. I remember the EEG: a weird experience, to have my brain affect the frequency of the flashes I was seeing. Brrr… Br-r-r-r-r-r… Brrrr… B-r-r-r-r-r-r… the flashes went.

However, (a) there are very, very few people with actual photosensitive epilepsy (a few thousand in the UK, The Guardian estimates; it is unlikely that out of those, more than a few are watching any particular broadcast), and (b) they are sensitive to repeated, regular flashes, say at 15-25 Hz, not to individual and irregular flashes from cameras.

The reason this warning is nevertheless carried is, apparently, a regulatory one. Safety above everything, and the law is the law.

And the problem with that is that if we put safety above everything, we do not have a workable society. Of course, in practice clearly we do not do this: we make reasonable accommodations. Else, cars would have to move at 5 km/h with a red flag preceding them. And with two drivers at all times, preferably. We would, of course, not fly airplanes at all; nor would we ride horses. All nuts and nut products would need to be permanently banned, as would alcohol and tobacco—and fat. We would force-vaccinate all kids. All movies that contain any adult situations, nudity, political statements, religious discussion should be banned for fear they may offend.

As you see from these hyperbolic hypotheticals, saying “safety above everything” is unworkable, and we do not do it. We just pretend to, because it is comfortable for simple minds to hear that our governments are removing all risks.

When deciding whether a warning is useful, you look at other places, Do other countries mandate this warning? Not to my knowledge; and yet, there are no hordes of Americans, Germans, Canadians, and so on all dropping like flies from flashes in news reports. So we can safely say: yes, this is another case of mass hysteria. If you are asked not to flash because someone objects, fine. If you yourself have light-sensitive epilepsy, then ask for no flashing. Other than that:

___

Have you seen my new Video With Your DSLR course on the schedule? Check out www.cameratraining.ca‘s schedule page.