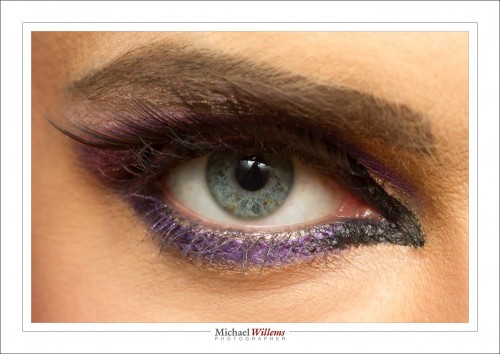

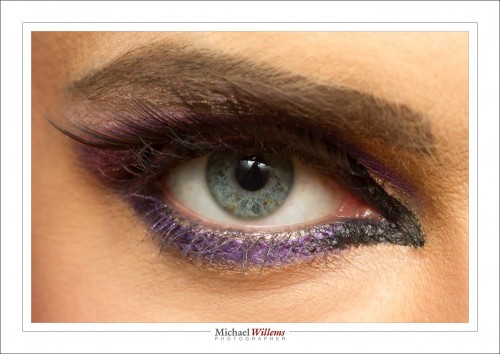

To shoot a true macro picture, you need a macro lens (Nikon calls this a “micro” lens). This is a lens that allows you to focus close-up. Like this from yesterday’s shoot, a shot for the make-up artists to detail their work:

When you click and see it full size, you will see how ridiculously sharp this is: “DNA-level”, as I like to call it.

So why and when do I take a shot like that?

I do macro shots:

- When I want to have some fun. Macro can be done in your kitchen all year round: when you make small objects large, they take on an entirely different life of their own.

- When needed to document things—like the make-up job above.

- When shooting small objects, like jewellery.

- To get detail of an object, detail I cannot

- When I think I may want to get close, even if I may not need to, I still like to use the macro lens so I have the option.

Shooting macro means you are close… and this in turn means that your depth of field is extremely restricted. You will probably need to shoot at f/8, f/11, f/16 or worse. You may even have to take multiple shots with varying focus distances and put them together electronically. A very close shot at f/2.8 has a depth of field (“where it is sharp”) of fractions of millimeters.

One mantra one often hears is that a tripod is necessary. Yes, it is recommended, and sometimes it is necessary, but with good shooting technique, you can often do without it too. Like in the shot above. 100mm lens on a Canon 7D camera; set to manual at f/11, 400 ISO, 1/125th sec.

Finally, the light. I used a bounced flash and I ensured that only the flash shows (by using “fast shutter, low ISO, high F-number”). Using only flash ensures that you see no motion blur: a flash happens in about 1/100th second (or even faster at lower power settings), so it’s like using a fast shutter speed.