If anything, my mantra has always been: “keep it simple” – reduce everything to the essence and you have a much better product. I am big on this in business, in photographic composition, in presentations; in teaching; in writing (do it in half the words!). In just about everything. Simple is good.

Including in computers, and that is why I use a Mac, and that is also why the book I just read, “Insanely Simple” by Ken Segall, struck such a chord. Get this book – Ken is an advertiser who worked with Steve Jobs for many years and relates his view on why Apple is great very succinctly (and, I think, gets it right: one word: “Simplicity”). Another example: go choose a laptop at Apple.com. Go do it, Right now. Ah, you’re back after a minute? Good. Now go choose one at Dell.com. Good luck, and see you in a few weeks.

Such a relief to read this. I have been saying this for decades: a great consultant makes complicated things simple; a not-so-good consultant makes simple things complicated. Steve Jobs understood this like no other. Cell phones were brain dead.. he made one that wasn’t. It’s not as though I and many others had not been saying that for years – we just did not have the power to change things. I used to curse at my Blackberry’s stupidity – designed by people who apparently took delight in making things complicated. They took the easy way out.

You see, simple is difficult to do, and difficult is simple to achieve. It is easy to make a bad phone, hard to make it simple and intuitive. Be lazy – let the client do the work! Like the makers of TVs today. I, and the four remotes on my table, do hope Apple breaks apart that market, too, and very soon.

In photography, it’s the same. Simple means thinking “how can I reduce this photo to its essence”?

Perhaps by using a long lens with a wide aperture, to make the background blurry:

Or by tilting up to keep things out of the picture, as in this 15-second exposure:

Or by angling to keeping a landscape simple, as in this image made near Drumbo, Ontario:

Or by cropping to make things simple:

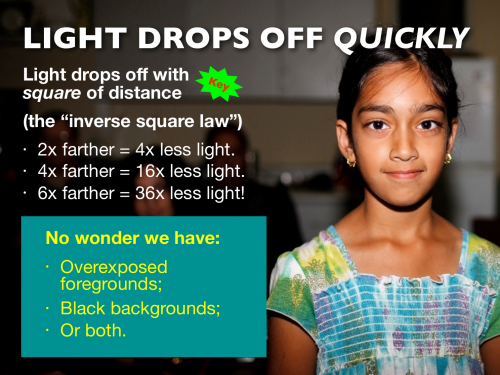

or by using simple light – my favourite outdoors light by far is a single umbrella with an off-camera flash, sometimes with a second flash to be the hairlight (although I prefer to use the sun for that, from behind). Here’s a two flash setup:

Which gives us:

Or by leaving out light:

Sometimes I fail, like in this image where I inexplicably did not trim off the leaves on the left:

But when this “light from one flash” works well, which it usually does, it works very well:

So my message is: go the extra mile to simplify your images. However you do it, simplifying is a way to reduce an image to its essence; to get clarity in your work.

Simple minds think that simple is bad. Sophisticated minds know that simple is good.

POSTSCRIPT – ADDED:

Let me illustrate… this is how dumb TV systems are. To turn on my TV, I need to:

1. Aim remote at cable box

2. Press “cable” on remote

3. Press POWER

4. Aim at TV

5. Press “TV” on remote

6. Press POWER

4. Aim at audio amp

5. Press “Audio” on remote

6. Press POWER

7. Press “Cable”

8. Adjust volume and choose channel

9. Put down remote

10. Grab Apple remote

11. Aim at Apple TV

12. Press MENU

13. if Apple tv is to be watched:

a) grab remote

b) press TV

c) press INPUT

d) select APPLE TV

e) grab Apple remote

d) select program

I cannot imagine why we allow this nonsense. APPLE, WHERE ARE YOU!