A reader wrote to me today about pro equipment, and about how pro cameras seem to be necessary for the work I describe in some of my posts — it would be better, he suggests, if all posts were accessible to all people, amateurs and pros alike.

Now, if this reader had said “pro-quality lenses“, or at least “fast lenses“, he would have had a point. But while sometimes I do use the features only a professional-grade camera has, this is in fact rare. Or rather, for this to have an effect on the quality of the photos is rare. A modern camera, yes, sure; but a pro camera is rarely needed.

First, what is a pro camera? I would define it as a camera body, often large, that costs $3,000 or more, without the lens. Cameras like the Canon 5D MkIII or 1Dx.

And what do these Pro cameras do more than a “regular” camera?

Actually, very little. You see, all cameras from the same generation are similar.

Let’s have a look at a few of the typical things that a “Pro camera” does more than an entry level camera:

- Larger, brighter viewfinder

- Stronger, “built like a tank”

- Longer battery life

- Better weatherproofing

- Faster continuous shooting

- More personalization options

- Better focus systems

- Better and faster internal photo processor

- The ability to write to two memory cards at once

- More options

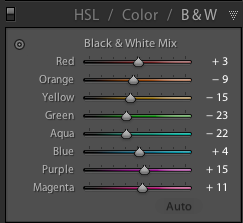

- Sometimes, lower noise at higher ISOs

But there are also things a pro camera does not do:

- No “scene modes”

- Often, not even a pop-up flash

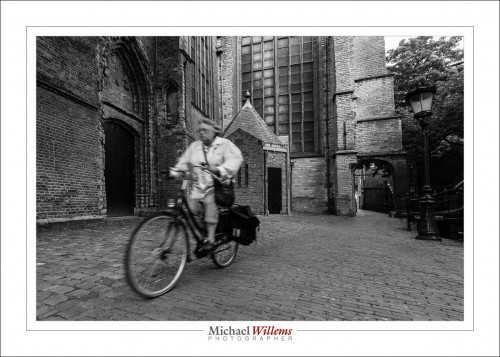

Big benefits, yes, but what of the above is important to the actual photos you take? Other than the “higher ISO’s”, not all that much, really! And that ISO point is misleading: it is more the difference in generations than the difference in “type of camera” that defines noise performance. A modern entry-level camera, for instance, can often do much better than a five-year old pro camera. Sure, my 1Dx goes to obscenely high ISO values, but take, say, a Nikon D800 and sample it down from its crazy number of megapixels to the number that I have, and you get very comparable performance. This is why we upgrade every few years: better image quality.

So if you have a modern camera, you can do what I do – all of it, or almost all of it.

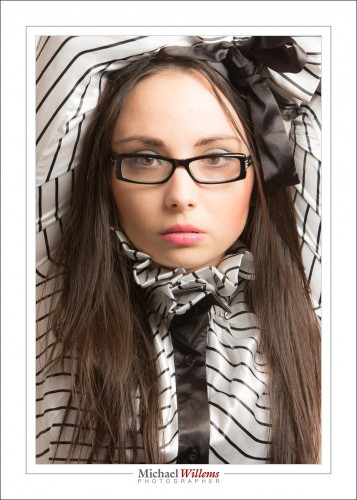

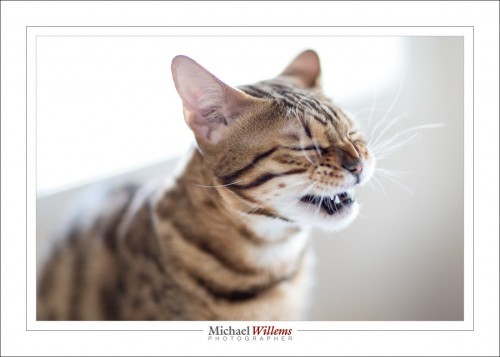

So what is important to image quality? I would say (a) how new your camera is, (b) its sensor size (full frame is good) and (c) the lenses. Lenses make a very material difference to your images. Good lenses are more sharp. They have better colour performance and less of the various distortions. They allow more light to enter the camera (faster lenses, i.e. lenses with lower minimum “f-numbers” ), hence allowing more blurred backgrounds, and the ability to use either faster shutter speed or lower ISO settings in the same light.

So while no doubt I do the occasional post that really needs a Canon 1Dx, mostly it’s just convenience and practical all-day use, but not the quality of the photos, that is affected by the camera; while lenses almost always affect the photo. So if you have money, I would recommend two things:

First, ensure you have a modern camera, preferably full frame. It does not need to be a pro camera, but they get better every year, so “modern” means good performance at high ISO values.

Then, ensure that you have the right range of fast lenses, including a few prime lenses.

And then go have fun!