One light can be enough.

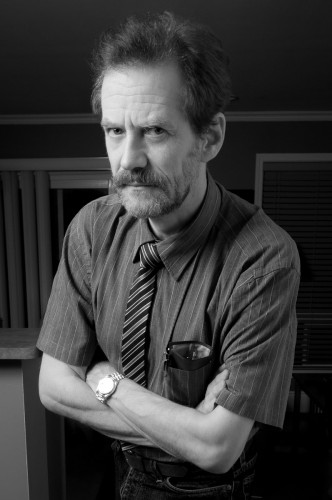

Look at this great image. How was it made?

The answer is: one flash. Yes, that is all.

In this case it was a strobe, fired through an umbrella. But it could have been a speedlight.

The difference between those two options:

- On a strobe, I measure the light with a light meter, and set my settings on the light and on the camera accordingly. And they are set for the entire shoot. So whatever the subject, the settings are the same. Done!

- If I am using speedlights, however, the camera meters every shot. And it meters it by measuring light reflected off the subject. So the subject matters. A dark subject will fool the camera into overexposing, so you need to use negative exposure compensation. A very bright subject, the opposite – you will need positive exposure compensation.

Those are very essential differences. Read the above until you understand it, or ask me if you do not.

They have consequences:

- If the subject distance will be static, use strobes/manual. If, however, the distance changes, then you should use TTL.

- If the subject brightness changes from shot to shot, use strobes/manual. If, however, the subject brightness is the same between shots, TTL may be useable.

Confused yet? It is really very simple, once you know it. But then, the same applies to brain surgery.