…as in colour. Today:

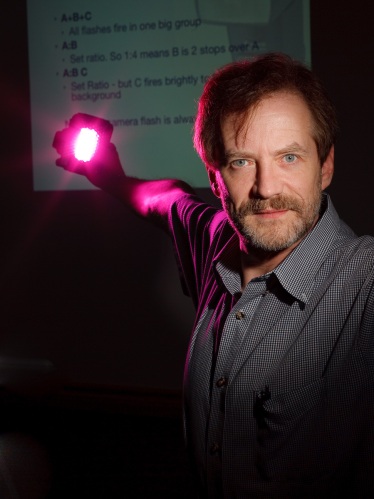

I took this picture yesterday and it shows a few things:

- Lower the background’s brightness = increase its saturation

- To add excitement, add a splash of colour!

- In particular, add red to the green and blue you find in nature

- Dramatic lighting = contrasty lighting

Five speedlites were used in the production of this picture. Four on the sides and one behind me. they were fired via pocketwizards.

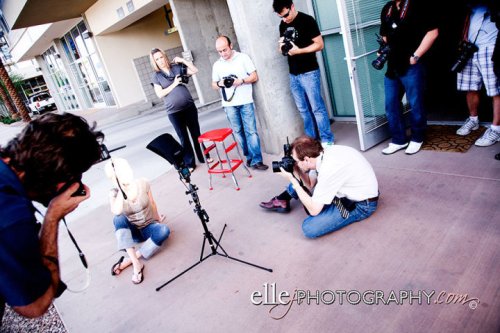

In any shoot, the worst thing a photographer can encounter is bright light.

Why?

Here’s why. Think along.

- The available (ambient) light will be fill light.

- That, and the fact we want these saturated colours, means it will have to be darker (say, two stops darker) than the main, flash light.

- That means the flash light has to overpower it (by, say, two stops).

- That means the flash has to be two stops brighter than the sun.

That’s why we call this “nuking the sun”.

For which we needed five flashes, four on the sides and one behind the camera. Firing at full power, mostly.

(That much because ambient is controlled by ISO, aperture, and shutter speed. Shutter speed cannot go beyond 1/200th second (or whatever your synch speed is). ISO is low already. So aperture is the only way to affect the background. But Aperture also affects flash exposure so for each stop you close the aperture you need to double flash power.)