You will have heard talk of “crop cameras” and “full frame cameras”. But perhaps the fine points are not exactly clear to you. Let me try to illuminate the subject a little.

First, the definitions. A “full-frame camera” is a camera whose sensor is the same size as a 35mm negative used to be. A “crop camera” is a camera whose sensor is smaller (usually 1.5x, 1.6x or 2x smaller).

Full frame cameras are generally more expensive: they include such cameras as the Nikon D800, Nikon D4, Canon 6D, and Canon 5D Mark III. Generally speaking, “bigger is better”: full frame cameras have some major advantages over “crop” cameras—but the reverse can also be true.

Available Sensor Sizes

- Lower-end (and many higher-end!) point-and-shoot cameras usually have very small sensors. These do not make it easy to get blurry backgrounds, and they generate a lot of noise at relatively low ISOs.

- Next, there is the “Micro four thirds” format—these sensors are almost as big as a crop camera’s sensor. Micro four third cameras are twice as small as a negative.

- The next step up is the “APS-C” crop sensor – 1.6 times smaller than a negative for Canon; 1.5 times for a Nikon. Most DSLRs have this size sensor. Some quality small cameras also do (like my Fuji X100).

- Next, there is a Canon-only size that is 1.3 smaller than a negative—this is the format used by the 1D (not 1Ds or 1Dx).

- And finally, there is the full-frame sensor—it is exactly the size of a 35mm negative.

Should you save up for a full-frame camera? Maybe. Maybe not. As so often, it depends.

Pros and Cons of “Full frame” and “Crop”.

Full-frame sensors have several advantages over smaller sensors:

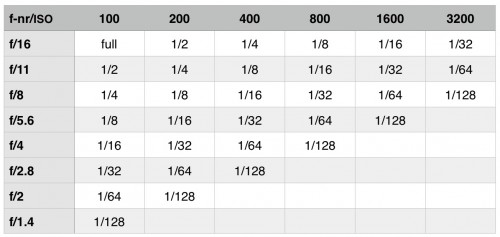

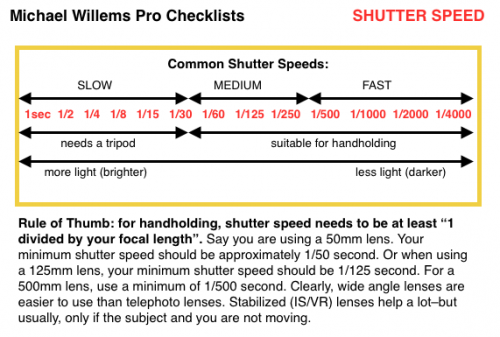

- Full frame sensors generate lower noise (i.e. produce better quality photos) than crop sensors of the same generation and with the same number of megapixels (Mp). This means that, again given equally old cameras with the same number of megapixels, they are better at high ISO values, where noise can become a problem, than crop sensors.

- The viewfinder on a full frame camera is larger and brighter than that on a crop camera.

- In the same conditions, you can achieve blurrier backgrounds than with a crop camera.

- Wide-angle lenses actually work as wide-angle lenses on a full-frame camera (as opposed to on a crop camera, where each lens works as though it were longer, compared to using the same lens on a full frame camera).

- The entire lens is used. Crop cameras use only a smaller portion of the lens, so imperfections in the glass can, at least in theory, become more significant.

That’s a nice list, and it explains why most pros use full frame cameras, but there are also advantages to using slightly smaller sensors:

- They cost less.

- They are smaller, so cameras with a crop sensor can be slightly smaller.

- They can use special lenses (DX lenses for Nikon, EF-S lenses for Canon, etc) that were made especially for smaller crop sensors; these lenses are therefore smaller too, so they cost less and weigh less.

- And last but not least, a big one: lenses “appear to be longer” by the crop factor compared to the same lenses used on full frame cameras. This is an enormous advantage if you need a long lens, such as when shooting lions in Africa: your 200mm lens will now work like a 300mm (Nikon) or 320mm (Canon) lens. And if you have looked at the price of long, fast lenses recently, you will know how big this advantage can be.

Drawback of special “crop only” lenses (DX on Nikon / EF-S on Canon) : if you upgrade to full-frame, you need to replace these lenses. My strategy is to only buy “normal” lenses, those that can be used on any camera (i.e. “EF” lenses, in the Canon world).

Misconceptions

I have heard and read many misconceptions. Misconceptions such as “full frame cameras have better colour”, or “full frame images can be edited more”. Those ideas are wrong. True, many crop cameras produce more noise at a given ISO than a full frame camera, but that does not mean that “full frame colours are better”. Also, age matters (any new camera is better than any old camera), and pixels matter (an 18 Megapixel crop camera probably produces less noise at a given ISO than an equally old 33Mp full frame camera). So a blanket statement like “full frame images can be edited more” is a half truth at best.

Effect on Apparent Lens Length

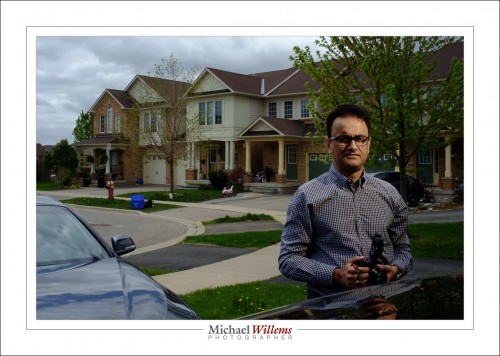

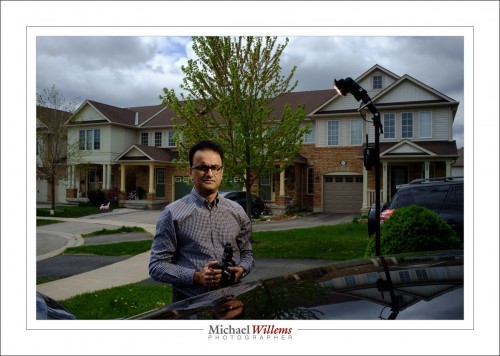

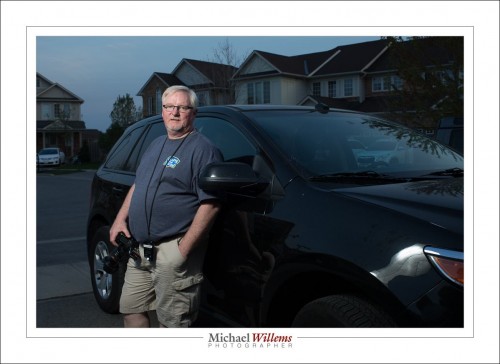

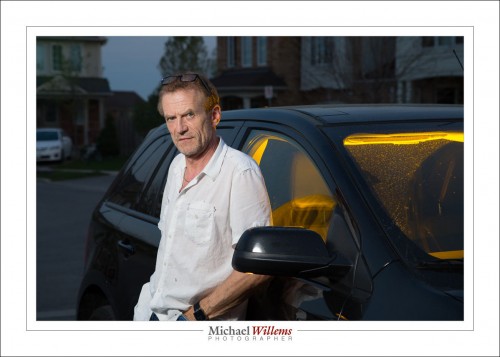

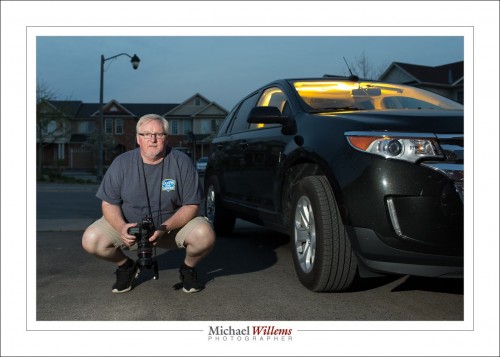

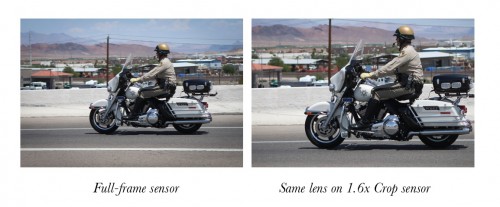

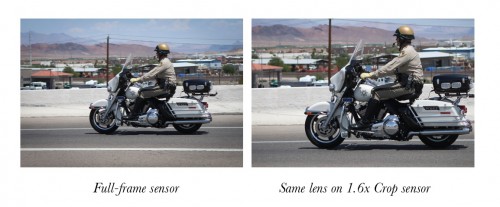

As said, crop cameras “appear to lengthen a lens”. That is, a 35mm lens works like a 50mm lens when used on a crop camera; a 50mm lens works like an 80mm lens when used on a crop camera; a 200mm lens works like a 300mm lens when used on a crop camera, and so on. (All numbers approximate). The same lens, for instance, mounted on two cameras with the same number of megapixels, one with a full-frame sensor and one with a crop sensor, might give these two images:

In this example, on the 1.6x crop sensor (the sensor that is 1.6x smaller than full frame), the same objects in the resulting image would be 1.6x larger. An advantage when you want telephoto behaviour; a drawback when you want wide angles.

“What type of camera should you buy?” The choice is up to you. Both full- frame and crop cameras have advantages and drawbacks. If you were to summarise it in just a few words, you might say “full frame usually gives better quality; crop usually gives better value”. I usually prefer full frame cameras because of the better high-ISO performance at the same pixel count and because of the blurrier backgrounds; but I own a crop camera as well, because i like the fact that without buying more lenses, I now have more focal lengths available. After all, depending on the camera it is on, each lens now has two focal lengths, effectively.

Only you can decide whether quality is most important to you, for instance, or money. “What camera should I buy” is like asking “What car should I drive”. A tough question for anyone but yourself to answer.

Either way, any modern DSLR will provide quality beyond that of good professional cameras even just a few years ago. This is a great time to be a photographer.