No, I am not referring to people who enjoy opening their raincoat outdoors to show that they are wearing nothing underneath. As the Speedlighter, I am of course once again referring to flash lighting.

On a pro photographers’ forum recently, a few people said they shot “with available light only”. They seemed proud of it.

I have heard this many times. And I admire people who can do this. But I must admit that whenever I hear it, I think “this is probably because the person in question does not know flash”. And in most cases, that is true.

I know, there are legitimate differences in artistic insights. And yes, you can make great art without flash. No dispute there. But that said:

- The number of situations you can handle is very much restricted if you do not use flash as an option.

- The number of styles you can produce is very much restricted if you do not use flash as an option.

Situations include very dark rooms. Back light. Bad colour. High contrast light. Badly directed light. Uneven lighting. Direct sunlight without squinting. Special effects requiring extra light. Special effects requiring colour. The list goes on.

And styles, even more so.

An example. Lucy and Matt’s wedding last year. Here’s me, about to shoot a group shot in direct sunlight:

\

\

(Notice how I am up? That is the only way to get all these people into the shot, if there are many layers of people.)

Anyway, if you zoom in (click until you see “original size”, you will see the people are not that well lit – not, that is, in a flattering way. And “bright pixels are sharp pixels” (Willems’s Dictum) – here, the people are not the bright pixels!

But in my shots, they are:

See what I mean?

And take student Melissa at last year’s Niagara School of Imaging at Brock University. No way you could do this type of dramatic portrait without flash:

Obviously, the effect photo from the other day cannot be done without flash either:

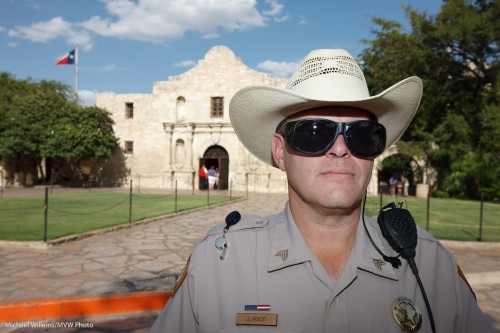

Nor can this:

Or this:

And the list goes on. Like this outdoors fashion shot of Melony and daughter Vanessa:

Which was shot like this, of course:

This, too, needs flash:

The list goes on. I think perhaps over half my images could not be made without flash. So.. why would you want to be a photographer who deliberately restricts herself or himself to half the possibilities?

___

Don’t forget, my new eBook is out: A unique book with 52 photographic “recipes” to help you get started immediately in many situations – including many that need flash. Read all about it here and order online today:

www.speedlighter.ca/photography-cookbook/