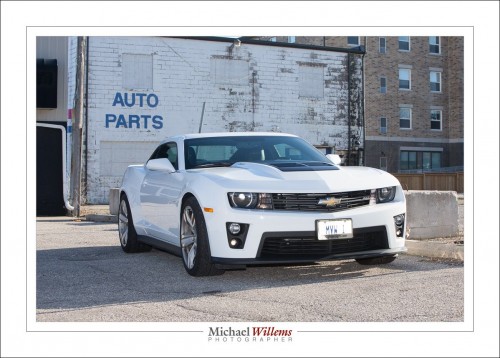

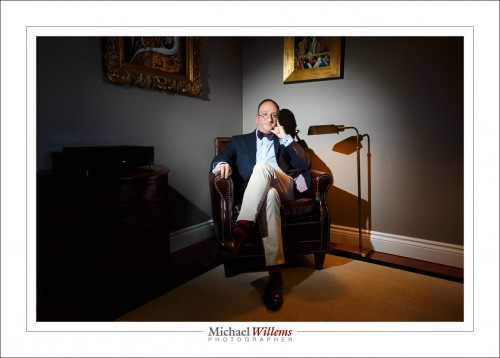

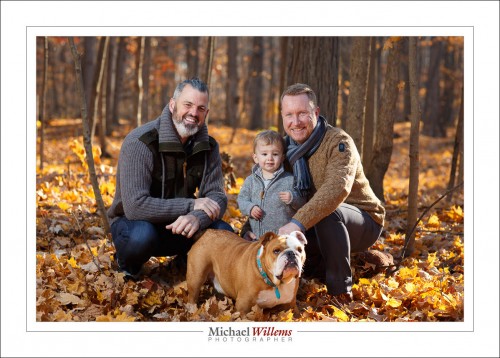

Sometimes, you will experience lens flare, a lowering of contrast due to incoming bright light. Like here, from a recent event:

You can’t do much about this: it will happen especially with longer lenses and lenses prone to it.

What you can do is minimise it and its effects. Here’s how:

- Remove any protection filter that your lens has on it. These make flare worse.

- Ensure that the lens is totally clean.

- Use the lens hood your lens came with.

- In addition, shield your lens from incoming backlight with your hand if you can.

- Position yourself so as to minimise incoming backlight. As you can see in the photo, this is not always possible.

- Avoid overexposing.

- In Lightroom afterward, use “remove chromatic aberration” in the lens correction section of the Develop module.

If you follow those tips, you have done all you can!

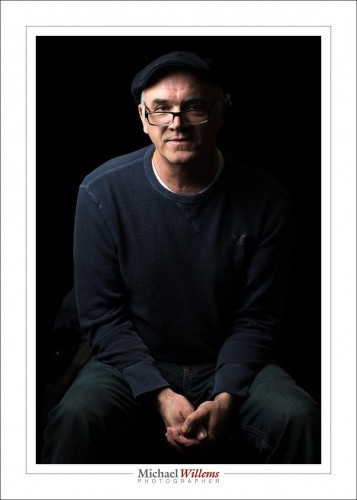

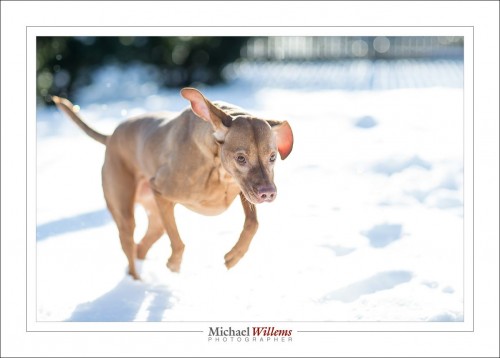

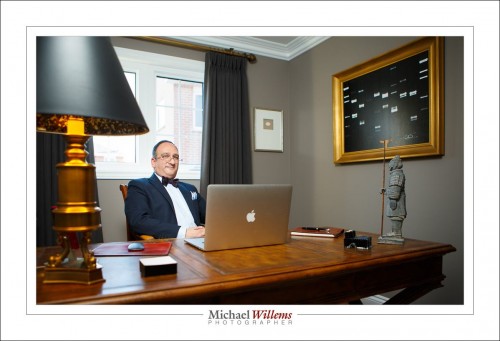

SPECIAL–SPECIAL–SPECIAL! … I have a very special opportunity for you:

Have you always wanted to be able to shoot pro images? Well… a short course can get you to an amazingly professional level. And for just one week, all personalized individual or group training, at your location or at mine, or via the Internet using Google Hangouts, is $60 per hour instead of $100 per hour – that’s 40% off!

This offer is valid only until 4 May, but you can prepay now for later training. Take advantage if this opportunity and kick start your craft: Contact me today to book.